Written by: Kavya Padmanabhan

Karate is more than just a fast paced stadium game. Instead, according to freshman Luma Hamade, it requires patience and strength.

Hamade had been practicing karate for four years at Prodigy Martial Arts in Los Altos. She is a brown second belt, one test away from a brown first belt and two tests away from a black belt.

Hamade became interested in the sport because her brother, senior Nabil Hamade, practices it himself. “I started because my brother was doing it and it looked like a lot of fun,” she said. According to Luma Hamade, Nabil Hamade has ceased to continue with karate after gaining his black belt. Growing up with a brother in karate has made Luma Hamade strive to continue with the sport. “It motivates me to go all the way to the end and not quit until I’ve reached my goal,” she said.

Hamade’s love for karate stems from many reasons. According to Hamade, it is useful because it is a great workout and always a good time. “I think the best part is the workout you get,” she said. “You become

physically stronger and you get more endurance.”

Hamade’s coach Raul Fabela has known Hamade since a young age. “I have seen her have a good time laughing with her training partners, and then when it comes time to spar, she goes at it while staying focused,” Fabela said. Fabela’s admiration

for Hamade’s commitment has only grown stronger. “The fact that she has continued with her training, even when she feels frustrated is something that I admire,” Fabela said. “This is a journey that many begin, but not everyone finishes.”

A typical practice varies for Hamade. During a private lesson, she will spend more time perfecting her form, while in kickboxing she practices drilling and punching. According to Hamade, steady commitment is a requirement in order to get a black belt. “There’s a lot of stuff you have to remember because you need to learn a lot of techniques for your black belt,” she said. “But it’s worth it.”

Although she does not plan to do it in college, Hamade is thinking about doing the sport later in life because it has changed her throughout the years. “It’s made me stronger and I’ve made new friends,” she said. “I’m less afraid of stuff too.”

Written by: Katherine Zu

Taekwondo started out as a hobby but soon grew into a serious commitment for freshman Maila Kuelker. Ranked nationally since the age of 10, Kuelker won the U.S. Open for taekwondo in 2009.

Kuelker took taekwondo classes and learned the basics at the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) on her seventh birthday as a birthday gift. “It was something I wanted to learn, but my parents only wanted it to be an afternoon activity,” Kuelker

said. However, the sport became more serious when Kuelker switched taekwondo schools a year later and started entering competitions. Kuelker wanted to do taekwondo for various reasons. “I just thought that it would be really diffe

rent, and I wanted to learn how to prepare myself if I ever needed to,” Kuelker said. Although she initially began the sport with self-defense in mind, she hasn’t had to use it so far. “I’ve never had to fight anyone, but it definitely played a part in others not wanting to mess with me, which I think has been beneficial,” Kuelker said.

One of the most challenging aspects of the sport for Kuelker is concentration. “The hardest things are discipline and trying to stay motivated, because there are a lot of times where you can just get bored,” Kuelker said. “It’s a lot of repetition, a lot of drills and mostly just fighting all the other teammates and helping them.” The weeks before the competition season, Kuelker trains four to seven hours a day.

The discipline she learns from taekwondo translates into the other sports that Kuelker plays, including the junior varsity basketball team. She also trains in other martial arts like jiu jitsu and mixed martial arts. “It’s really played a part in building a high stamina

and just strength-wise,” Kuelker said. “It’s helped me discipline myself so I’m not slacking and I can stay focused.”

The time and effort she put into taekwondo has paid off through the friendships she has formed. “Becoming a family with all these people on the team, but ultimately just improving, getting results, and winning makes it really enjoyable,” Kuelker said. “I think it’s a great feeling to wear a gold medal around your neck, and have all the experience you can get.”

In the future, Kuelker plans to continue improving and achieving a few goals that she has in mind. “I hope that I could get another chance to make the U.S. team, travel for competition, and maybe even make it to the Olympic games one day,” Kuelker said.

Written by: Catalina Zhao

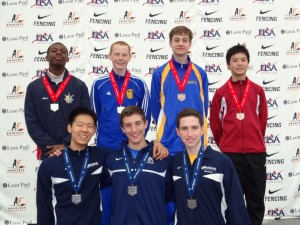

His nimble feet dazzle the audience with complicated footwork, as his mind calculates his next move. He lunges and his saber flashes. The crowd roars as he snatches another win.

Freshman Samuel Kwong is a nationally ranked saber fencer. He is number one in the men’s youth-14 age group and second in under-17. Of the three types of fencing, saber centers largely on agility. “Saber is a lot quicker paced, and you have to be very good at sprinting and capable of taking big

boosts of energy,” Kwong said.

After starting the sport at the age of seven as a result of his love for sword-fighting, Kwong eventually competed at national tournaments, the first of which he won when he was thirteen.

Kwong was recently awarded the gold medal in the youth-14 category at the North American Cup, held from Mar. 15 to 18. In February at the Junior Olympics, Kwong won bronze in the under-17 category. Last fall, Kwong competed at his first international tournament, the European Cadet World Cup, in Poland, also in the under-17 age group. Twenty fencers were selected to represent the United States, of which Kwong was the youngest. There, Kwong received the bronze medal. “At the World Cup, I

just tried to make good use of it,” he said. “That day, I was in a really good mood, and everything went according to what I wanted. I fought hard and I got results.”

Kwong fences at the Cardinal Fencing Club at Stanford University under the tutelage of Olympic gold-medalist George Pogosov. “Samuel deserves the best words and praises as student,” Pogosov wrote in an email. “He is willing to work for hours to learn all coach’s tasks.”

Three times a week at the fencing gym, Kwong practices footwork, does regular bouting and has private lessons with his coach. On the other days, he cross-trains at home. “Samuel trains a lot and he works very hard,” freshman Kenny Chui said. “[Fencing at Samuel’s level] is very tough and you have to work very hard to be able to do that.”

The aspects of fencing that attract Kwong are that it

is quick-paced, intense and less mainstream. “Fencing is like physical chess,” Kwong said. “You’ve got to plan ahead, and be a step ahead of your opponent. It’s 50 percent mind game, 50 percent physical game. There’s a lot of techniques and tricks you’ve got to learn to set up your game.” Kwong finds the hardest part to be maintaining the balance between the physical and mental parts. Kwong’s role models, such as his coach, push him to work harder. In addition, he looks up to his teammates, especially the ones older than him. “The way they persevere and the way they’re always ready are very inspiring,” Kwong said.

Fencing has greatly shap

ed Kwong’s charact

er. “The most useful thing I’ve learned is that you always have to have a fire in your heart,” he said. “When your opponent is in front of you, you have to be 100 percent ready.”

Kwong hopes to fence in college

and the Olympic Games. “Samuel is very perspective fencer,” Pogosov wrote. “He should get into Cadets’ National Team next year and our goal is National Olympic Team 2020.”

Whenever he fences in a bout, Kwong always tells himself to focus and have fun. “I tell myself to enjoy the moment,” Kwong said. “Focus on the moment.”