Written by Lindsay Maggioncalda

When my mom said I couldn’t leave the house after midnight on a school night, I’d go anyway. Several of my best friends were suicidal, and I would always come when they said they needed me—no matter what. Being there for them took priority over everything else in my life, not only because I loved them dearly and was genuinely terrified of losing them, but also because I found a formerly elusive sense of purpose in being a source of support for them. I idealized myself as some sort of guardian angel, and I distracted myself from my own inexplicable feelings of emptiness and hopelessness by attempting to help others with theirs

In the winter of my junior year of high school, when it seemed impossible for the situation to get any more dire, a friend I wasn’t even worried about took his life. Like a detonated bomb, the announcement of his death sent shockwaves through the community, devastating friends and strangers alike. It was taxing to support my friends before his suicide, but the aftershock felt like a fight for survival. Death felt so close it was almost palpable; each day I woke up fear stricken that it would happen again and another life would be lost. Desperate to keep my friends safe, I sacrificed sleep and invested all of my energy into frequent late-night visits and long conversations, cards, texts, calls, and hugs. I was tormented by my friend’s death and completely drained of all vitality, but I was adamant that I was fine, even though I’d been struggling long before his death. My motto was “grind through,” and every remaining moment of junior year was focused on doing just that?—?surviving until the next day and dragging my friends along with me. We just had to make it to the weekend, to the next break, to summer; then, we could recover.

Junior year finally ended, but things didn’t get better. I was crushed by the exhaustion that ensued when I completely neglected self-care, and the sadness and grief I’d always forcefully pushed away choked me into surrender. When senior year rolled around, I could barely get out of bed. I was “sick” often, and the silence that followed my recurring absences convinced me that I mattered to others only when I was laughing and happy. I was certain that everyone could see I was suffering but chose to avoid getting involved in my drama, and I doubted the sincerity of good-intentioned but vague offers to “talk about it.” After unimpressive initial experiences, I dismissed talk therapy as a waste of money and time, and antidepressants as ineffective drugs that served only to nauseate me during math class. Though I was aware of the history of mental illness in my family, I attributed my constant sadness to an inability to cope with the shallowness and meaninglessness of life like “happy” people could. I felt abandoned by the people I loved and yet still obligated to stay alive for them, to keep living in pain because it was cruelly unfair to hurt them the way my friend hurt me. Each lonely, empty day tested my self-control and eroded whatever hope I had that I would ever feel anything other than horribly depressed and utterly worthless. Eventually, willpower alone was not enough to guarantee safety while I grappled with my persistent suicidal thoughts. I realized how close I was to losing the battle one night and, lacking the courage to call someone I knew, called 911 to get help.

I couldn’t help but feel guilty during my five-day stay in the psychiatric ward. I had so many friends who needed help more than I did, yet there I was, getting treatment for something I believed I had brought upon myself. To my surprise and relief, the doctors treated me as they would any other sick patient, continually reminding me that depression was a medical illness and that this style of self-deprecating, invalidating thought was just a typical symptom. Their clinical approach helped me reconsider my sadness as stemming from circumstance and a chemical imbalance in my brain rather than my own inherent flaws and lack of optimism. Upon my discharge from the unit, the doctors recommended I do a partial-hospitalization program called La Selva, where I would attend therapy groups for five hours a day, five days a week, for eight weeks. I resisted; I did not want to fall behind in school and college apps. But my parents insisted that I needed longer-term care after I left the hospital. In order for things to get better, I had to put my health first and figure everything else out later.

On the first day of second semester, I went to group therapy at La Selva instead of school. La Selva didn’t magically cure me, but watching some of my peers’ moods slowly improve each week allowed me to see firsthand that recovery was possible. Because all of the patients were there for similar illnesses, I felt safe being my authentic self, whereas before I often felt the need to mask my sadness to avoid burdening others. Finally, I could relax and shift my attention fully onto my own issues instead of worrying about how my depression was affecting others. The patients were deeply empathetic, and whenever I spoke they made me feel seen, understood, and cared for, even though we hardly knew each other. Having the opportunity to talk through some of my painful experiences allowed me to begin to process them and heal from them. If at any point I didn’t feel comfortable to talk, I could listen, and hearing their stories gave me words to describe feelings I had experienced but had never been able to express.

In other therapy groups, we examined mental illness through a slightly more analytical lens. In these, I learned to be more deliberately conscious of my emotions, and to accept them as real and valid as a way to cope with them and regulate them. When I felt myself start to get sad, I practiced acknowledging my sadness’s growing presence and then allowing myself to really experience that sadness, without scolding myself for its arrival, getting frustrated or panicky, or trying to suppress it. Labeling the experience as “sad,” as though I were an objective onlooker making a simple observation, allowed me to detach myself from the emotion and wait patiently for the heavy feelings to pass. My emotion was not me: it was a foreign force that came and went in periodic waves, and because judging myself harshly for feeling depressed did nothing but make me feel more depressed, sometimes, I just had to endure it diligently. These groups also helped me become more aware of my thinking, and to question the legitimacy of my negative thoughts so that I could recognize how they were often distorted by my depression; when I recounted events, I often did so with a mental filter that magnified the negative aspects of those events and completely disregarded the positive ones. To change this deeply ingrained habit, I’d have to exert immense effort to be constantly aware of the way I was thinking and then challenge my distressed, irrational thoughts with neutral ones based in reality. It did help to realize that some of my most depressing thoughts were warped and illogical, but even though I consciously knew that, they were still there, and they still hurt. In hopes that my busy mind would calm and my mood would improve, my psychiatrist prescribed me a new medication to begin before I left the program and started school again.

Going back to school was discouraging. On my day of reentry, people seemed to look away from my suffering and pretend they didn’t see it. I felt invisible again. Just as before: I mattered only when I was laughing and happy. A few colorless weeks of school passed, and then I noticed a small but miraculous shift. Little had changed?—?school felt painful and lonely, and I ruminated frequently about the point of existence?—?but I was absentmindedly singing along to the radio again, something I hadn’t done in months. I could feel the new medication improving my mood and lessening my chronic fatigue. As I continued to take it daily, my thoughts, though still the same profoundly negative thoughts, became easier to recognize as irrational and did not carry quite so much emotion and despair. To be sure, antidepressants aren’t for everyone, and they don’t reduce the need for sleep and a support network; but for me, they played a pivotal role in giving me the motivation I needed to make changes in my life. The slight increase in energy allowed me to put effort into socializing again, spurring a chain of reconnection with old friends and even the pursuit of new friendships. The more time I spent with people, the more connected I felt and the more my depressive symptoms decreased. The happier I appeared, the more frequently people reached out to spend time with me. It was a cycle. My mood changed just slightly, and then, slowly, everything else followed.

Going back to school was discouraging. On my day of reentry, people seemed to look away from my suffering and pretend they didn’t see it. I felt invisible again. Just as before: I mattered only when I was laughing and happy. A few colorless weeks of school passed, and then I noticed a small but miraculous shift. Little had changed?—?school felt painful and lonely, and I ruminated frequently about the point of existence?—?but I was absentmindedly singing along to the radio again, something I hadn’t done in months. I could feel the new medication improving my mood and lessening my chronic fatigue. As I continued to take it daily, my thoughts, though still the same profoundly negative thoughts, became easier to recognize as irrational and did not carry quite so much emotion and despair. To be sure, antidepressants aren’t for everyone, and they don’t reduce the need for sleep and a support network; but for me, they played a pivotal role in giving me the motivation I needed to make changes in my life. The slight increase in energy allowed me to put effort into socializing again, spurring a chain of reconnection with old friends and even the pursuit of new friendships. The more time I spent with people, the more connected I felt and the more my depressive symptoms decreased. The happier I appeared, the more frequently people reached out to spend time with me. It was a cycle. My mood changed just slightly, and then, slowly, everything else followed.

Now, I feel much better than I felt pre-hospitalization, or even just a few months ago. Recovery is a long and difficult process; inevitably, I sometimes still wake up feeling hopeless and empty for some reason, and on these days I try to be extra kind to myself. But most days, I feel okay, and the number of days I feel good is increasing. I finally stopped putting my well-being on hold, and I’ve been more compassionate and patient with myself ever since I started to think of depression as a sickness instead of a fabrication. Rather than blame myself for the thoughts and feelings I cannot control, I blame depression for shaping them into what they are. I remember that emotions are temporary, and I practice letting the bad ones go and appreciating the good ones that come.

Though the past year has taught me that I must take care of myself before attempting to care for others, I don’t regret all the time and effort I put into being there for my friends. Their willingness to confide in me and ask for support is not what exacerbated my depression; on the contrary, it allowed me to form the deeper, more meaningful connections I had craved for years. But now I see that trying to hold their lives in my hands and take responsibility for their safety was unhealthy; it exhausted me, and it prevented them from seeking the professional help they truly needed. From now on, I will support my friends differently, reminding myself that the best I can do for them is provide them with love, compassion, and encouragement to seek out the people who have the proper education and training to help them get well again. And unlike before, when I ignored my own experience and denied myself the same validation I gave to my friends, I will remember to be aware and trusting of my own feelings, too, as well as vulnerable and honest about when I need more care.

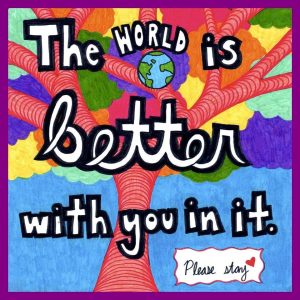

This is me being vulnerable, because I didn’t know how to be vulnerable when I was at my worst. As with any process, there will undoubtedly be more roadblocks on my path to getting well; when I meet them, I must remember that despite how hopeless I may feel and how persuasively my mind may trick me into wanting escape more than seeking help, I need to trust in professionals to find the best care for me and my family and friends to love me even when I feel and trick myself into believing no one does. I hope publishing this piece will inspire others to be vulnerable, too, and reach out to someone, whether to offer help or request it.

If you are worried about yourself OR a friend, to be directed to professional help, contact

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1–800–273–8255, 24/7 access to trained counselors

School counselor/psychologist

Your doctor

suicidepreventionlifeline.org and click “Get Help” for yourself or for a friend

If the threat is immediate, call 911

mom2tnt • Nov 28, 2016 at 5:30 pm

Our family owned a dessert shop in Mountain View frequented by students from Gunn/Palo Alto High and right in front of one of the CalTrain station. It was there that I learned about the cluster of suicides that occurred in the area. I came to recognize many of the young faces that came through our doors, including the effervescent Lindsay, and her group of friends. We loved having a place for the kids to hang out. After we closed the store, I heard that one of the students I knew ended his life. My heart broke then and continues to break everytime I read about the silent pain and suffering endured by these young folks because of stress or mental illness. I’m happy to hear that many have reached out for the help they need. I’ll always remember and be grateful for the light they were for me during the time they were in our lives. Thanks for sharing, Lindsay, and best wishes to you in the future.