Written By: Akansha Gupta and Stephy Jackson

Over the past few decades, anti-racism activism has taken great strides. It’s gotten to the point where it’s hard to believe that fewer than 65 years ago, segregation was legal in the United States. Most people today believe that racism is valiantly being fought against, if they don’t already consider it a non-issue. This sentiment is evident in statements which point proudly toward our last president, an extremely qualified black man. However, even the most optimistic have to admit that systematic racism has left behind a legacy of implicit racism.

Systematic racism and implicit racism are often confused because they are so intertwined with each other. Systematic racism oppresses minority races by means of legislation and policy, while implicit racism is usually subtler and often unintentional. Pop culture, news outlets and individuals all play a role in reinforcing it.

This implicit racism perpetuates systematic racism and creates

a vicious cycle of minority races being told they are not good enough. One place this is

illustrated is in the job market. According to a field study by the National Bureau Economic Research (NBER), given that two candidates for a job have the same resume, the candidate with the “white name” is more likely to get the job than an identical candidate with a “black name.” In fact, job applicants with African-American names needed to send about one-and-a-half more resumes to get the same callbacks as those with white names. Although the employers probably did not intend to act upon subconscious biases, implicit racism caused them to discriminate against candidates with “black names.”

Implicit racism is not just a hurdle for black Americans to overcome when it comes to employment; it exists in pop culture as well. Furthermore, black Americans are not the only minority hurt by implicit racism. Stereotypes cementing Asians as quiet and nerdy and Latinos as gang- members are reinforced over and over by music, books, TV shows and movies where non-Caucasian characters are cast in supporting roles. Asian and Hispanic characters especially are used as unimportant sidekicks or villains that need to be defeated.

When magazines like “Seventeen” and “Covergirl,” which help shape beauty standards for women and teenage girls, feature famous women of color like Beyonce or Jennifer Lopez on magazine covers, they are whitewashed and often appear with fairer skin and colored contacts.

When editors, directors and scriptwriters try yo amuse their audience by falling back on old stereotypes, it can be debilitating to children and teenagers from minority groups. For

example, when magazines like “Seventeen” and “Covergirl,” which help shape beauty standards for women and teenage girls, feature famous women of color like Beyonce or Jennifer Lopez on magazine covers, they are whitewashed and often appear with fairer skin and colored contacts. This is bad for the self- image of women of color because pop culture bombards them with the idea that they need to look white to be beautiful.

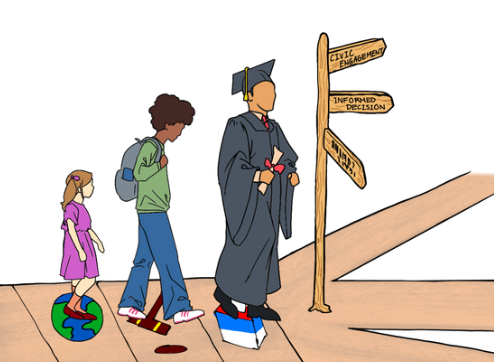

Compared to their white counterparts, young adults from Asian, black, Hispanic and Native American backgrounds have to put in more effort to find funny, intelligent, beautiful and inspiring characters who look and sound like them in pop culture. Though it is not the only thing which discourages minorities from higher education and certain fields of education, lack of viable role-models in pop culture might contribute to the lower percentage of minorities who go to college and seek jobs that can put them in the highest income brackets. To change this, artists, script-writers, authors and directors have an obligation to create realistic characters who can inspire people from minority groups.

Incidents where stereotypes and implicit racism insulted and hurt people from minority races appear regularly in the news. Stores like Versace, CVS, Apple and Best Buy have appeared in the news for treating minority customers with suspicion and even unfounded accusations of shoplifting instead of the helpfulness one might expect as a customer. Although the accusations may come from well- intentioned employees trying to curb crime, their overreaction is a result of implicit racism, which has conditioned people to believe that black customers are more suspicious. Additionally, these accusations also contribute to how society negatively views black people.

Some people who do not consider these incidents important are quick to proclaim themselves “color-blind” when it comes to race. An article by “Psychology Today” describes color-blindness as a racial ideology which suggests the best way to end discrimination is by treating individuals equally irrespective of race, culture or ethnicity. It goes on to say that most of the people who espouse this theory are part of a cultural, religious and racial majority; they don’t notice that the negatives outweigh the positives for minority groups. Color blindness creates a society that not only denies minorities’ negative racial experiences, but also rejects their cultural heritage. America is diverse because its citizens are not just of different races, but of different religions and cultures as well. Ignoring race— an important part of most people’s identity—is not a viable solution. Doing so will lead to diversity being ignored which will once again feed into the cycle of racism.

To fix the problems that are caused by implicit racism and implicit racism itself, Americans need to focus on the one thing that the country has always prided itself on—inclusivity.

To fix the problems that are caused by implicit racism and implicit racism itself, Americans need to focus on the one thing that the country has always prided itself on—inclusivity. Members of the community should make an effort to learn and interact more with those who come from different backgrounds.

It will take a concentrated effort from private individuals and popular culture to change the way people think about racial minorities, but if it can end the cycle of implicit racism, it will be worth it.

—Gupta, a senior, is a Tech Editor and Jackson, a sophomore, is a reporter.