Written by Sohini Ashoke and Joanna Huang

It’s a daunting task to start a new life in a foreign country, let alone learn a new language and adapt to a new culture. But for many students in Palo Alto, their parents have done just that. Whether they came for education or in search of better jobs, these parents have affected how their children see the world. As second-generation citizens, or the children of immigrants, these students have grown up in a multicultural environment, a different American experience.

Work Ethic

For junior Andrew Dong, whose parents immigrated from China, remembering the stories of his parents whenever he feels unmotivated helps him have a greater work ethic. “I feel it’s an injustice or unfairness to my parents if they worked incredibly hard to let me have a good life or better opportunities than they have and if I just turn around and squander that; that’s definitely not fair to them,” Dong said. “I would feel betrayed if I were them.”

Growing up, junior Avital Rutenburg remembers witnessing the large workload her mother, who immigrated from Russia, completed on a daily basis. “My mom would drop all three of us [siblings] off [at school], go to law school, go to a bunch of jobs after and come home after and read to us and make sure we felt loved. She was young while [doing] all of that, only 25,” Rutenburg said.

Rutenburg learned of the importance of ambition and hard work through her mother’s example. “My mom still has that hard work sentiment and she always tells us that no matter where we start, we have to work hard and compensate with whatever we have. And we cannot let our situation stop us and rather use our situation to help us out,” Rutenburg said. “Even though she started out with absolutely nothing when she came here, not knowing English, she didn’t settle and didn’t let it stop her from achieving the American dream.”

Expanding Perspectives

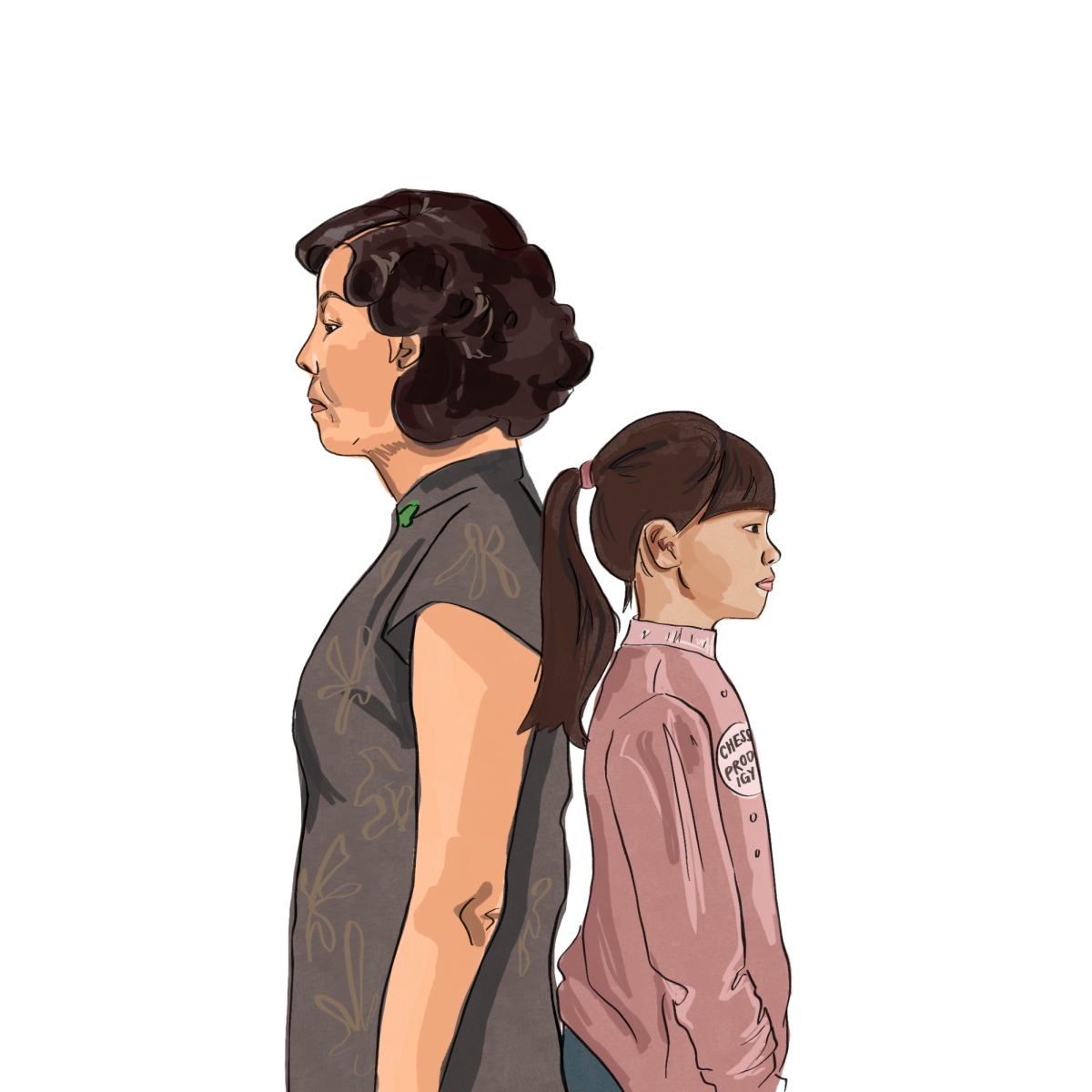

According to junior Minna Mughal, immigrant parents not only bring a great work ethic to America, but also an international perspective. Mughal, whose parents immigrated from Pakistan, recalls an upbringing different from that of her friends. “Growing up, I always just thought [how my family raised me] was the norm. I didn’t think my family operated differently, but now I realize that it’s honestly not how it is,” Mughal said. “I feel like sometimes I put expectations that [my parents] can’t meet because they parent a certain way but I’m trying to be parented like my friends are, which my parents don’t always agree with. It’s a bit of a struggle sometimes when I’m just trying to be like a regular American teenager when my parents are like Pakistani people.”

Rutenburg also recalls a childhood immersed in a different culture. “Growing up with my immigrant parents was very different from American families because growing up, I was basically in Russia,” Rutenburg said. “I would listen to Russian music, watch Russian movies, eat Russian food, speak Russian and I went to Russian schools.”

According to Dong, besides differences in parenting styles, having immigrant parents offers a new perspective on politics and world issues. “I’ve seen a lot more political views firsthand from China and the U.S., which are seen as political opposites,” Dong said. “Even though a lot of people might say it’s like a communist country or things are really bad there, there is a special place in my heart for it.”

For senior Keshav Nand, whose parents are from India, having immigrant parents helps him be more respectful of other cultures in general. “One thing might seem completely meaningless to someone, but to another person it could be so important,” he said. “[Learning about different cultural values] kind of helps me understand that people have their reasons for doing things, so I learned to respect them for it.”

Stigma

With the unique cultures of immigrant parents can come stigmatization. Pop culture often portrays Asian parents to be unemotional or strict, but Dong finds his parents are actually very supportive and friendly. “They’re really active in reminding me to do things I want to do, to pursue those interests,” Dong said. “I think that’s a really good thing to have.” Dong’s parents had to suppress their passions for sociology and art in order become engineers and make money in America. “They put a ton of effort into their whole lives just so that I could be born in a good place and have a good spot to start my life, so that definitely motivates me to work on my passions,” he said.

When he does not agree with his parents on political or moral issues, Dong resolves disagreements with his parents by recognizing the generation gap and cultural differences. He acknowledges their efforts to avoid the mindset encouraged by the rigorous and competitive academic atmosphere of China in order to adapt to America’s free-form atmosphere. “They’re kind of liberal for Chinese parents anyway; normally a lot of parents are heavily focused on STEM [science, technology, engineering and math] and want you to go to an engineering career, but my parents are pretty lax with the specific direction that I’m going in,” Dong said.

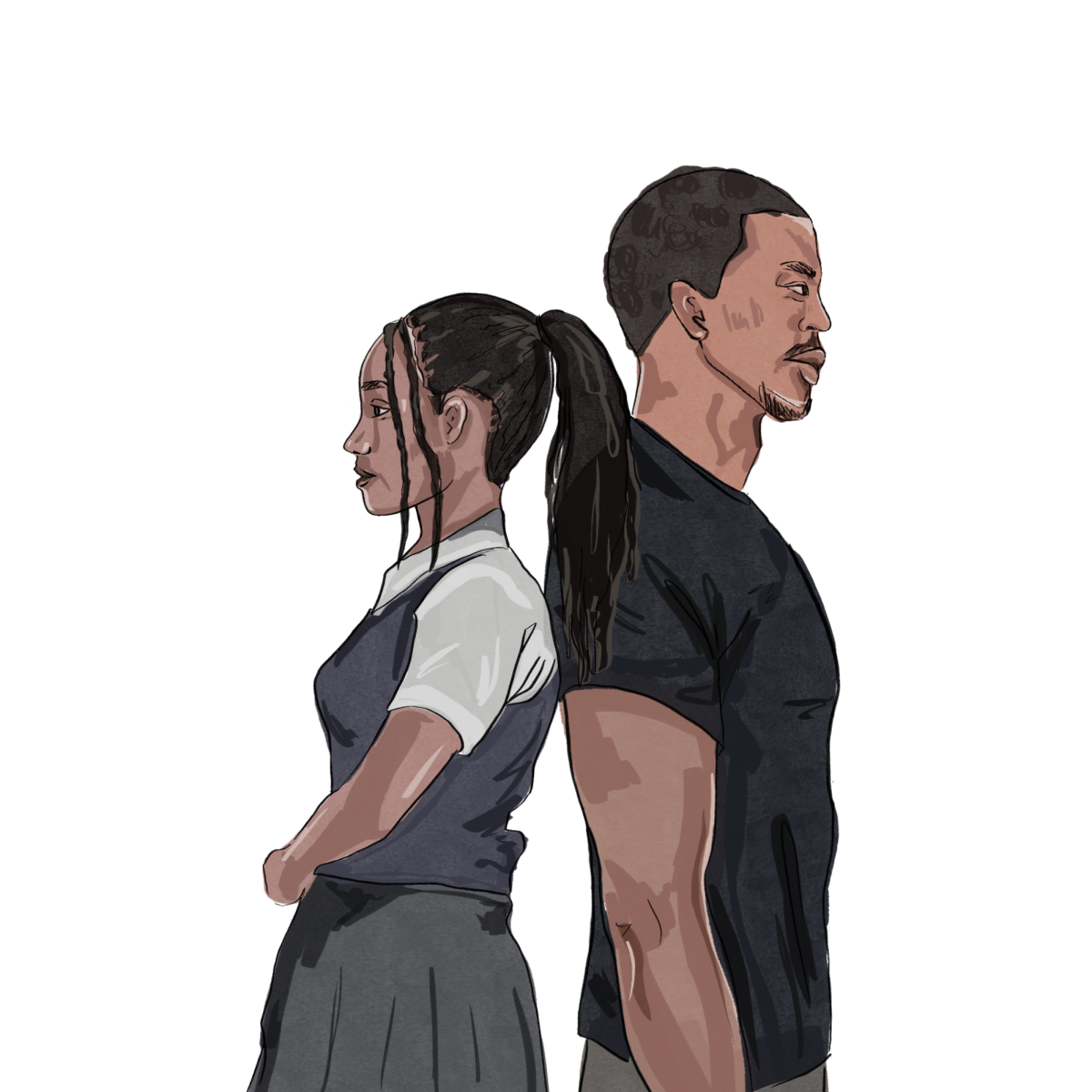

Sophomore Libbey Castleman’s mother is from Eritrea, and moved to the United States because of the opportunity to achieve her dreams. “The idea of the American dream and being able to do anything in the United States was really inspiring to her, and there was a lot she wanted to see in this country,” Castleman said. Having one immigrant parent and one non-immigrant parent caused challenges in her childhood, especially in how she identified herself. “My mom is from Africa and my dad is from here, and they are complete polar opposites,” Castleman said. “I never looked like them so I thought it was really weird. I was set apart from other kids, and I got asked if I was adopted a lot.”

Castleman has also faced discrimination from others because of her identity. “I’ve had people say names to my face, say names behind my back, racial slurs to me or my mother or to anyone who is dark colored in my family,” Castleman said. “Even though I am not as dark as my mother, I know I will never be a white person, but it’s not something I want to be, because I am happy with who I am and the race I am.”

Positivity

Despite the host of disadvantageous and possible prejudices that come with being a child of immigrants, Castleman still views her identity in a positive light. “[Having immigrant parents] definitely sets you apart, but it’s something that you should embrace and take advantage of and feel grateful for,” Castleman said. “I think it really helps shape you as a person and it’s something that is so great to be a part of.”

However, according to Dong, cultural exploration is not limited to second-generation immigrants; even children of non-immigrant parents can benefit from analyzing their background and identity. “I think spending the time to recognize your own history and who you are as a person is really beneficial to helping your own development,” he said.