Written by: Akansha Gupta

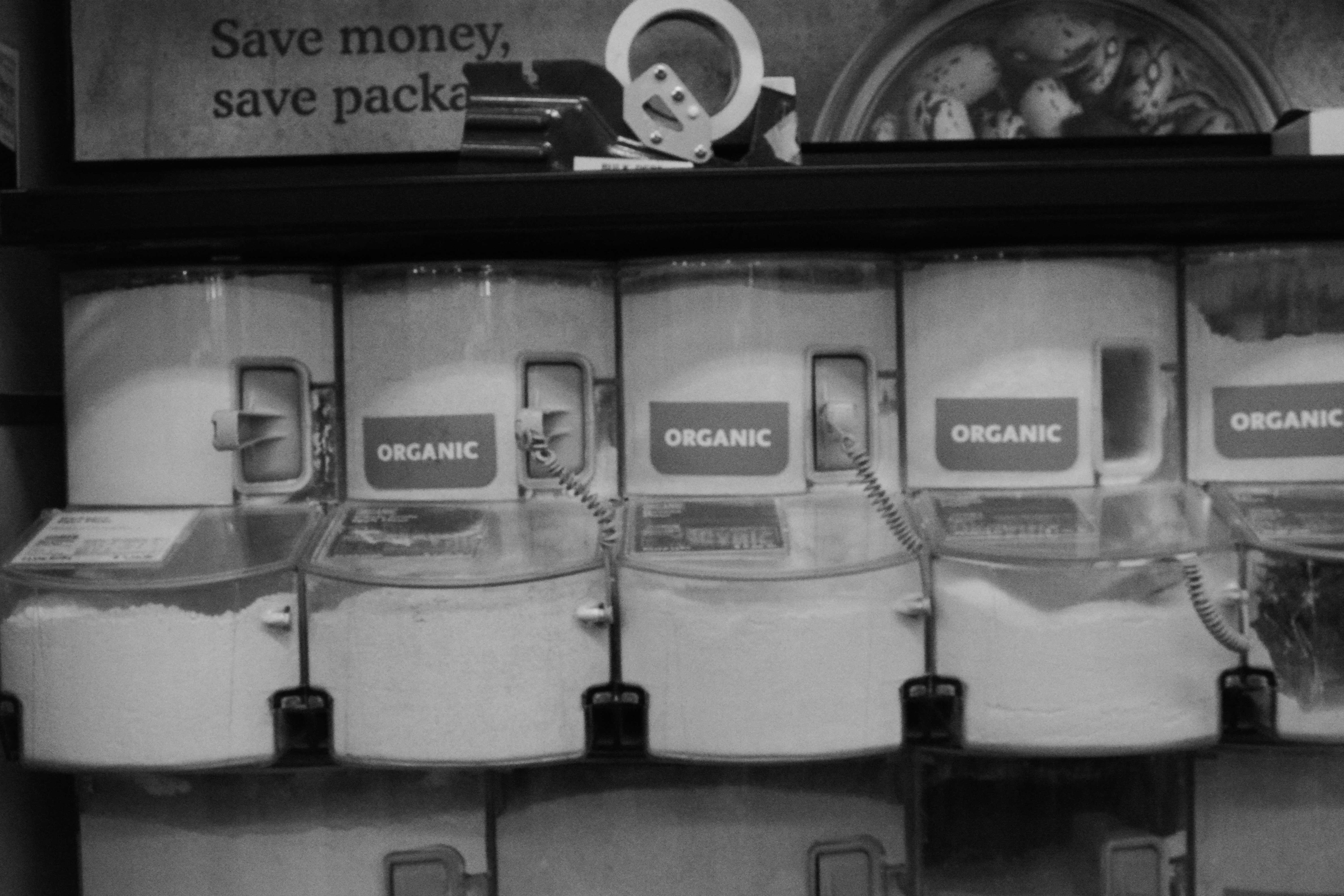

Ostensibly, conscious consumerism encourages people to only purchase items that are produced ethically and in a sustainable manner. Catchy phrases like “vote with your dollar” and “put your money where your heart is” are thrown around, and they make it sound like reducing child labor or ensuring the air remains breathable for another decade or so is as easy as opening up your wallet. However, the reality is that buying products that are truly produced ethically and sustainably is much more difficult than choosing between a couple of labels. Conscious consumerism does not have a significant impact on one’s carbon footprint. These two factors combine to make mindful consumerism ineffective.

Conscious consumerism has been heavily criticized for being elitist. After all, it takes a good amount of disposable income to buy products that have been sustainably and ethically produced. The companies tend to be smaller and lack the advantages that economies of scale provide; these companies have to charge more to earn a profit. Additionally, a lot of their products are, quite frankly, not as good. Ecosia, a search engine which promises to donate a portion of its proceeds to plant trees, has fewer search results than established companies like Google. In an interview in 2014, a founding member of Ecosia said that the company had no plans of creating an algorithm to become an independent search engine because they did not have the resources to do so (they’re donating 80 percent of their profits).

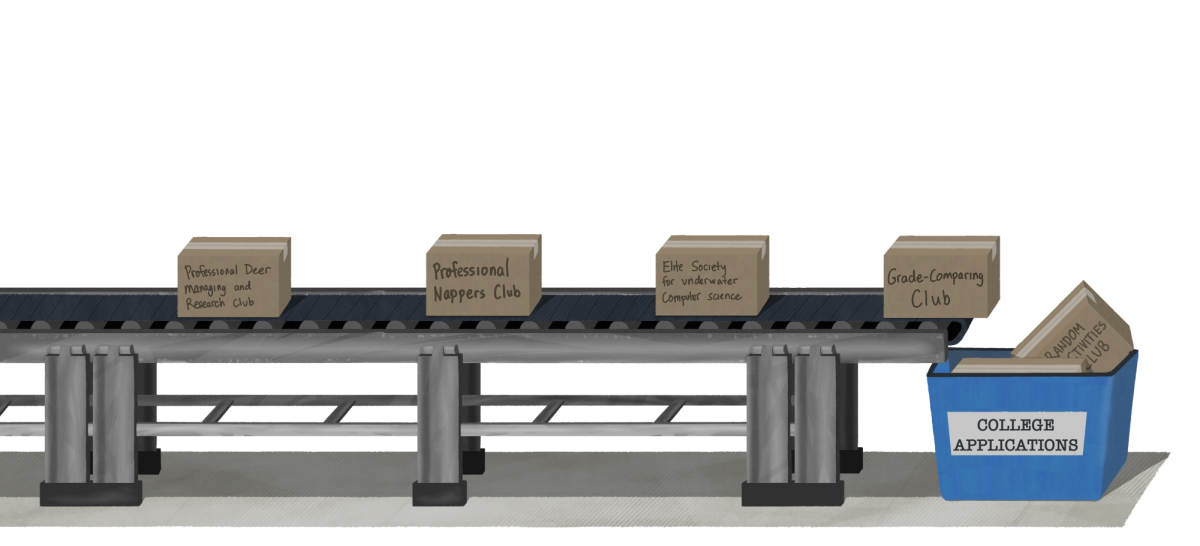

A truly conscious consumerist lifestyle is not just limited by one’s disposable income, but also by one’s time and ability to research different products thoroughly. After all, several people have shown that they are willing to pay more for ethically and sustainably produced products and some unscrupulous sellers have decided to take advantage of consumers’ willingness to do so by advertising their products as greener than they actually are. For example, Clairol’s Herbal Essences, which claims to be a “truly organic experience” contains lauryl sulfate, propylene glycol and D&C red no. 33, which are distinctly synthetic. This phenomenon is not strictly related to beauty products and cleaning agents; it has become so common that the term “greenwashing” has been coined and used to describe products which run the gamut from airplanes to software.

Aside from marketers who intentionally mislead consumers, truly conscious consumers need to do an almost impossible amount of research into the intermediate goods required to make an end-product. For example, those who are insistent on buying locally produced T-shirts may have done their research and ensured that the company that produced their T-shirt was an American one which obeyed labor laws. However, if they want to be truly conscientious, they must consider that the actual cloth for the T-shirt may have been produced in a sweatshop halfway across the world and that the cotton used to make the cloth may have been harvested by children. In this fashion, it is almost impossible to say what you’re voting for with your dollar. The idea of putting your wallet where your heart initially sounds charming, but it’s overly simplistic and naive. Even as you vote to increase American manufacturing, your dollar might effectively contribute to maintaining the status quo which takes advantage of child labour.

Aside from marketers who intentionally mislead consumers, truly conscious consumers need to do an almost impossible amount of research into the intermediate goods required to make an end-product. For example, those who are insistent on buying locally produced T-shirts may have done their research and ensured that the company that produced their T-shirt was an American one which obeyed labor laws. However, if they want to be truly conscientious, they must consider that the actual cloth for the T-shirt may have been produced in a sweatshop halfway across the world and that the cotton used to make the cloth may have been harvested by children. In this fashion, it is almost impossible to say what you’re voting for with your dollar. The idea of putting your wallet where your heart initially sounds charming, but it’s overly simplistic and naive. Even as you vote to increase American manufacturing, your dollar might effectively contribute to maintaining the status quo which takes advantage of child labour.

Studies have found that in first-world countries like America, conscious consumerism doesn’t significantly reduce the carbon footprint. The American lifestyle is inherently wasteful because fashions are replaced almost every season and other goods are replaced instead of repaired when they are broken.

Conscious consumerism is a manifestation of first-world guilt because it allows consumers to feel good about themselves without making a real difference. Conscious consumerism is an indulgence, and it should be treated as such. This year, global consumers are expected to spend $3.22 billion extra in green cleaning products by themselves. This money would be much better utilized in lobbying governments to ban the most harmful chemicals so that they don’t end up in water runoffs. As for companies like Patagonia which promise to give a small portion (1 percent) of their proceeds to charity, it makes sense to donate directly to charity instead of relying on an intermediary to do good on your behalf. If people want to make a real difference in the environment, they would be better served by volunteering their time to NGO’s which are actually making a difference in the world. Additionally, they can donate the extra money they would have spent on products which are supposedly ethically and morally superior to organizations which have a proven track-record and a history of utilizing their money well.

In privileged communities, conscious consumerism may be the trendy and easy way to steer the world. After all, all you need to do is buy products that are touted to be green and clean. However, easy doesn’t necessarily mean effective.