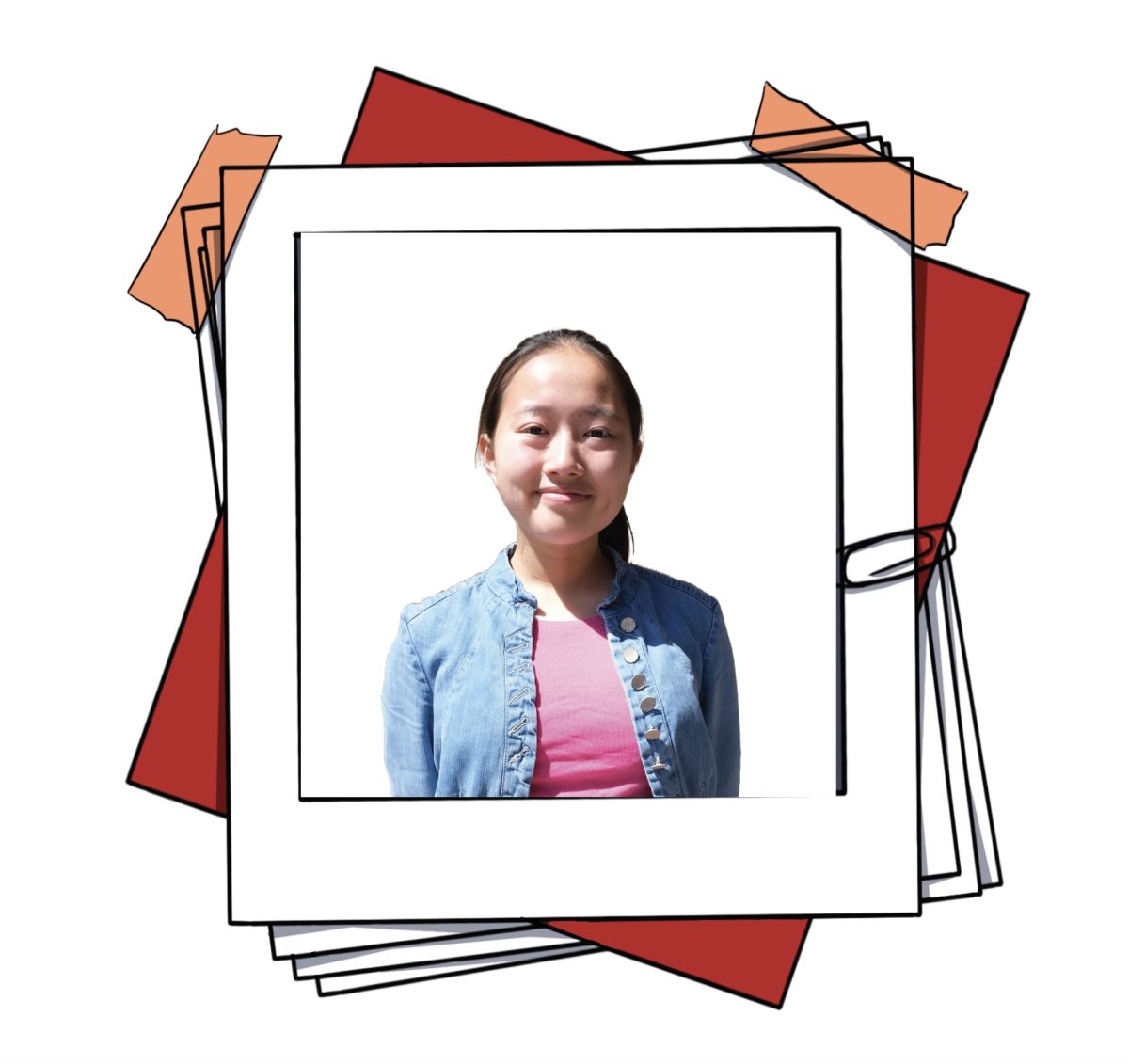

Written by Kaya van der Horst

To freshman Matias Zirulnik, at first glance, Gunn’s campus seemed more like a scene out of Baywatch than it did a school: life guards patrolled the quad while a mermaid was spotted walking down the steps of the N-Building. On their first day of high school, 478 wide-eyed freshmen were welcomed by the senior class decked out in their pool-party themed costumes. While being new to a school can always be stressful in itself, Zirulnik had to navigate through an additional novelty: adjusting to life in a new country.

On Aug. 7, Zirulnik moved to the United States from his lifelong home in Santiago, Chile with his older brother Lucas and his mom. “My mother wanted to study at Stanford [University] and she wanted me and my brother to be with her so we came too,” he said. “We’re only staying here for eight months until my mom finishes her education.” Afterwards, the Zirulniks will return to Santiago in March.

In Chile, the academic school year runs from March to December with two weeks of winter holiday in July and summer holidays from mid-December to March. Because of this calendar, Zirulnik technically never finished eighth grade as he left in the middle of the school year in August. “Initially, I was scared of leaving all my friends, but then I thought it’s going to be a very good experience for me,” he said. “Besides, I’m going to improve in English a lot.”

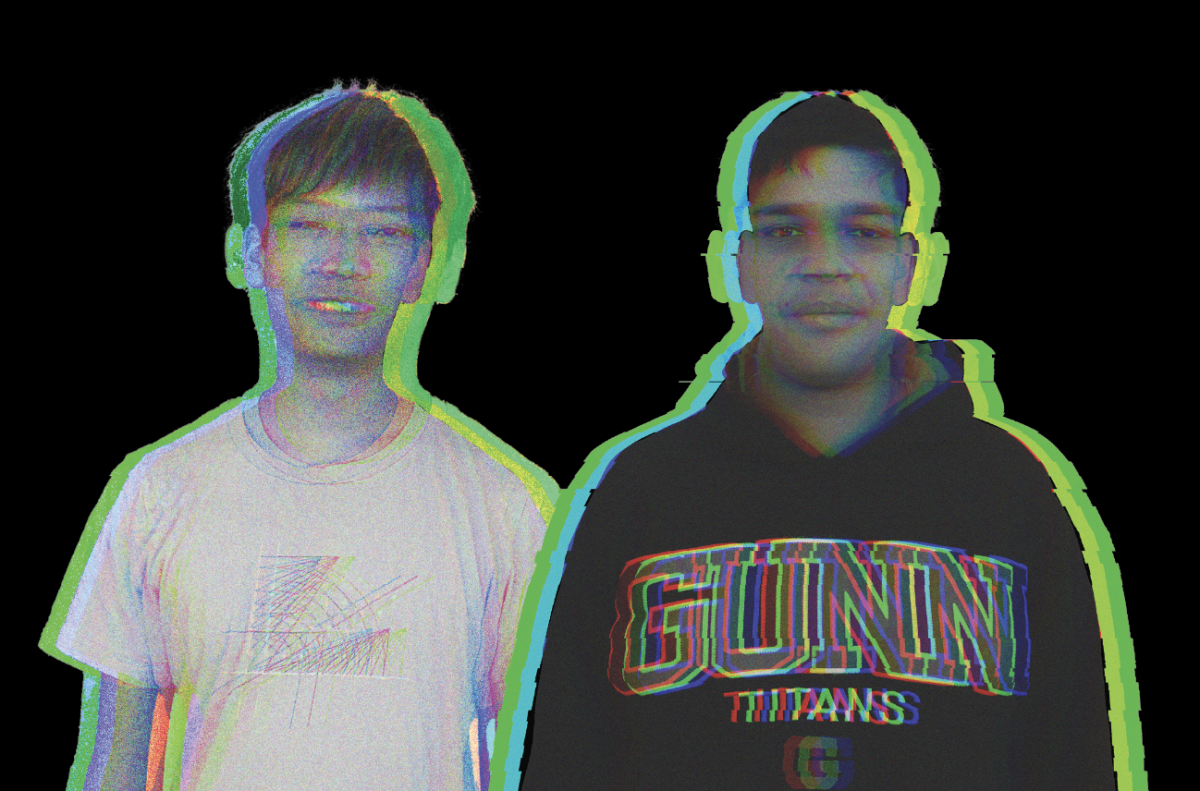

Fortunately, language has not been a huge barrier for Zirulnik as he attended Andrée-English School, a bilingual private school in Santiago. “I realized that when I say I’m from a private school, people look at me like I’m weird because [private schools here are] much more expensive than the private schools in Chile,” he said.

One of the immediate differences Zirulnik noticed between Gunn and his old school was the size—Andrée-English school had the size of Gunn’s population split up into 12 grades, meaning the grades were much smaller. Additionally, students remained in one homeroom during the entirety of the day. “In Chile we don’t change rooms from class to class,” he said. “The teachers change depending on what class they have.”

While it can be overwhelming to make friends in a grade of nearly 500 students, the small size of his old school allowed for a tight-knit community and fostered more meaningful relationships. “We stay together as classmates for the entire 12 years of school in Chile, so we get to know each other more than here,” Zirulnik said.

In terms of education, Zirulnik has noticed Chile places a stronger emphasis on memorization—a stark contrast to Palo Alto’s educational approach of problem-based learning and applicable knowledge. “Here you have to think more about the problems and in Chile you just look at the problems and have to memorize how to do it—if you don’t, you’re not going to do well in school,” he said.

Since his move from Santiago, biking has played a large role in Zirulnik’s newfound independence. “In Chile I was dependent on my mother for rides or had to use the bus,” he said. “It’s kind of like more freedom here because I can go wherever I want.”

Along with his new mode of transportation, Zirulnik has embraced other opportunities through his involvement in Quantum Physics Club, choir and tennis. “Choir is fun but I don’t think I will continue it when I come back home because in Chile it’s only really girls in the choir,” he said. “I want to continue tennis in Chile though.”