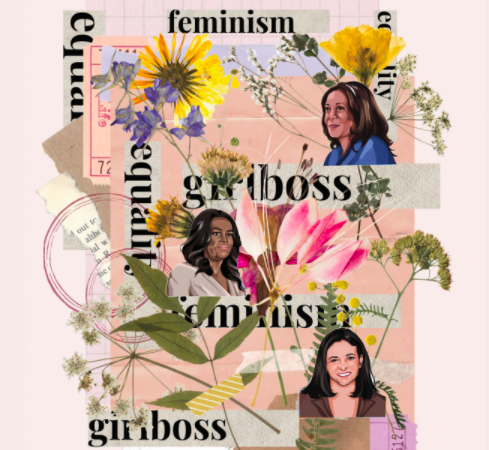

Girlboss: the good, the bad, and the ugly

How toxic feminism has impacted the Women’s Rights Movement

In 2013, late night host Eric Andre invited singer Melanie Brown onto his talk show to ask a simple question: “Do you think [former British Prime Minister] Margaret Thatcher had girl power?”

“Yes, of course,” she responded.

He followed up: “Do you think she effectively utilized girl power by funneling money into illegal paramilitary death squads in Northern Ireland?”

Brown was clearly caught off guard and simply responded with, “I don’t know about that.”

Margaret Thatcher was the first female prime minister of Britain—yet left a complex legacy. Although she broke a myriad of gender barriers, she simultaneously garnered an unfavorable reputation as she disregarded women’s rights, sparked the rise of British nationalism and shunned labor groups. Thatcher, however, is hailed as a feminist icon despite having arguably done nothing to deserve that title.

Thatcher is a case in point of a larger issue: With the lack of representation in a male-dominated society, we often overlook politics and personal views simply for the sake of putting strong women in power; women who have downright horrible or even anti-woman policies are excused just because they’ve broken new ground or shattered glass ceilings.

This phenomenon holds many names—it can be called corporate feminism, neoliberal feminism or girlboss feminism. Yet the common denominator is that all these terms stress the influence of a woman with no actual regard to what that woman has done.

Certainly, at a point when gender equality was still a burgeoning issue, those who fought for the cause stood out among the rest. That’s why we often remember women’s rights champions such as Susan B. Anthony in glowing terms, despite their—in Anthony’s case—racist or otherwise unscrupulous views.

There is no shortage, however, of strong, intelligent and powerful women who are outstanding individuals. To truly be a feminist icon or a girlboss, one should not just be a woman in power, but also one who works to uplift other women and utilizes that power to enact structural change.

An Empty Gesture

What exactly is a girlboss? The term originated from the founder of clothing retailer NastyGal, Sophia Amoruso, in her memoir, “Girlboss.” The term was originally used as a way to describe a strong, empowered woman.

It’s a definition that has endured, at least for some. “[When I hear the word girlboss,] I think of girls being themselves, powerfully, unequivocally,” answered a student on a survey sent out by The Oracle. “I see them taking on roles traditionally assigned to men, and making them theirs.” Many survey respondents also saw “girlboss” as an empowering term for women, one that signified their strength.

The term was also often associated with the business world and corporate entities. “A girlboss is a girl or woman who is in a senior position at a company or organization,” noted one student. “Female CEO or successful businesswoman,” wrote another.

Indeed, it’s in this context that the term girlboss begins to stray from its originally positive intentions and lean more towards defining worth through financial success.

The financial focus of the term’s connotation has been criticized. “The term puts a price on feminism,” a student wrote on the survey. “Implying a girl should just rise up the ranks of a corporation to earn respect devalues their identity as a woman and puts value on their identity as a superior. A woman shouldn’t have to be at the top of a corporate ladder to be respected.”

The term “girlboss” itself draws similarities to a statue of a young girl facing down the Wall Street Bull in New York City, titled the “Fearless Girl.” The original intent of the statue was to encourage workplace gender diversity and promote female empowerment.

Ironically enough, the firm that paid for the statue was subject to a 2017 lawsuit alleging that they didn’t pay their female staff members equally. And that’s exactly emblematic of the issue with girlboss feminism: It can often be nothing more than an empty gesture—a symbolic action with no actual change.

“I think that on the one hand, the whole term of a ‘girlboss’ in particular is infantilizing,” English teacher Kate Zavack said. “It’s also reinforcing capitalistic structures at the same time.”

The elements of corporate feminism are also often found in advertising targeted to women and stressing the importance of so-called “Girl Power.” In 2019, McDonald’s flipped their iconic double-arch M into a W to signify International Women’s Day, a move that was widely hailed as insincere and performative. “I don’t think [corporations] should market diversity for the sake of getting money,” freshman Antonia Minion said. “It should be for the sake of actually, you know, striving for a change.”

Zavack agreed with the sentiment, especially when it comes to the commodification of feminism. “We see a similar ethos in a lot of advertising now—marketing razors or soap as a feminist product—when really all that’s doing is making money,” Zavack said. “They’re using feminism to make money.”

Even details as small as the actual word “girlboss” can be carefully placed corporate marketing. “I think that it’s essentially marketing—it’s a phrase that’s designed to get the individual to feel like they are empowered,” Zavack said. “But it doesn’t actually give them real power, and it doesn’t change how power is distributed beyond the individual.”

The Politics of Representation

Women in positions of power, such as in politics, are often seen as a progressive ideal, which can undermine them when women begin to be defined by their womanhood and not by their policies and views: Criticize Vice President Kamala Harris’ past actions as a prosecutor, for example, and suddenly you’re sexist, or level a critique on House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s reauthorization of the Patriot Act, and you’re using a double standard on a powerful woman.

“With [Vice Presidential Candidate] Sarah Palin, or [Supreme Court Justice] Amy Coney Barrett, or any of these women, their identity as a woman is used to either excuse their actions or to rhetorically attack the other side [by] saying, ‘Oh you don’t support women in power,’ when really, it’s just excusing their beliefs that do not make women’s lives better,” Zavack said.

The line between sincere representation and performance can easily blur, however. “I know some companies who put one woman

on their board of leaders and are like, ‘girlboss, we’re so progressive,’” Minion said. “No, you’re really not. But I think it can also be incredibly powerful and good if a company is actually striving towards not only symbolically having women leaders but actually making change.”

Still, there are ongoing efforts to increase positive representation for women, especially on a community level. “STEM is a male-dominated field, and it always has been,” Women in STEM Club Co-President junior Sarah Bao said. “Our goal is to create a space where women at our school who are interested in STEM can come together and talk about interests, and we can just support each other and make each other comfortable in our journeys in STEM.”

This camaraderie can serve as valuable encouragement, as it turns achieving gender equity into a group effort rather than placing all the responsibility of breaking these barriers on a single person. “Seeing female role models in STEM can push women to pursue STEM,” Bao said. “It becomes the new normal, so it’s not crazy anymore.”

Working together as a group of women can help dispel a needlessly competitive atmosphere. “Traditionally, women have had this

thought of, ‘Well, they’re only going to let one woman on the board and I’ve got to be better than the next woman in order to get there,’” CEO and co-founder of Snowball Print Marketing Katrina Shaw said. “I think real confidence, real feminism, is not, ‘I’m great and she’s not,’ it’s ‘I’m great, so is she.’ That’s real confidence, that’s real feminism—there’s room at the table.”

Similarly, a diversity in educational material can be empowering. According to Zavack, more or less diversity in readings can often send subliminal messages to students. “Having voices represented is one step,” Zavack said. “It sends an implicit message about whose experiences, whose intellect, are worth celebrating and honoring and studying.”

Uplifting Women Everywhere

The image of a girlboss is often one associated with financial success or corporate leadership. Women with more “traditionally” feminine jobs, such as stay-at-home moms, are often looked down upon for conforming to gender roles. Yet true feminism should work to uplift women, wherever they are.

To truly break free from that narrative, according to Shaw, it’s essential to unlearn the image of the lone woman in the boardroom, and collectively realize that strong women exist in all facets of the world. “Women tend to tie up our self-worth in our productivity,” she said. “‘I’ve done all these things so therefore I must be a person of value.’ I think women should be free to choose if they want to be someone who earns a great deal of money in their life or [if] they’ve decided to be a homemaker.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Henry M. Gunn High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.