Students should consider criteria other than selectivity, prestige to measure education value of college experience

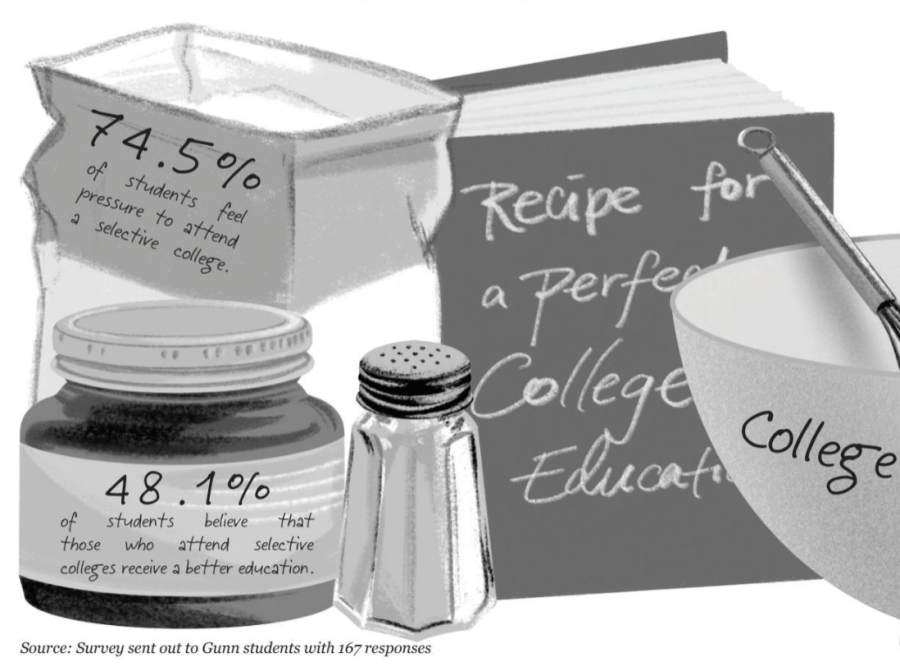

Obsession with college selectivity and prestige is a ubiquitous phenomenon. A quick surf on YouTube reveals a whole host of “college decisions reactions,” including tantalizing thumbnails with phrases like “How I Got Into MIT and Yale” or “I Made it Into the Most Selective College in the Nation.” Look on a seemingly innocuous website about the college application process, and there’ll be an article by a Harvard alumnus on how you can get into the Ivy League too. This isn’t to mention what students hear within school; even informal comments like “You’re so smart! You’ll probably go to Stanford!” reveal this single-minded focus on “elite” selective schools. Many in the pressure-cooker Silicon Valley environment feel that selectivity and prestige are synonymous with education value when it comes to the college search, and this fallacy is a dangerous one to fall prey to. Instead of perpetuating this mindset, students should expand their definition of education value, giving heavier weight to factors that can more accurately capture what they want to gain from the college experience.

According to Jeffrey Selingo’s book “Who Gets In and Why: A Year Inside College Admissions,” the use of the word “elite” to describe colleges wasn’t even commonplace until after the 1940s, when it surged in popularity. “An elite college now is almost exclusively defined by how hard it is to get into,” he writes.

Part of this new definition has been the evolution of the U.S. News college rankings system, which rates colleges across the nation. Currently, there are nine major criteria considered, each with a different weight in the overall ranking. These factors are graduation and retention rates (22%), social mobility (5%), graduation rate performance (8%), undergraduate academic reputation based on peer assessments by other colleges (20%), faculty resources (20%), student selectivity (7%), financial resources per student (10%), alumni giving rate (3%) and graduate indebtedness (5%). Based off of this alone, it’s evident that the rankings favor selective, wealthy colleges—they give low weights to categories that most profoundly influence life after college (such as indebtedness and social mobility), while prioritizing criteria which don’t represent what students actually learn within a college and can be easily manipulated (such as peer assessments). Historically, this manipulation has occurred: colleges lower in the rankings have attempted to “game” the system, increasing selectivity and extricating favorable peer assessments from other colleges in order to improve their standings. In this way, schools can make surface-level changes without improving the quality of education and end up being ranked higher, which means they are then perceived as being “better.”

Another major trap students and parents fall into, perhaps partially because of the ranking system, is the association of the students in a school and the school’s worth. Seeing that students graduating from Harvard or Yale are strong thinkers or great innovators, they assume that the colleges themselves offer the best education. In reality, this is because the students that these schools accept are already motivated and overachieving; it’s the students that create this outcome, not necessarily the education they receive. This is called selection bias, and it’s nothing new. It’s akin to how one might assume that the National Basketball Association molds superstar basketball players, when the players were only selected in the first place because of their inherent talent and work ethic. The experience itself doesn’t make them extraordinary, but rather the honor of being selected.

Selection bias also spills into how much money students make after college. Seeing that students who graduate from selective schools earn more isn’t necessarily an indicator of these institutions’ quality of education, given that many of the students admitted to these colleges are wealthy even before setting foot on campus. In a survey sent to the class of 2025 by “The Crimson,” Harvard University’s student newspaper, about 45.1% of respondents reported that their parents make a combined annual income of over $125,000, a figure much greater than the median U.S. income of $67,521, according to the 2020 U.S. Census. As journalist Paul Tough puts it, “elite college campuses are almost entirely populated by the students who benefit the least from the education they receive there: the ones who were already wealthy when they arrived on campus.”

Students might assume, nevertheless, that “elite” schools offer the only opportunity for low-income students to succeed financially later on in life. However, these pillars of prestige and reputation aren’t the only options for students seeking upwards mobility. Schools such as the California State University system and the City University of New York (CUNY) system have proven time and time again to be excellent for students seeking upwards mobility, mostly because they accept more low-income students in the first place. According to a 2017 study led by economist Raj Chetty, CUNY moves six times as many low-income students to the middle class than all of the Ivy League schools (as well as some non-Ivy elites such as Stanford University) combined.

This begs the question: what exactly does measure the worth of a college, if selectivity doesn’t? Of course, there’s no one factor that can measure the value of a university—every student is different, and each needs to look for something different in a college (another flaw of the rankings system). What students can consider, then, is their own path. Instead of defining worth on some obscure standard, they can define it on their own. What matters most to them? Which colleges are best financially? Which are larger? Closer to home? These are just a few examples of the plethora of factors to consider other than prestige, selectivity and rankings.

That being said, it’s important to acknowledge that students’ obsession with selectivity and prestige has created a self-fulfilling prophecy. After all, if we as a community value brand names, then so will our employers, our parents and our friends. The only way to end this cycle is to collectively shift our mindset—which is no easy feat. To start reaching this goal, it’s necessary for students to try to “put their blinders on” and focus on themselves, their passions and their goals, rather than what those around them determine to be the arbiters of success. This doesn’t mean tuning out others’ experiences and advice, or looking down on what factors others use to determine their needs—it simply entails a deeper self-evaluation of one’s goals and values. In this way, students can find the college that best prepares them for whatever path in life they want to pursue. Focusing on narrow and, ultimately, subjective measures such as prestige, selectivity or reputation won’t get students anywhere; it’s best for them to focus on criteria that give true insight into what a college can offer.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Henry M. Gunn High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Senior Amann Mahajan is the editor-in-chief of The Oracle and has been on staff since January 2022. When she’s not reporting, she enjoys solving crosswords,...