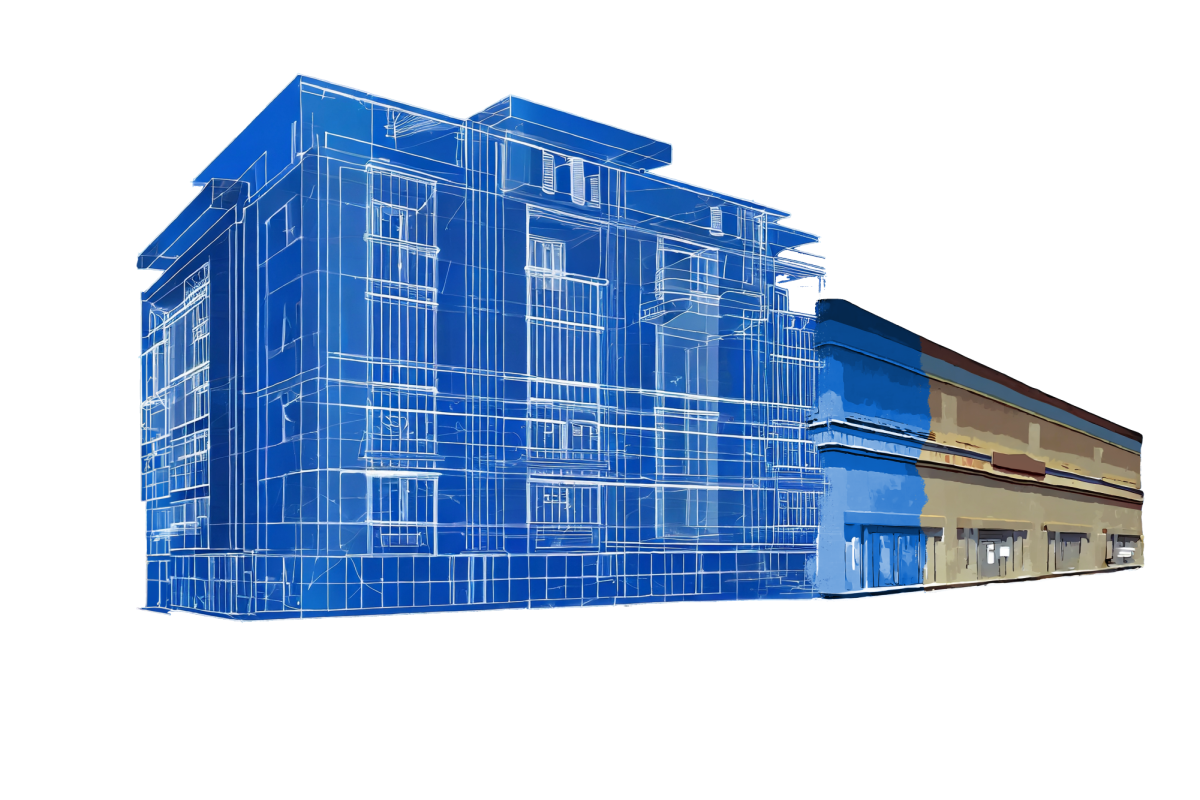

In 1897, 8-year-old Thomas Foon Chew immigrated to a California ridden with anti-Chinese discrimination and violence. Yet, amid this adversity, Chew became one of the wealthiest Chinese Americans in the state, expanding his father’s canning business into the third- largest in the nation. The Palo Alto location of Chew’s Bayside Canning Company — a building on Portage Avenue right off of El Camino Real — was cast back into the local spotlight in late 2020 when its owner, the Sobrato Corporation, announced its plans to redevelop the site and demolish 40% of the cannery in the process. Despite heavy petitioning from local residents and even Chew’s grandchildren, the city approved the plan on Sept. 12.

This story, exemplifying the struggle between efforts for commercial development and cultural preservation, is not unique to Palo Alto — it is happening all around the world because of rapid economic growth and commercialization. Yet it is in citizens’ and policymakers’ best interests to prioritize preserving historical and cultural sites, which hold educational and economic value.

According to Palo Alto Online, as part of the agreement, Sobrato will donate $1 million to city park improvements and $4 million to the city’s affordable housing fund, repurpose a portion of the land along Matadero Creek into a public park, and create 74 affordable townhouses, all while keeping the iconic monitor roofs of the cannery. Still, most of the cannery will be gone as a result of this redevelopment.

Much of history is lost over time. There undoubtedly once existed people and civilizations of which current generations have no awareness. Yet, in addition to records and documents, physical structures provide a significant piece of historical knowledge: According to research by Greene et al. in the Education Next Journal, students who participate in field trips improve their critical thinking and increase their cultural exposure. Sites that have managed to stand the test of time, therefore, are extremely valuable — they furnish opportunities for historical and archaeological study and for society to see and touch history. While the Bayside Canning Company’s Palo Alto site seems insignificantly old when compared to sites such as the Jamestown Colony ruins or the New Mexico pueblos, it too is important: Chew’s success story as an early Asian American immigrant is unique, and it provides a valuable example of persistence in the face of adversity.

Preserving cultural sites also carries economic merits through stimulating tourism. Hearst Castle, a famous mansion built in 1919 in San Simeon, California, typifies this trend: After its owner’s death, the castle and its surrounding property were passed on to the State of California, and since 1958, it has been one of the most-visited parks in the state. According to a 2022 report by the Los Angeles Times, the park’s revenues amounted to $16.2 million in 2019 alone. While Hearst Castle may be an outlier in terms of its popularity and resulting revenue, many examples of smaller profit-operating cultural sites exist. Especially in smaller, mainly residential cities, these sites can draw in vital economic traffic: For example, thousands of tourists travel to small Charlottesville, Virginia, each year to tour Monticello, Thomas Jefferson’s former home and plantation.

Some who favor development over preservation of cultural and historical sites argue that the desired replacements — usually housing or retail spaces — provide access to far more lucrative markets. According to TeamCalifornia, a nonprofit promoting business development, the California retail market pulls in nearly $573 billion annually. This, when compared to the $90 million annual revenue of California historical sites per Statista, presents development as the obvious economic choice.

Others may also claim that these sites are not necessities. Indeed, development paves way for commercial space such as supermarkets or clothing companies, whose products play a more prominent role in everyday life than, say, museums. Replacing these sites with housing renders an even more essential service — according to California’s Department of Housing and Community website, California residents face a significant housing shortage. Still, though preserving cultural sites like the Palo Alto Bayside Cannery may stand in the way of some development projects, the remaining cultural sites only make up a small portion of potential commercial spaces.

While it is now inevitable that a significant portion of Chew’s cannery will be lost, there are still hundreds, if not thousands, of buildings, nature spaces and districts that require community support to guarantee preservation. In 2021 alone, the U.S. National Register registered over 900 new protected sites. Stories like Chew’s are worth saving for future generations to experience — it will be up to everyday people to give them a voice, through lobbying, donating, visiting or simply advocating.