“The odds of recovery are against you,” said a former Gunn student, who wished to remain anonymous. “It kills you and everything around you. It’s such a black hole, and it’s hard to find any way out of that. Most people don’t make it to the decision of recovery before they’re in jail or dead.”

The former student was diagnosed with substance use disorder — specifically alcohol use disorder — as a sophomore at Gunn. After they completed a rehabilitative inpatient program, they transferred out of Gunn and are currently in early sustained remission. According to the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision,” a patient is in early sustained remission if, within a year, they have not had symptoms of alcohol use disorder other than the urge to drink alcohol.

Throughout their years at Gunn, the former student struggled with the early stages of their addiction, which gave way to active addiction, or active substance use disorder, defined by the DSM-5-TR as “patterns of symptoms caused by using a substance that an individual continues taking despite its negative effects.” “People who aren’t affected by substance use disorder — people who aren’t addicts — are going to break their heads trying to understand what it’s like,” they said.

To many, “Don’t do drugs” sounds simple enough — it’s as easy as just saying no. Students are often taught the street names and psychological and physiological effects of various substances in middle school so they know exactly what to avoid and why. They encounter YouTube thumbnails with jarring before-and-after images of heroin addicts. These scare tactics should discourage young adults from future drug use, but ultimately don’t: An anonymous Paly senior who also struggled with alcohol use disorder emphasizes that addiction is often unexpected, and not a conscious choice. “People think it’s the life someone wanted to live, but it’s not,” they said.

The stakes of substance abuse disorder have become especially clear in recent years. According to the California Department of Education, fentanyl deaths accounted for more than 80% of all drug-related deaths among California’s youth in 2021, and the annual crude mortality rate for opioid overdoses in Santa Clara County in 2021 increased by 73% from 2019. In response, PAUSD has implemented staff opioid trainings and fentanyl overdose prevention and harm reduction strategies. Although the district doesn’t condone substance use, its response reflects knowledge of student use, according to Assistant Principal Harvey Newland. “It’s naïve to assume that students do not engage in any substance use over the course of their time at Gunn,” he said.

The American Addiction Centers cite “proximity to substances” as a risk factor for addiction, alongside aggressive behavior in childhood, parental neglect, poverty and peer pressure. However, the Paly senior says it’s not that simple. “A lot of people who use substances never become addicted,” they said. “You don’t know you’re going to be an addict until you are an addict.”

After completing a recovery program in an inpatient treatment center this past summer, the Paly senior is now five months sober. “I have a good set of therapists, my parents have been supportive and my friends have been supportive,” they said. “But at the end of the day, sobriety is one of those things where it has to come from within. Nobody can force anyone else to get sober.”

Mental health complexities

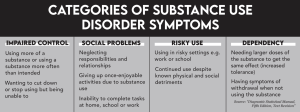

Many explanations of addiction fail to address it with appropriate complexity or confuse addiction with misuse. “Substance misuse and irresponsible use of substances is common and well-understood, but treatment for actual substance use disorders is completely misunderstood,” the former Gunn student said. “A lot of high school students misuse substances, but not a lot have substance use disorders, which is why people don’t understand them fully.”

Often, addiction is framed as a result of bad choices. Although the former Gunn student acknowledges the detrimental choices they made while struggling with alcohol use disorder, they explained that such choices were a result of the addiction, not the other way around. “On one hand, I put myself into a spot where I was severely addicted to alcohol, and I could’ve chosen to stop and put actual effort into recovery earlier on,” they said. “It was my fault, but when I was in a state of active addiction, I had no control over myself. I didn’t even know myself. I was barely a person.”

Psychology teacher Warren Collier explains that addiction at its most fundamental level is a product of repeated and regular drug use. “Usually, a person is using some kind of drug to achieve some kind of high or some pleasurable experience, and they enjoy it,” he said. “They go back and try it again because they want more of that experience, and if that happens over a short period of time, they will start to develop a tolerance and use more.”

Many substances, such as opioids, cocaine and nicotine, cause dopamine to flood the brain’s reward pathway. The brain remembers this flood and associates it with the substance. According to Collier, after a significant period of consistent drug use, students’ brains are no longer able to achieve the emotions or high without external assistance — the drug.

The Paly senior’s experiences with alcohol use disorder reflect this phenomenon. “I started drinking because it was a good time,” they said. “It was something to make the bad thoughts go away. Then, it ramped up, and I would think to myself, ‘I can make it more fun if I drink more.’ And that’s when I became dependent on it, so I couldn’t stop having fun, even if I wanted to. And then it stopped being fun.”

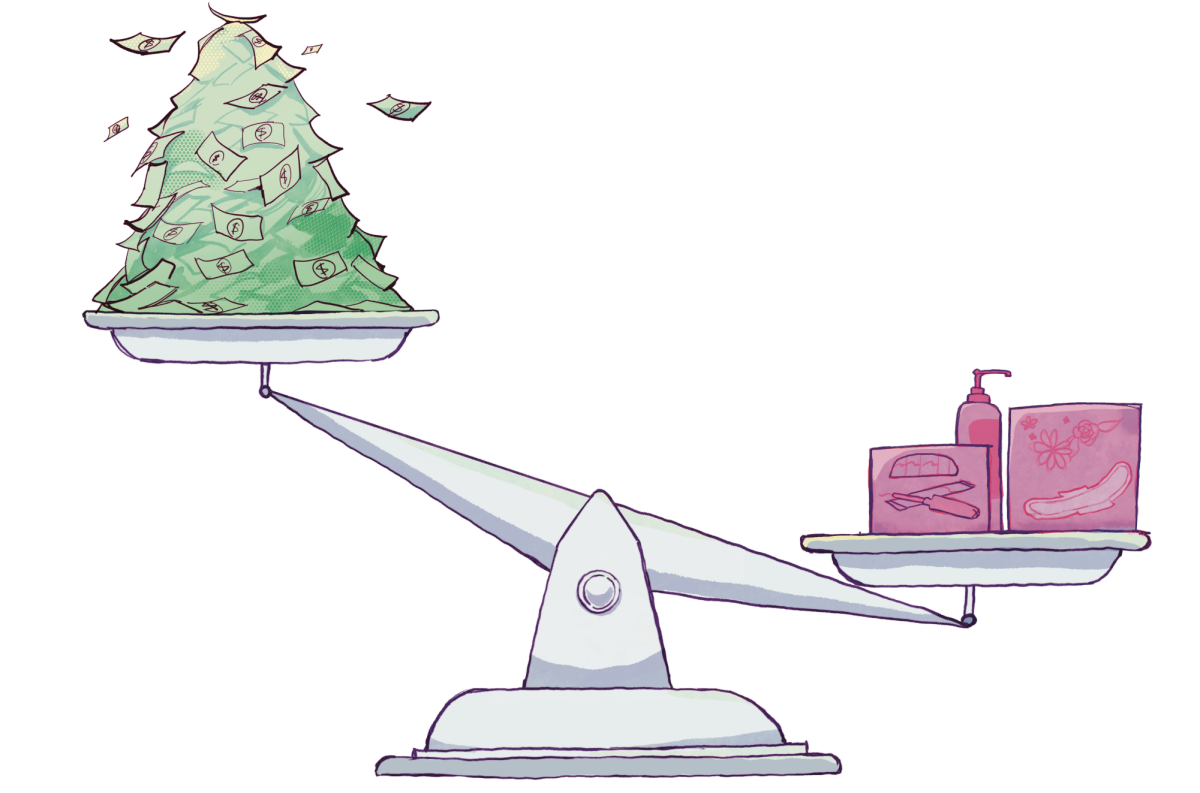

The Paly senior also began using cocaine at the end of their sophomore year. What began as an experiment with some friends turned into addiction. “I was spending a couple hundred dollars a week on it,” they said. “I accidentally detoxed at work one time because I miscalculated how much coke I had that day. I was throwing up in the bathroom at work. And after that day, I said, ‘Screw this. I can’t do it anymore.’ So I told my friends, ‘You need to keep me in check, I’m not doing this anymore.’”

Individuals are sometimes able to pull themselves out of addiction on their first try. Sometimes, they aren’t. The former Gunn student went to an inpatient rehabilitation center twice before exiting active addiction. Either way, both the Paly senior and the former Gunn student were supported by empathetic people around them who encouraged them on their distinctive paths to recovery.

Sometimes, mental-health struggles can lead to substance abuse. The Paly senior explains that their addiction developed partially due to depression. “I didn’t think I was going to have a future,” they said. “If you want to have the best year of your life and nothing past that, you should do a whole bunch of drugs. But if you want more than a year — you want a life — then drugs aren’t an option.”

The former Gunn student used substances as a coping mechanism for mental-health struggles as well. “I was at the worst point in my life with my mental health, and I found that being intoxicated distracted me from the reality of my situation,” they said.

A 2005 research paper published in the National Library of Medicine explored the comorbidity of substance use disorder and mood disorders. The researchers ultimately pointed to psychiatric treatment, which tackles both substance use disorder alongside the mental health issues that commonly occur simultaneously or are the root cause of addiction. “Nobody says they’re going to be an addict for fun,” the former Gunn student said. “Usually, they have an outside problem that they want to cover up. A lot of people’s way of coping is with drugs.”

Supporting students

According to Newland, the Gunn administration has no standardized protocol for supporting students with substance use disorder. In general, administrators first try to holistically assess the student’s situation and the factors contributing to their substance use through a Student Success Team meeting involving families, counselors, administrators and teachers. “It’s really up to them in terms of what they want to share with us,” Newland said. “We need to work with whatever we are given and come up with support and resources that we can provide.”

He explained, however, that situations which place students in urgent harm must be dealt with immediately under mandated-reporting rules for staff. “If something comes up that falls under the guidelines set for Gunn teachers and administrators, we have to report it and follow that exact protocol,” he said. “Administrators are not required to intervene beyond the protocol.”

The former Gunn student noted that, in their case, these protocols were not always helpful. “I appreciate that (Gunn administration) has been understanding and tried to see it as a mental health condition,” they said. “But aside from one counselor, I have not received any support or outreach from them — not when I was in active addiction, nor when I came back from rehab.”

The severity of addiction also informs staff response. “Are you calling paramedics?” Newland said. “How immediate is the situation? Those types of questions guide us in how we provide resources and move forward in supporting the student.”

Na

Regardless of the level of severity of a student’s substance use, both the Paly senior and the former Gunn student believe that schools should intervene with empathy. “I was lucky to have that one counselor who really empathized with me,” the former Gunn student said. “He was in contact with my (parents) a lot and understood the mental health aspect of (addiction). But if he wasn’t there and the Gunn administration didn’t have his input, I think the administration would’ve thought I was just a lost cause.”

Sometimes, this means repeated check-ins with students. “If someone was caught with a (wax) pen in their hand, the administration would confiscate it, send a letter home and maybe enforce disciplinary action,” the former Gunn student said. “But also make them meet with the counselor. Make them meet with one of the school therapists. (Students) should be able to see that it’s not normal to feel the need to be intoxicated at 11 a.m. More times than not, substance use is about mental health.”

According to the Wellness Outreach Worker Rossana Castillo, the Wellness Team’s first step when supporting a student suffering from addiction is to identify the origin of their substance abuse, whether it’s emotional or mental. While Gunn Wellness can provide immediate and short-term support, in situations where students require specialized treatment, the team works to connect the student and their family to long-term specialized resources.

The Wellness Team also highly encourages students to notify the wellness staff or any trusted adult when a friend may be struggling with substance abuse disorder. They will connect the struggling student to resources as well as connect with their friend to ensure that they don’t carry the load of supporting their friend on their own.