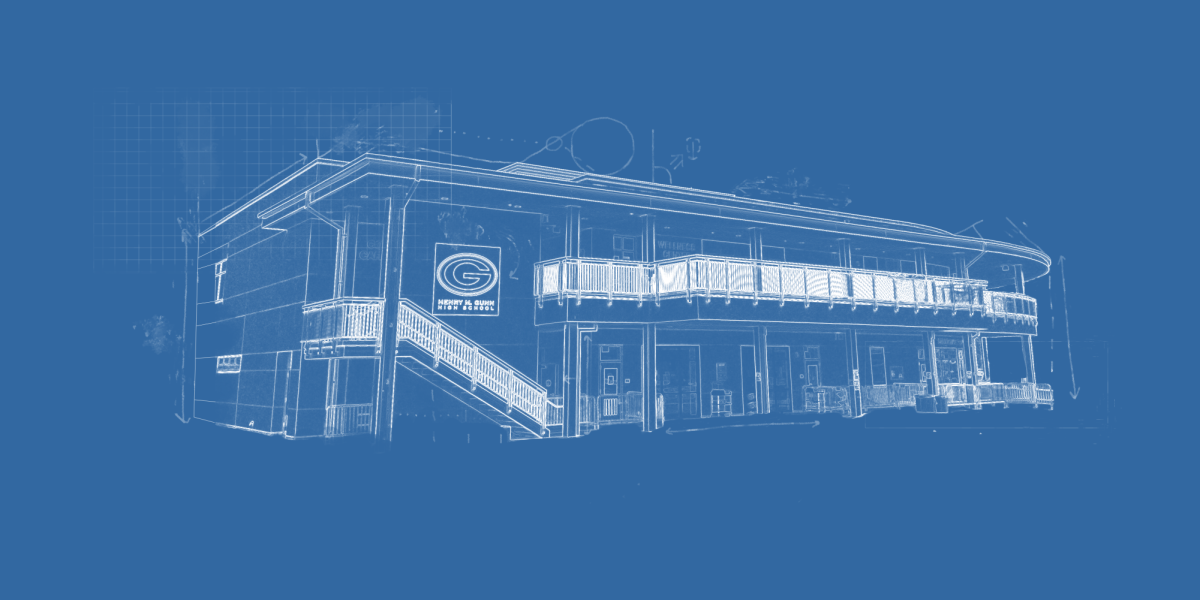

On Jan. 30, PAUSD Assistant Superintendent of Secondary Education Dr. Guillermo Lopez moderated the second ethnic studies community meeting alongside Gunn and Paly teachers on the district’s Ethnic Studies Committee.

Although the virtual meeting was advertised as a “community input session,” per Superintendent Dr. Don Austin’s Jan. 26 Superintendent’s Update, many questions in the Zoom chat — where participants were directed to ask their questions — remained unanswered.

Instead, toward the end of the meeting, which ended 15 minutes earlier than scheduled, community members could fill out a form with any remaining questions. When a similar form was sent out last December, however, parent of PAUSD alumni Lori Meyers emphasized the difficulty of giving specific feedback, as the substance of the course’s units and lesson plans wasn’t included.

“The community in general, and myself included, found it really difficult to understand exactly what we were giving feedback on, because it was something like, ‘What is your feedback on the section titled “Identity?”’” Meyers said. “We were like, ‘We don’t have any information’ — (the form) didn’t give us any real content to delve into.”

In a follow-up conversation with The Oracle, Lopez said that responses to questions asked on the form would be posted to the district’s ethnic studies webpage in the near future, but wasn’t able to provide a firm date.

The Jan. 30 meeting was one of many instances in which community members raised questions about PAUSD’s new ethnic studies class. Passed in October 2021, California’s A.B. 101 mandates an ethnic studies-course graduation requirement for all public and charter high schools. The requirement aims to acknowledge the state’s diverse population in its curriculum, and follows research co-authored by Stanford Graduate School of Education professor Thomas Dee in 2021 demonstrating ethnic studies’ positive impact on attendance and graduation rates for ninth-grade students.

In PAUSD, freshmen will first take a semesterlong ethnic studies course — which aims to “examine California as a microcosm of the United States and focus on themes of social justice, social responsibility, and social change by increasing student agency” — before covering world history in the second semesters of ninth and 10th grade.

While ethnic studies has long been a contentious matter, tensions have risen since the onset of the Israel-Hamas war on Oct. 7, with educators, parents and students attempting to reconcile their ideas for the content and structure and content of the course.

Path to a state mandate

On Nov. 6, 1968, the Black Student Union and Third World Liberation Front, a coalition of ethnic student organizations, went on strike at San Francisco State University (then San Francisco State College) to advocate for more diversity in the admissions process and for the creation of a school of ethnic studies. After more than four months of striking, San Francisco State established the nation’s first College of Ethnic Studies, which began operating in fall 1969.

Though it remains one of the only institutions of its kind in the U.S., ethnic studies courses have since become more common at other colleges and universities.

Five years prior to A.B. 101, former California Gov. Jerry Brown signed A.B. 2016 into law on Sept. 13, 2016, mandating the Instructional Quality Commission to develop an ethnic studies model curriculum for high schools. When the commission completed their first draft, however, it faced backlash for being ideologically left-leaning and excluding certain topics, such as antisemitism. On Aug. 12, 2019, California Board of Education President Linda Darling-Hammond announced that the Instructional Quality Commission would be submitting a new draft to the Board for approval.

“Ethnic studies can be an important tool to improve school climate and increase our understanding of one another,” she wrote in a press release. “A model curriculum should be accurate, free of bias, appropriate for all learners in our diverse state, and align with Governor Newsom’s vision of a California for all. The current draft model curriculum falls short and needs to be substantially redesigned.”

After three additional drafts, on March 18, 2021, the California Board of Education adopted a 688-page model curriculum. Although the course’s primary focus remained on African Americans, Asian Americans, Latino Americans and Native Americans — the groups most college ethnic studies courses center around — the model curriculum expanded to include lessons on other ethnic groups in the U.S. Furthermore, the final draft included guidance to teachers on establishing trust when discussing complex topics and presenting balanced coverage of issues.

Current concerns

Some on the commission, however, were dissatisfied with the final model curriculum. A September 2023 letter from the University of California Ethnic Studies Faculty Council expressed concerns over the weaponization of “guardrails,” which preclude ethnic studies from promoting any discrimination, bias or bigotry.

The first draft of the state model curriculum included lesson outlines on the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement against Israel and studies of figures such as U.S. Reps. Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib, whom some have criticized for anti-Israel comments. The final version does not include these lessons, instead focusing on the history and contributions of Arab American communities, as well as common stereotypes that Arab Americans encounter.

The 2023 letter contended that restricting certain material from the curriculum mirrors “conservative efforts in states such as Texas and Florida to suppress hard truths about racism and colonialism” and that “California teachers should be able to deliver lessons on important concepts such as settler colonialism, apartheid, and resistance without having to fear censorship or legal action by the state.”

Those with similar views joined to create the Liberated Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum Consortium, which first convened in April 2020. The organization has their own model curriculum that aims to have students look through the “intersectional lenses of race, ethnicity, culture, gender, sexuality, ability, language, immigrant status, and class” and “analyze indigeneity, white supremacy, oppression, privilege, and decolonization, and work toward empowering themselves as anti-racist leaders who engage in social justice activism.”

Many, including former California State Superintendent of Public Instruction Bill Honig, have urged schools to reject the “liberated” curriculum in favor of the state’s model, noting the dangers of using group identity as the primary lens to examine history, society, culture and politics. On the other hand, proponents of the “liberated” curriculum argue that de-emphasizing systems of power and oppression detracts from ethnic studies’ original purpose, leading to surface-level, non-critical explorations of culture and race.

According to Lopez, PAUSD has partnered with the University of California, Berkeley’s High School Ethnic Studies Initiative — part of its History-Social Science Project — starting this year. Some community members have expressed concerns about this partnership, as the group lists the Liberated Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum as a teaching tool and also worked with the Oakland Unified School District, in which a faction of the Oakland Education Association participated in an unauthorized pro-Palestinian “teach-in.”

In a Jan. 19 email obtained by The Oracle through the California Public Records Act, Austin clarified to the PAUSD Board of Education that the Oakland teachers union failed to follow standard processes and taught lessons that weren’t connected to the Berkeley consultants.

“During the (curriculum development) process we will consult with a lot of people,” he wrote. “That should be what is expected. There will be many efforts to silence voices, starting with who we even speak with. I am asking that we continue to share the process and timelines and that our board helps people who reach out to understand that we have identified input opportunities.”

In PAUSD, Gunn Social Studies Instructional Lead Jeff Patrick said that though some lesson outlines from the state’s model curriculum may be used, most would be generated by Gunn and Paly teachers. He also noted in an email that it would be “extremely unlikely that (the district) would use anything specific from the Liberated Ethnic Studies group.”

Community feedback

In order to prepare for the 2025-26 course rollout — which was pushed back one year to allow for further course development — PAUSD formed its Ethnic Studies Committee last school year, comprising Lopez, Patrick, Paly Social Studies Instructional Lead Mary Sano, and other Gunn and Paly teachers.

The committee is currently refining the course’s five core units: Identity; Race and Ethnicity; History and Migration; Language, Culture, Education, and Learning; and Action and Civic Engagement. It is also soliciting feedback from students and community members. At the Jan. 30 meeting, the committee announced a new Unit 0: “Why Ethnic Studies?,” and Lopez noted the possibility of one section of ethnic studies running at each high school next school year to allow for additional fine-tuning before the final rollout.

Thus far, alongside the two community meetings, Paly and Gunn held information and student-feedback sessions during PRIME on Oct. 11 and Oct. 18, respectively.

At the school-board level, community members have advocated for an ethnic studies course encompassing more ethnic groups — mirroring the activism that led to the state’s sprawling model curriculum.

During Open Forum on Nov. 14, 2023, 17 Middle Eastern and North African community members spoke about their experiences with Islamophobia and advocated for MENA inclusion in ethnic studies. According to Paly senior Mariam Tayebi, who is the MENA Club co-president, the group felt compelled to speak after facing bullying and discrimination following the start of the Israel-Hamas war.

“We decided that it’s really important for us to show the district and show whoever else watches (the Board meetings) that there are kids here and we are struggling and we want to be represented,” she said.

At the next meeting, on Dec. 12, eight Jewish parents and students — including PAUSD parent Linor Levav — detailed personal experiences of antisemitism and asked for Jewish voices to be included in the ethnic studies curriculum. Although Jewish Americans’ history is typically not covered in most college-level ethnic studies courses — they are considered white in the context of the discipline — the California model curriculum includes lessons on Jewish Americans and antisemitism.

“I want to ask you to please include Jewish Americans in our ethnic studies class,” Levav said during Open Forum. “Antisemitism has exploded across the United States and the Bay Area. It’s fueled by lies about Jews and Israel. PAUSD can and should help to correct this.”

Beyond specific ethnic-group considerations, many have advocated for transparency with the curriculum-development process.

“It’s very, very important that there is … full transparency,” Meyers said. “The more that the community and students and parents can see what’s going on in ethnic studies, the better and smoother the process is going to be, and the more likely it’s going to be that we get the kind of ethnic studies class that I think we all really want.”

While Patrick understands the community’s desire to participate and the need for PAUSD to share updates and solicit feedback, he emphasized that the lack of transparency some feel can mostly be attributed to educators’ newness to the process, not ulterior motives.

“What we’re trying to do is create a course that’s going to be best for our students,” he said. “So as people are looking at our work and bringing up their own points, I hope that they can keep that in mind that some of the comments parents make might not be in the best interests of our students as a whole.”

Along a similar vein, though PAUSD parent Uzma Minhas also values transparency and community involvement, she cautions the district from only listening to the loudest and most organized groups.

“They have to be very careful that oftentimes marginalized communities don’t speak up, so they may not be hearing from the most marginalized communities,” she said.

A realistic curriculum

Although much of the conversation surrounding ethnic studies has revolved around Jewish and MENA curricular inclusion, Patrick emphasized that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict would not explicitly be covered in the new course, and that it’s currently a part of the sophomore Contemporary World History class.

“The scope that the state intends for the ethnic studies curriculum is narrower than the general public … is aware of,” he said. “By the time students are there in 10th grade looking at that topic, they will have hopefully developed the skills or began to develop the skills to analyze those things on their own.”

Paly senior Alma Samet — who identifies as a Mizrahi Jew (Jewish people who are of MENA origin) — agrees with this assessment, noting how including the conflict in ethnic studies could exacerbate misrepresentation.

“I really could see it just overriding and taking up a lot more space in the curriculum than it has to, especially when there are so many different topics and communities to focus on,” she said.

Still, senior Deena Abu-Dayeh stressed the imperfections of how the Middle East is currently covered in Contemporary World History, citing her own experiences.

“The only time I’ve ever heard (about) Palestine — which is where I’m from — is when it had to do with the conflict and how we are the terrorists, and that name has been portrayed on us a lot,” she said. “That kind of gives a false image that all of us are just barbarians that have to deal with poverty.”

According to Patrick, the ethnic studies course’s final unit — Action and Civil Engagement — will include a capstone activity allowing students to have more choice in the topics that they delve into.

Looking ahead, the social studies department plans to identify potential ethnic studies teachers by this spring, so that it can spend the next school year in professional development related to the course. Although specific trainings have yet to be finalized, teachers will be focusing on developing common understandings of sociological terms that may not be as prevalent in other history classes, such as “dominant and counter narratives” and “intersectionality.”

Ultimately, despite the complex and often-controversial process, Samet maintains an emphasis on the course’s central objective.

“I think the main goals are just to create more well-rounded, respectful students who are ready to go into a world that is very diverse,” she said. “Especially in America, it’s a big old melting pot, so making sure that people maintain respect for all types of cultures and traditions and also understand a bit more of a backstory on the struggles that these communities have faced.”

The next ethnic studies community meeting will be conducted as a webinar, and the district will ask for questions in advance. More information will be provided in Dr. Austin’s weekly Superintendent Updates.