From Hermione in J.K. Rowling’s “Harry Potter” series to Starr Carter in Angie Thomas’ “The Hate U Give,” empowered women have become increasingly prominent in literature. This development, however, is fairly recent, as women have historically been excluded from creating and starring in narratives.

Traditionally, female narratives center around service, obedience and helplessness. The push for a more diverse, equitable and truthful depiction of women has turned a new page in the history of literature.

Representation in literature depends on representation in authorship. According to a 2023 paper by American economist Joel Waldfogel, in the 19th century, only 10% of books in the Library of Congress had authors with female first names. While this measure does not account for female authors who — like George Eliot — used pseudonyms to disguise their gender, the disparity remains stark: The male-dominated field resulted in books that mostly included male perspectives, in which women were only secondary characters.

These pieces of literature are now part of the American literary canon, which comprises the works deemed highest quality and most important, such as “The Great Gatsby” or “1984.” English teacher Paul Dunlap tries to subvert this trend in his classroom by teaching a mix of canonical works and more female-centric novels.

“What I used to call ‘the canon’ was pretty male-centric and women were peripheral characters,” he said. “I think we’re doing a better job inviting people to read stories that put women as central characters.”

This idea is mirrored in American literary historian Cynthia Griffin Wolff’s “A Mirror for Men: Stereotypes of Women in Literature,” in which she explores themes that seem missing from most historical literature, including motherhood and marriage (or the choice not to), private life, loss of beauty and menopause.

Instead, women are only caretakers — mothers, sisters, wives — or love interests. In Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s “Crime and Punishment,” for example, the female characters all fall under either one of these categories and interact with other characters within the confines of these roles.

More multifaceted and truthful depictions of women started appearing on a larger scale in the 1970s. English teacher Tarn Wilson, who is also a published author, notes that during this time period, a major gender shift in the publishing industry paved the way for better representation of women: According to Waldfogel, the number of female-authored books in the Library of Congress reached 18% by 1960.

Since the early 2000s, books aimed at teenagers have changed dramatically, as have their demands, leading to more accurate characterizations of women. The 2000s saw a revival of the science fiction and fantasy genres in young-adult fiction. These novels included strong-willed, powerful female protagonists.

Published in 2008, Suzanne Collins’ “Hunger Games” trilogy features Katniss Everdeen, a young woman, fighting against an oppressive government. “The Hunger Games” trilogy was an instant hit, initiating a trend of dystopian novels in which women save their worlds, such as the “Divergent” trilogy by Veronica Roth and “Shatter Me” series by Tahereh Mafi.

While these series do contain strong romance arcs, they portray women as more than just caretakers or secondary characters. They are now the protagonists of their own story, making hard decisions and showing an array of emotions.

Senior Fiona Li has seen a growing trend of fleshed-out female characters, with titles such as Alice Walker’s novel “The Color Purple” and Abraham Verghese’s novel “The Covenant of Water” rising to the fore.

“Now, if you look at best-sellers, YA, romance and others, you see a lot of books with female protagonists where it’s based on their life and there’s not as much emphasis on a love story,” Li said.

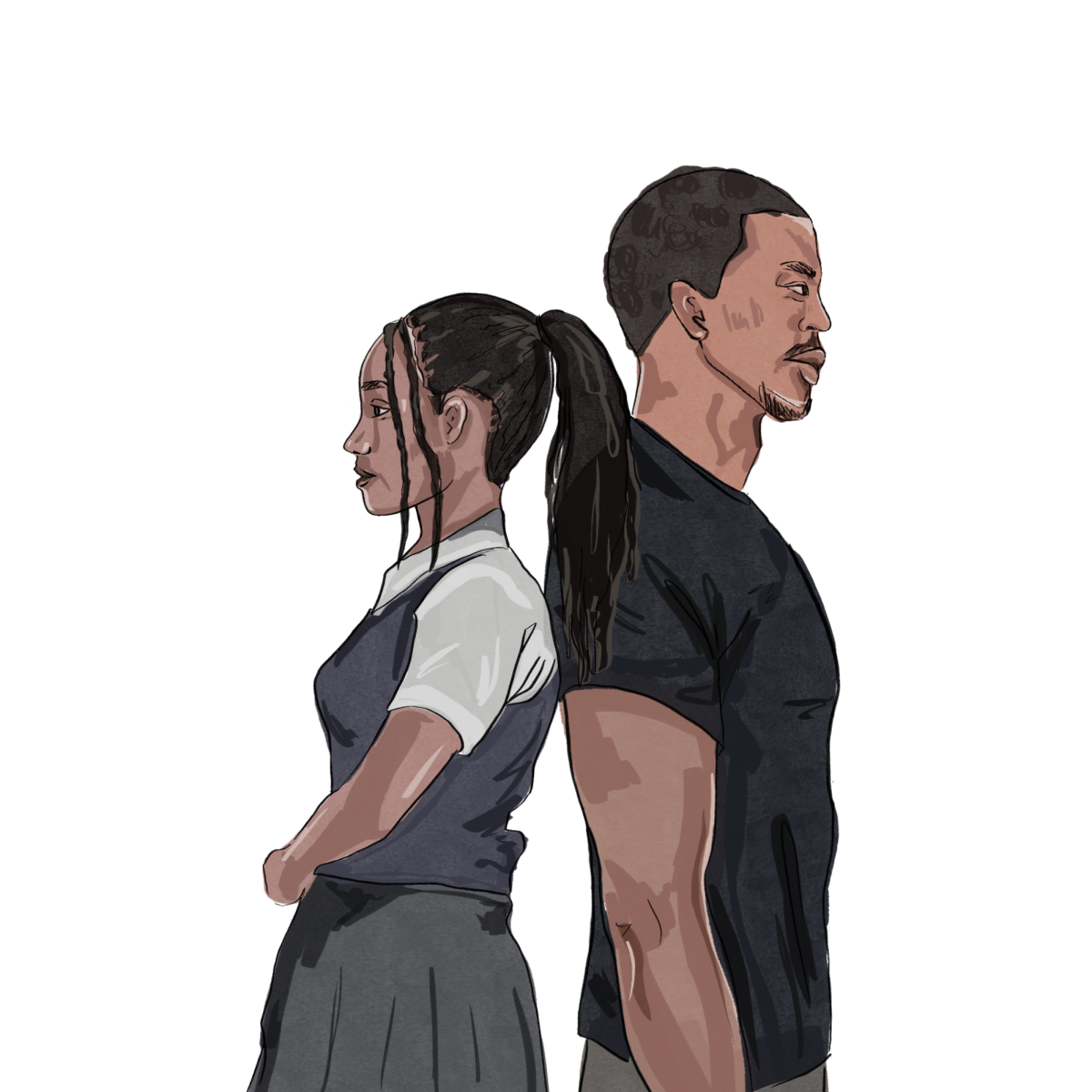

Diversity in literature allows non-women readers to better understand women’s experiences. American author Toni Morrison’s Nobel Prize speech reflects this idea, according to Dunlap.

‘“Tell us what it is to be a woman so that we may know what it is to be a man,’” he said, quoting Morrison’s speech. “We read literature to empathize with other people, and that’s the only way we can learn about others.”