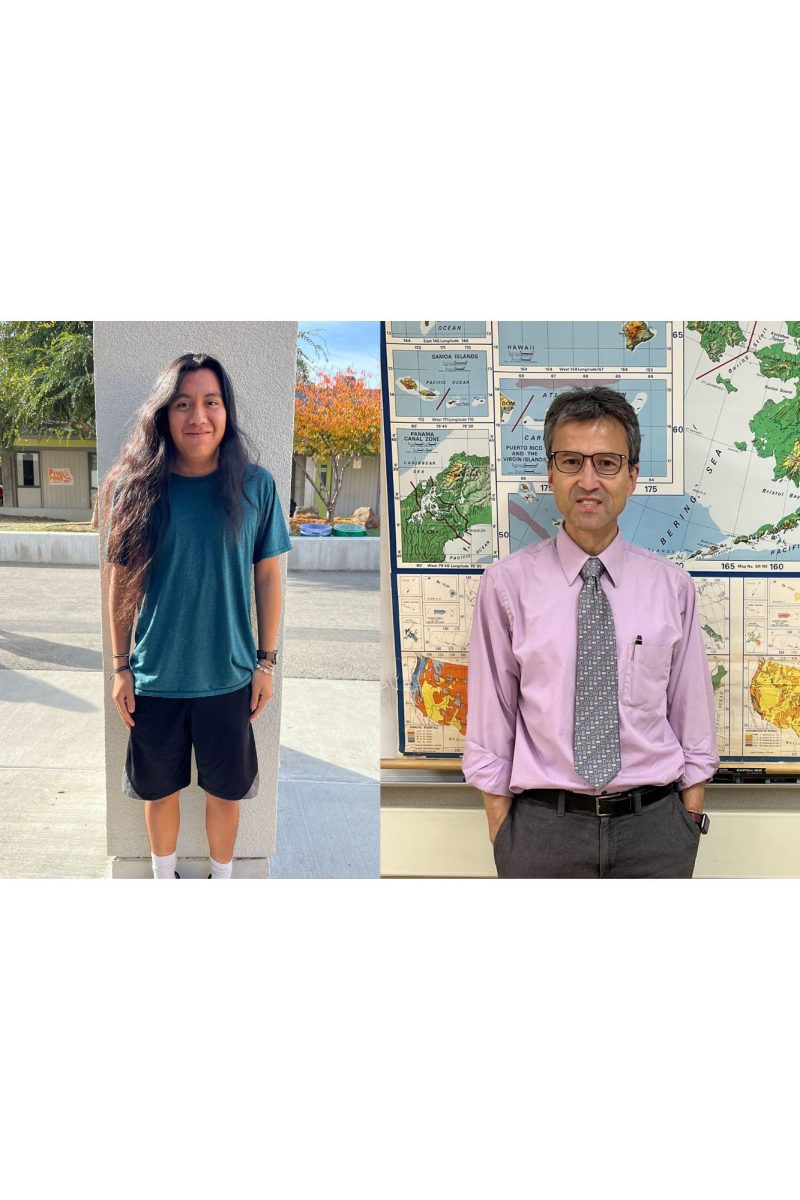

When English teacher Terence Kitada was younger, he witnessed his sister, an avid video game enthusiast, struggle to find acceptance in gaming communities dominated by her male peers.

“(When my sister went) off to college and she was like, ‘Want to play Mario Kart?’ all the boys were surprised,” he said. “They were like, ‘What, you know how to play this? But you’re a girl!’”

This sentiment still persists. Marginalized individuals who play video games in the modern day face toxicity and harassment from other gamers much more frequently than their non-marginalized peers. A 2021 study by the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, an organization that works to reduce negative stereotyping in entertainment and media, found that 50% of gamers between the ages of 16 and 19 witnessed homophobic language while playing video games. Of the same age group, 47% witnessed racist language, 41% reported seeing sexist language and 41% reported ableist language.

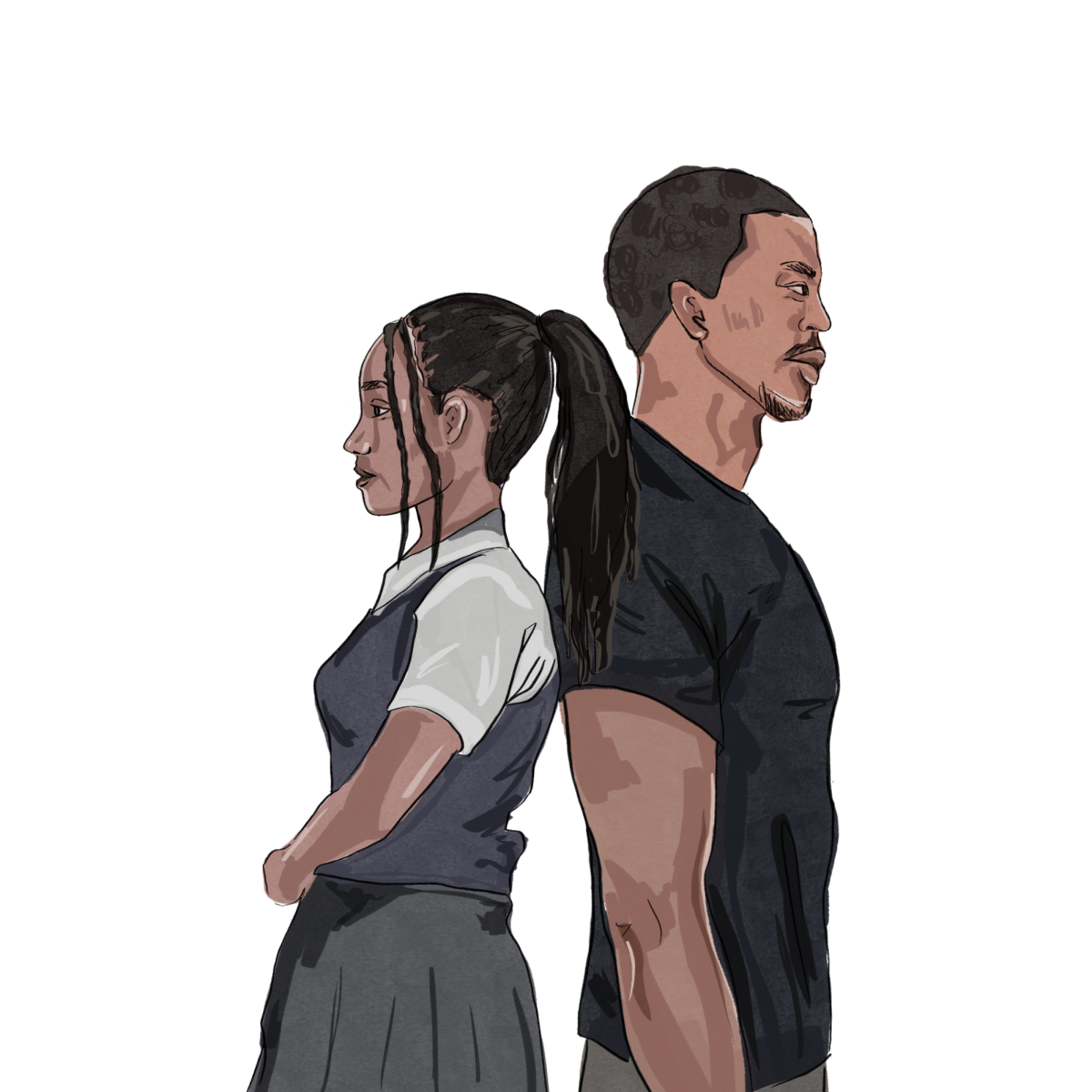

Female gamers today are often forced to guard themselves from sexist and sexual comments from men. According to the 2021 Geena Davis Institute study, men “were found to feel more entitled to express social dominance in the virtual world than in the real world, because men outnumber women in networked video games and masculine behavior is typically rewarded.”

Special Education Instructional Lead and English teacher Briana Gonzalez has been harassed on the basis of her gender by fellow gamers.

“Far Cry: New Dawn had a co-op option that I really enjoyed, and unfortunately I just don’t participate in it anymore, just because the moment they hear my voice, it’s just really inappropriate,” Gonzalez said. “I unfortunately have experienced sexual harassment through online gaming.”

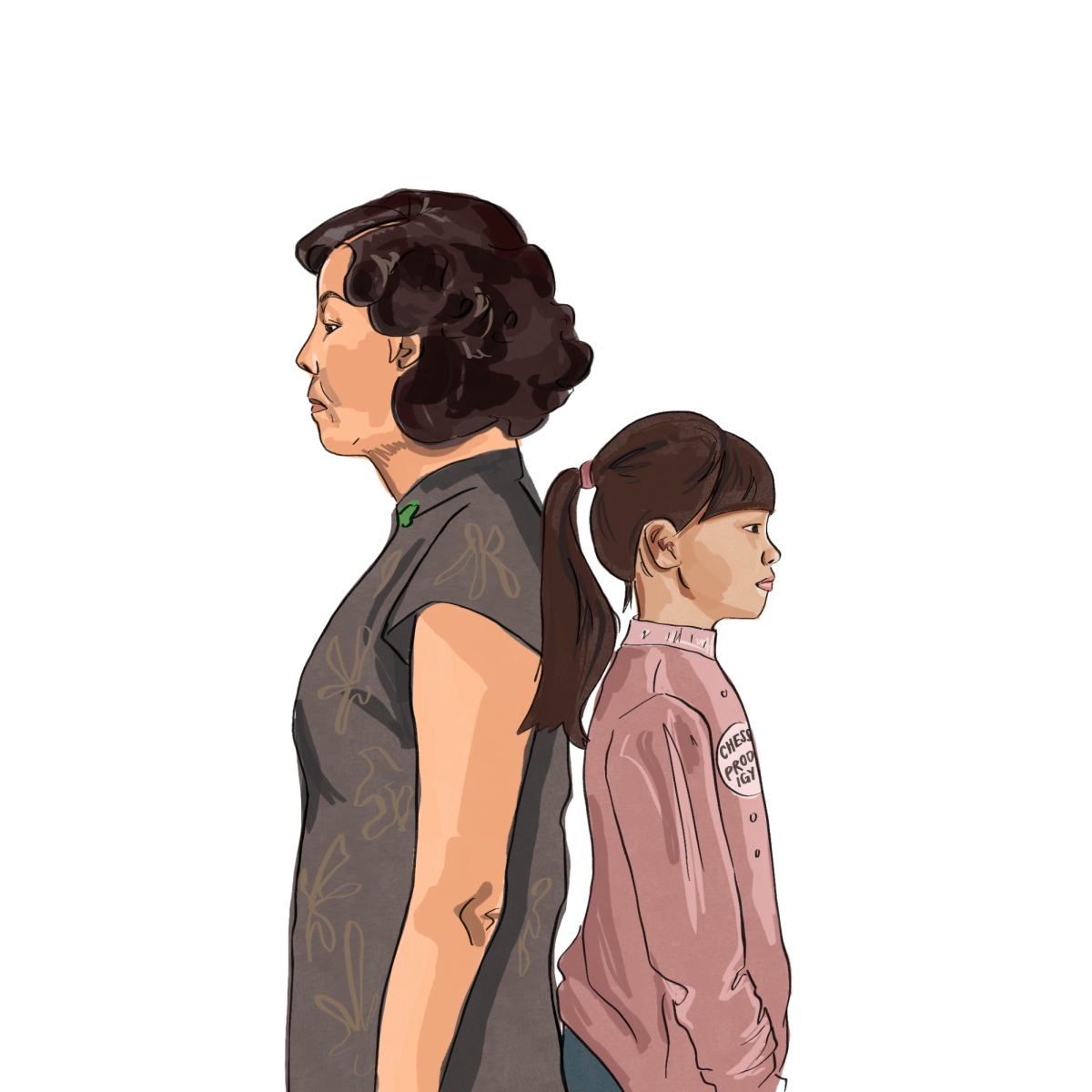

Senior Emma Cao, who is experienced with online gaming, has also found the world of gaming to be dangerous. She takes measures to minimize her chances of being harassed when interacting with other gamers online, though they are not foolproof.

“I protect myself a lot — like I don’t talk when I don’t need to,” she said. “I speak in a lower intonation. It sucks that (harassment) happens. You just have to pray that the loser named CatWoman420 doesn’t choose to hate you.”

Ableist language is also abundant in gaming communities. Senior Vincent Boling, who is autistic, has experienced hostility from other gamers because of his neurodivergence.

“(If) I was trying to communicate with my teammates, and I was maybe a little sloppy, or I was not always picking up on the implications of the signals, then I would definitely get pretty ragged on for that and called a lot of slurs and stuff,” Boling said. “There’s a lot of ignorance surrounding neurodiversity, and they definitely weaponize that.”

According to Kitada, video games’ allowance of anonymity facilitates online misbehavior and harassment.

“If you can’t see the reaction of the person you’re hurting, then it’s the sense of, ‘Oh, I can say whatever I want and just be as mean as I want,’” he said.

Despite the rampant negativity from other gamers, marginalized groups can find safe havens by forming sub-communities with gaming as a mutual interest. Gonzalez was a part of one such group.

“I found a really unique community at my undergrad: other people just like me, other girls also interested in gaming,” she said. “I could talk about Call of Duty: Black Ops, and before, that would never happen.”

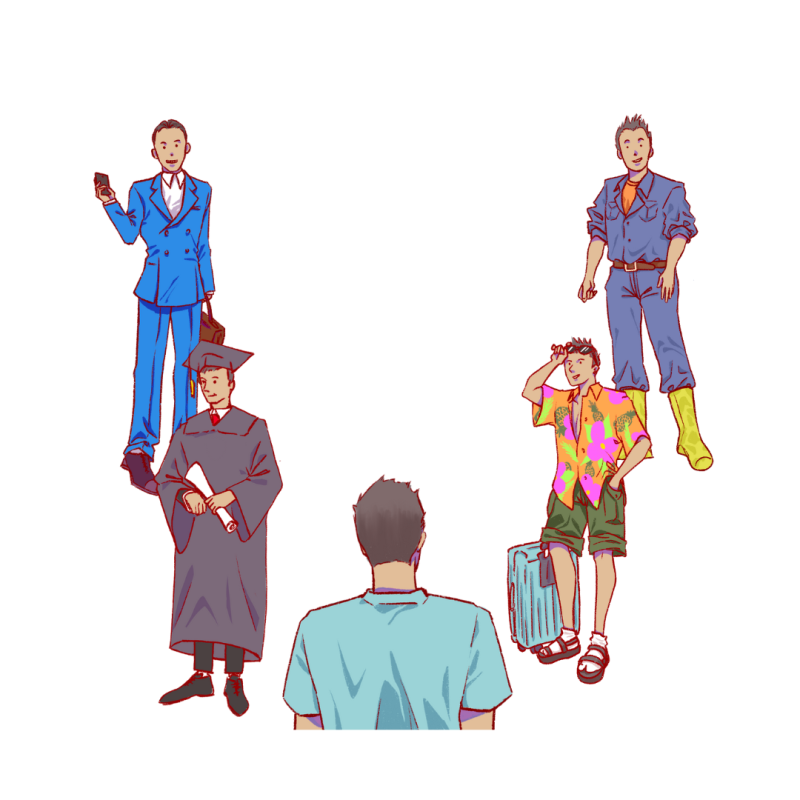

Increasing the diversity of video game characters may also help marginalized gamers feel welcome in online spaces. In many games, character customization options are limited and don’t allow marginalized players to accurately represent themselves in the game.

“Especially if your characters are supposed to serve as your avatar, you’re supposed to create somebody who looks like you, right?” Kitada said. “What are the character creation options, or is it just standard like a bald, young white man? So many FPS (first-person shooter) games have that kind of character who’s the standard avatar. You’re like, ‘That’s not me.’”

One way to improve representation in video games is to introduce more diverse viewpoints into the game development process. The field is currently heavily male and white dominated, with 62% of developers identifying as male and 78% identifying as white, according to the International Game Developers Association 2021 Developer Satisfaction Survey.

“I just feel like companies need to be a part of this (diversification) process and re-evaluate their own culture and their own hiring practices,” Gonzalez said. “Because as long as you’re only hiring a certain group of people, that’s the content you’re gonna get in turn.”

According to Boling, harmful comments online often come from miseducation rather than malice. As such, these instances of bullying can be sometimes leveraged as opportunities for growth.

“A medium like a video game where you’re cooperating is a good time for people to learn and grow,” Boling said. “A lot of gamers are stubborn and old and terrible, but most of them aren’t. Most of them are just kind of cranky, but are genuinely willing to listen.”