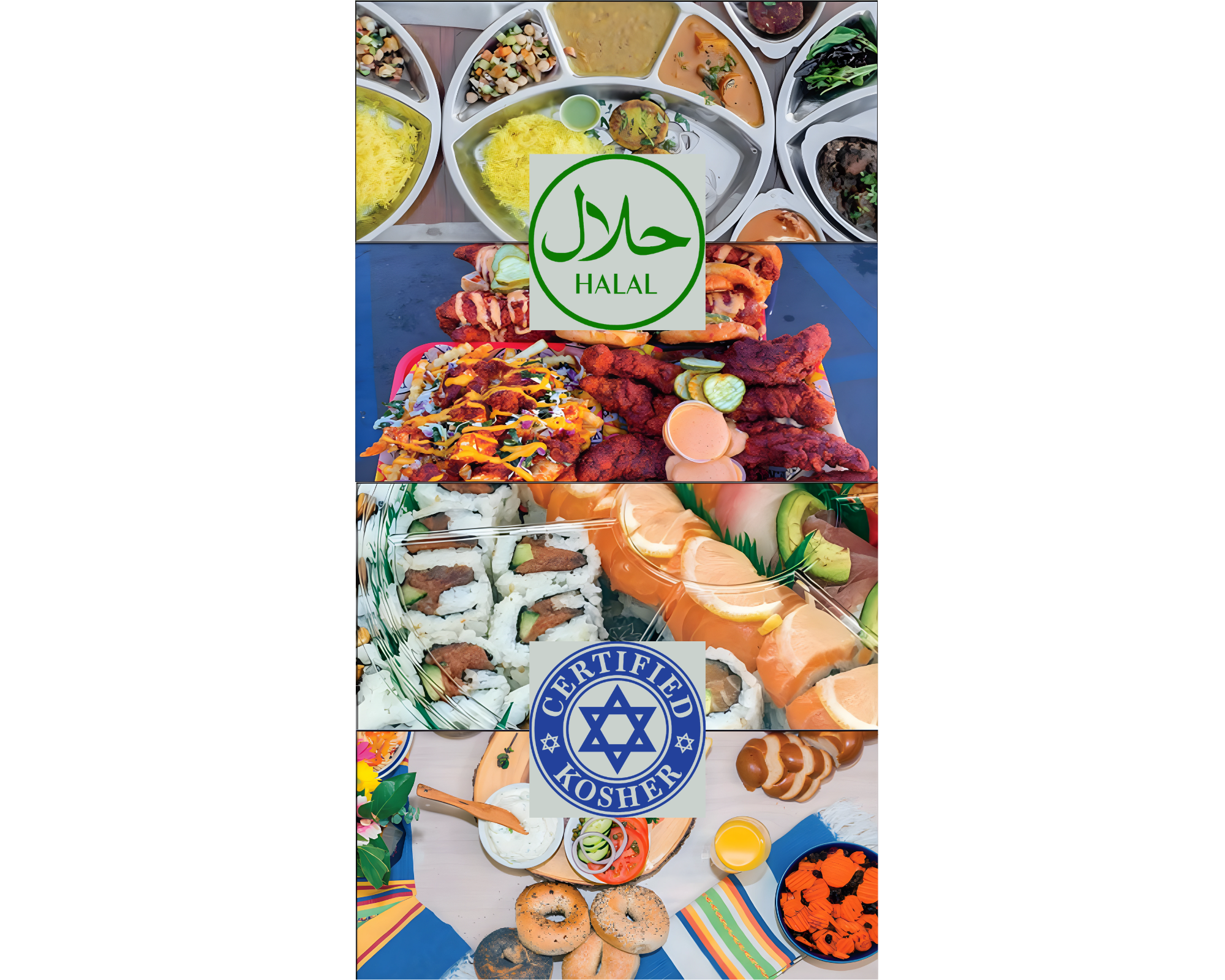

Halal, kosher values govern food, social interactions

Senior Yahya Mirza stared down the track. He had not had any food or water in over 12 hours because he was fasting for Ramadan, and he was about to run a 400-meter race. Fatigue and weakness weighed him down as he took his place on a lane, anticipating the painstaking race before him.

Nevertheless, he made it through. After finishing the track meet, Mirza was physically drained, but his spirits were lifted.

“I realized that there are many other people who do (track) while fasting,” he said. “It gave me a new appreciation for the mental strength involved in the halal lifestyle.”

Mirza is one of many Muslims who partake in a halal lifestyle. This lifestyle is based on the concepts of “halal” (allowed or permissible) and “haram” (forbidden), which are taught in the Quran, the sacred scripture of Islam. The natural state of everything is halal, and things are haram only if specified in the Quran — pork, for example, is haram because pigs are considered unclean. These concepts apply to aspects of life beyond food, including social norms and individual beliefs.

“Universally, (the halal lifestyle) is no pork, no alcohol, no drugs,” Mirza said. “But there’s more to it with the halal lifestyle. I see the halal lifestyle as my moral code, along with the Islamic moral code.”

Freshman Hana Siddeek, who is also Muslim, noted that the distinctions between haram and halal aren’t always simple.

“There’s some circumstances nowadays where there’s not something specifically stated, so you have to use logic and reason and the sayings of the Prophet, peace be upon him, to infer the right decision,” she said. “There’s also varying degrees of disliked, allowed, permissible and encouraged.”

The strictness with which the lifestyle is followed also varies. Siddeek and her family are flexible with some things because of their personal beliefs and choices.

“Gelatine is sometimes taken from the insides of a pig, so a lot of Muslims won’t eat gelatine unless it’s halal gelatine,” she said. “But my parents (took) a class and their teacher told them that gelatine is chemically reformed — it’s a completely different thing and not actually pork. So, I eat gelatine.”

Nevertheless, finding food options can be difficult. Students may opt for vegetarian options simply because finding halal-certified food options can be challenging. While Mirza has faced these difficulties, he also noted that those at Gunn do their best to make allowances.

“You can’t necessarily eat (school lunch) depending on which family you’re from,” Mirza said. “People (at Gunn) are supportive and they understand the restrictions that I have. I feel like Gunn makes the halal lifestyle relatively easy.”

Outside the realm of food, haram and halal also govern other aspects of daily life, including social interactions.

“I can hang out with my friends just fine, but if my friends are making bets or playing poker, I just don’t put any money in,” Mirza said. “(Living halal) also teaches me how to create my own boundaries so people don’t cross them.”

For Siddeek, part of living halal is not dating.

“I don’t date,” she said. “This is a reason why I prefer juvenile fiction, because a lot of the young-adult fiction features people doing stuff that they wouldn’t normally do unless they were married, but they’re not married. That makes me a little uncomfortable.”

Ramadan is still another crucial aspect of living halal. During this sacred ninth month of the Islamic calendar, Muslims fast, waking up before sunrise for a meal and praying afterward. While fasting, Muslims do not eat or drink, including water. Prayers are segmented throughout the day: dawn (“Fajr”), early afternoon (“Dhuhr”), later afternoon (“Asr”), sunset (“Maghrib”) and evening (“Isha”).

These daily prayers allow Mirza time for introspection. While he tries to pray five times a day, most days outside of Ramadan, he prays once in the early morning and once before bed.

“Living halal affects me in a positive manner because every (day) through prayer, I get to reflect upon my own feelings and show gratitude towards my own life,” he said. While many of Siddeek’s experiences with Islam have been shaped by her parents, she has gradually learned to embrace and interpret the religion in her own way.

“As I learn about (Islam), I’ve started to (follow) it more of my own accord because I understand it,” she said. “Just learning by myself and learning from my parents’ guidance has helped me to live this way.”

Sophomore Yoni Dadon and his friends often go to McDonalds to get a bite to eat. Each time, they order a feast of nuggets, chicken sandwiches, hamburgers and a myriad of other items on the menu. Whenever Dadon tags along, the menu of 145 items is narrowed down to his one — his only — kosher food option: fries.

In the realm of dietary customs, few are as distinct and meticulously specific as the kosher lifestyle. The English word “kosher” emerges from the Hebrew root “kashér,” symbolizing purity, propriety and suitability for consumption. This concept, deeply rooted in Jewish tradition, is governed by a set of laws known as “kashrut,” outlined in the Torah, the central reference of Jewish sacred texts. The application of these laws extends beyond simple dietary restrictions and encompasses a comprehensive lifestyle that influences not only what one can eat but also how food is prepared, processed and served.

Kashrut divides food into three categories: “fleishig” (meat), “milchig” (dairy) and “pareve” (neither meat nor dairy), each subject to strict guidelines. For instance, meat must come from certain animals that chew their cud and have split hooves, and these animals must be slaughtered in a specific manner to be considered kosher. Dairy products, on the other hand, must come from kosher animals and cannot be mixed with meat. Pareve foods, including fish (only with fins and scales), eggs and plant-based items, serve as a neutral category, compatible with either meat or dairy.

These laws not only dictate the types of foods that are permitted, but also mandate the separation of meat and dairy products to an extent that even the utensils and kitchenware used for their preparation must not make contact. The period between consuming meat and dairy varies among communities, typically ranging from one to six hours, reflecting the diversity in observance levels.

While some Jewish families follow these laws strictly, others do not. Junior Ronnie Horowitz, who grew up in a secular Jewish family in Israel, doesn’t restrict what she eats based on kosher guidelines. This approach to Judaism means that cultural identity may not necessarily include strict adherence to dietary laws.

“It never made me feel more or less Jewish,” she said. “I practice in my own way and those practices don’t include keeping kosher.”

In contrast, sophomore Yoni Dadon and his family have always maintained a certain degree of kashrut. His family follows the traditional waiting period between consuming meat and dairy, separates utensils and plates for dairy and meat, and factors kosher laws into restaurant choices.

“It means a lot to me because when I eat kosher, I feel more connected to my Jewish identity,” he said. “I’m upholding Jewish tradition and doing what my family did before me.”

Navigating the practice of keeping kosher often intersects with social dynamics, leading to moments of hesitation and stigma. According to Dadon, keeping kosher can occasionally impact interactions with friends, particularly when going out to eat.

“Sometimes, it can be embarrassing when I have to eat something kosher or order something special in front of others, but I try not to let it affect me,” he said.

Keeping kosher proves a challenge outside of home, because there are limited kosher restaurants and options in Palo Alto. Dadon’s family often eats at pizza places such as Domino’s when going out, or at restaurants like True Foods, which has a plethora of vegan and vegetarian options. Horowitz also noted that some students hesitate to share their dietary choices, and choose to instead say they are allergic or vegan.

“Keeping kosher is something friends are embarrassed to admit,” she said. “For example, my friend wouldn’t say he won’t eat pork because it isn’t kosher — he simply says he doesn’t eat pork. It seems too complex to explain.”

Exploring the varied paths of keeping kosher reveals a profound sense of identity and tradition for many, including Dadon.

“As I get more freedom as I grow older, I think I will keep kosher because it means something to me,” he said. “It’s more than just a diet.”

Horowitz’s perspective values personal choice and the diversity of Jewish practice.

“I don’t intend to change my lifestyle to fit someone else’s definition of what being Jewish is,” she said. “You should never tell someone how to practice their Judaism.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Henry M. Gunn High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.