This year, Louisiana joined the 45 states that certify girls wrestling at the high school level. Of these states, Kentucky, Rhode Island and Pennsylvania hosted their first state-sanctioned girls wrestling tournaments.

In the broader scope of women’s wrestling, the National Collegiate Athletic Association announced plans to add the sport as the 91st NCAA championship sport in winter 2026, with the vote set for next January. These recent developments mark the progress of girls wrestling as the fastest-growing high school sport in the country, according to the National Federation of State High School Associations.

Despite the uptick, wrestling remains a coeducational sport at Gunn due to a matter of numbers, according to head coach Jorge Barajas.

“Financially, we would have to figure out the number to grant another coach for a girls team and recruit more female wrestlers,” he said. “But (a girls wrestling team is) definitely the goal.”

Aspects of the coed practices, in which both genders drill against each other and compete with their respective gender brackets, have been ideal for junior Angelina Jiang.

“For me, (the routine is) mostly drill with the guys during practice and then go out and compete with girls,” she said. “It’s honestly a lot easier to compete with girls after drilling with these heavier, stronger guys. It just toughens you up.”

Wrestler sophomore Aurora Woodley embraces the opportunity to grapple with her teammates’ different styles.

“Being coed is being able to wrestle with a bunch of different people, which is more important than just wrestling with people who are stronger than you,” she said.

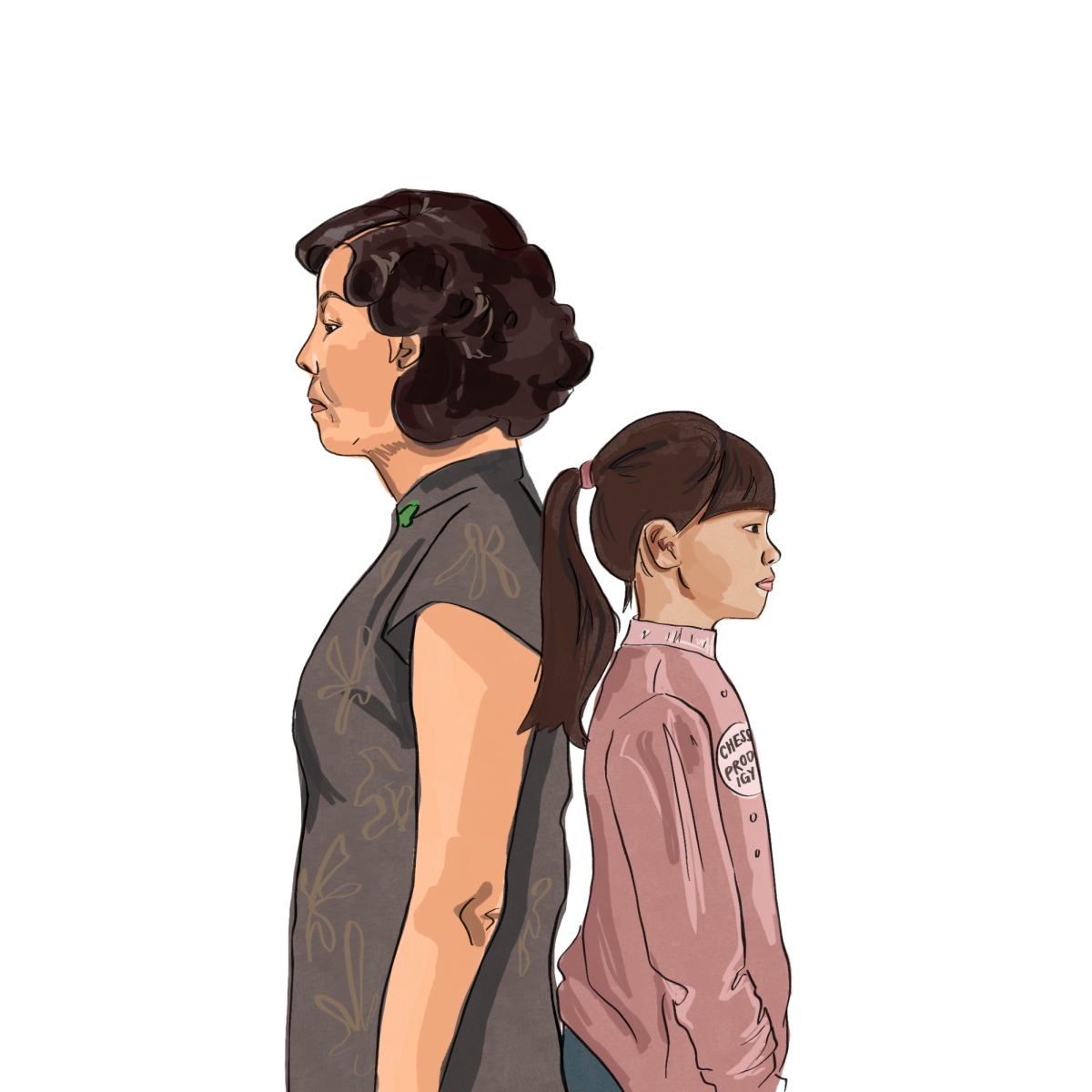

This season, the number of female wrestlers on the team has doubled. Alongside the returning members — senior Isabella Lee, Jiang and Woodley — the team welcomed five freshman girls: Mei Elgierari, Thea Kissiov, Avni Lochan, Zara Vivekanand and Mina Van Roy.

While these girls are the minority in the male- dominated team, this imbalance is the very thing that creates camaraderie, according to Elgierari.

“During the SCVAL (Santa Clara Valley Athletic League) sectionals tournament, (the girls) each went to one another’s matches when we could, and although some of us didn’t qualify, we still stayed together and supported one another,” she said. “It really helped, especially for those who weren’t done and were really nervous.”

Emerging players may shy away from the sport because they don’t know what the wrestling experience is like for girls.

“Wrestling is super intense, but people don’t understand that it’s not something that you should fear while being a female because the team is supportive of you,” Woodley said.

At the collegiate level, women’s wrestling is still something of a niche sport, as only four NCAA Division I institutions have varsity women’s wrestling teams: South Carolina’s Presbyterian College, Connecticut’s Sacred Heart University, and Missouri’s University of Iowa and Lindenwood University.

“Right now, there are only four colleges that have DI women’s wrestling, and a lot of colleges only have clubs or they don’t have women’s wrestling at all,” Jiang said. “So it’s really hard to get a scholarship. I know a lot of really good wrestlers, some who got into Stanford, (and) couldn’t wrestle anymore because there wasn’t a women’s wrestling team up until now.”

This limited opportunity does not deter Jiang from further pursuing the sport. Rather, fellow female wrestlers — such as 18-year-old Audrey Jimenez, who became the first girl to win an Arizona state high school wrestling title while competing against boys on Feb. 18 — have become role models for Jiang.

“There have been a couple of times where I’ve considered challenging one of the boys for a varsity spot for duels, because at duels, in all technicalities, a girl (is allowed to) challenge and wrestle guys, like in a lot of other states like Arizona,” Jiang said. “It’s not allowed the other way, just because of physiological differences. It brings up the whole thing of women in men’s sports and how women can bring themselves up to the challenge if they want to.”

Barajas recalls how 2014 Gunn alumna female world-level wrestler Cadence Lee, known for pinning down boys during her high school wrestling career, paved the way for girls in the absence of sanctioned girls’ wrestling. Because of women like Lee, along with women’s wrestling advocate Lori Ayres, who co- founded the organization D1 Women’s Wrestling and helped start the Stanford University women’s wrestling club, Barajas’ wrestling perspective has experienced a full-circle moment.

“I’m able to see where (wrestling) was to where it is now,” he said. “I think (local female forefront wrestlers) help our community of wrestlers. We have a good support system for girls’ wrestling just down the road at Stanford, where Lori Ayres is that voice (saying) that girls wrestling is something that needs to be going.”

For Barajas, coaching Jiang and Lee at the Feb. 22-24 California Interscholastic Federation State Wrestling Championships came against an important cultural backdrop: larger girls wrestling tournaments in the future. Girls state tournaments are now held at the same level as the boys’ and have full brackets. According to Barajas, brackets were around 20 girls, but now they reach 32-40 girls.

“If (this growth) continues, I could see the girls, within next year, at a 64-person bracket as well,” he said. “It’s just that fast-growing.”

Woodley has found that wrestling entails more than mere physical prowess, requiring intellectual and mental strength.

“I think it’s so important that wrestling teaches women how to deal with pain and loss and how to fight for yourself in the real world,” she said. “I’ve learned to just have the fearlessness to stand up for myself.”