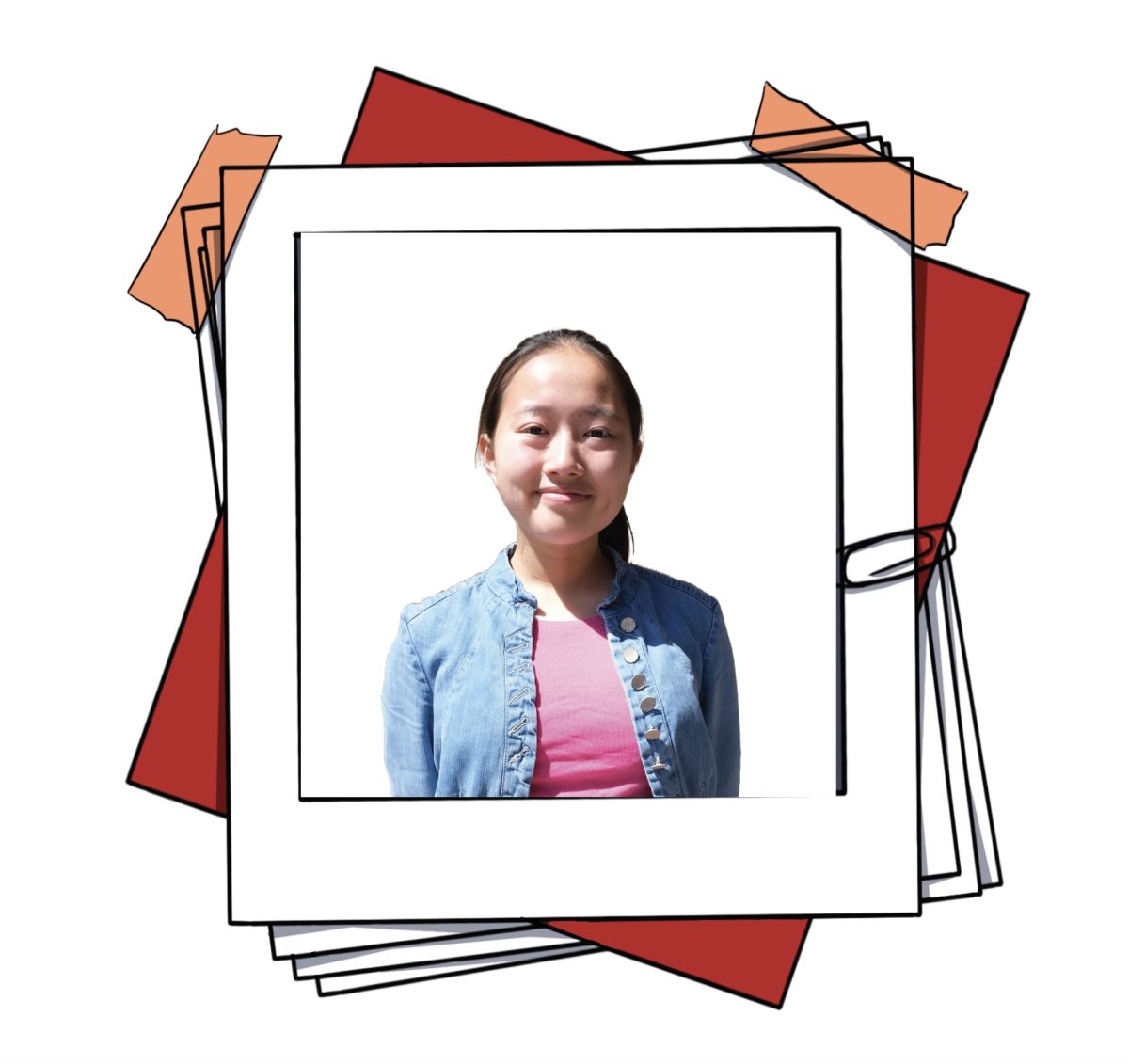

On her first day of seventh-grade summer school in Germany, freshman Alina Fleischmann introduced herself to her teachers and received the expected reactions from all but one: her health teacher. It wasn’t until she tapped her teacher’s shoulder that she found out that she was deaf. This interaction elevated Fleischmann’s interest in language through showing her the importance of communication.

Fleischmann’s journey with languages began early. Born into a multilingual family in California, her parents introduced her to German and Danish when she was a baby. Alongside these two languages, Fleischmann’s mom spoke Italian and her dad spoke French, further diversifying her language exposure.

“For me, language is a form of self-expression,” she said. “Knowing more languages makes our house a lot more expressive and a lot more vibrant.”

Although Fleischmann was born in the U.S., she moved to Germany when she was a few months old. There, she attended a British international school, where she learned English.

“I say words such as ‘hoover’ instead of ‘vacuum,’ or ‘queue’ instead of ‘line,’” she said. “Because I learned British English, it’s always a really funny conversation to have because (people ask), ‘You were born in California, German’s your first language and you learned British English?’”

By the age of 5, Fleischmann had moved back to the U.S. and begun attending Ohlone Elementary School, where she participated in the Mandarin immersion program for four years.

“It’s a thing in my household where everyone knows a special language that no one else in the household speaks, so (my parents) wanted me to have my special language as Mandarin,” she said.

Although Fleischmann became mostly fluent in Mandarin, she lost her proficiency after leaving Ohlone when she was 9 and started German Saturday school instead.

“If I don’t use (a language) regularly, I will simply forget it,” she said. “It’s harder for (me to forget) languages like Spanish, English and German because I am (completely) fluent in them, but definitely for upcoming languages, if I don’t practice or use it, I’m going to lose it — and it’s scary.”

Even when Fleischmann lived in Palo Alto, she occasionally visited Europe during the summers. She learned two more languages during these trips: French and Spanish. She began learning French at around 8 years old after an interaction she had at a party with a businessman her dad knew.

“He and my dad were talking about (me), so this guy said, ‘Introduce me to her,’” she said. “I walk up to him, he goes full-blown French on me and I (could not respond).”

After this exchange, Fleischmann’s parents urged her to learn French. Her lack of genuine interest in the language caused her to dislike it, however, and when she was required to choose either French or Spanish in fifth grade at her school in Germany, she opted for Spanish.

“I knew (French) and hated it,” she said. “My parents thought I should have done French. … In hindsight, that was probably the smart move because I’m now ‘bad fluent’ in both French and Spanish. I should have just stuck to one.”

That said, learning Spanish has allowed Fleischmann to better understand her mother when she speaks Italian, as the two languages share important linguistic similarities. For example, the word for a male cat is “gato” in Spanish and “gatto” in Italian.

When Fleischmann was 9 years old, she began classes to help her with her dyslexia. Fleischmann’s teacher taught her Latin word bases, which led her to fully learn the language.

“I am dyslexic, which makes learning this many languages even more freaky because learning languages is really hard for dyslexic people,” she said. “Learning Latin bases actually helps you a lot to decode (a) word. I was also really interested in Latin and kept learning it because I’m interested in medicine, and everything in medicine is Latin.”

In eighth grade, Fleischmann’s family moved back to Germany for a year. Hearing people speak a familiar language in a new setting allowed her to begin understanding and gain appreciation for the culture.

“(Living) in Palo Alto was quite the bubble,” she said. “It’s crazy. People don’t realize that there’s a world out there. I didn’t realize that either, and then I went and lived in Germany. I felt like I put glasses on for the first time because there was so much out there.”

Fleischmann quickly noticed that culture shapes language, and vice versa: Some words encapsulate ideas that simply don’t exist in other languages’ lexicons. These words are often adopted into other languages because they capture such a specific sentiment. For example, the word “schadenfreude” in German means finding pleasure in others’ misfortunes.

During her time in German school last year and the two summers prior, Fleischmann learned American Sign Language from her deaf teacher.

“For the first few weeks of school, I was completely fascinated,” she said. “Every time she said something, I asked, ‘What’s that in ASL?’ Eventually, she got so annoyed with me constantly asking her what things meant that she just offered to teach me after school.”

ASL opened Fleischmann’s eyes to both the possibilities and limitations of language. Before, she had not recognized the significance of the languages she knew because they were such a quotidian element of her life.

“The main reason I learned (ASL) was to try to connect with someone who wouldn’t normally be able to connect,” she said. “Most of (my background) of languages was that I just grew up speaking them, but this one specifically had a reason and impact.”

Overall, however, Fleischmann has found that each language she has learned — verbal or not — has improved her ability to communicate.

“It’s so much more powerful for me to say ‘I’m feeling exuberant’ instead of ‘I’m happy,’” she said. “Through the ability to manipulate and understand language, you’re able to connect with people because it evokes this emotion that all forms of self-expression do.”