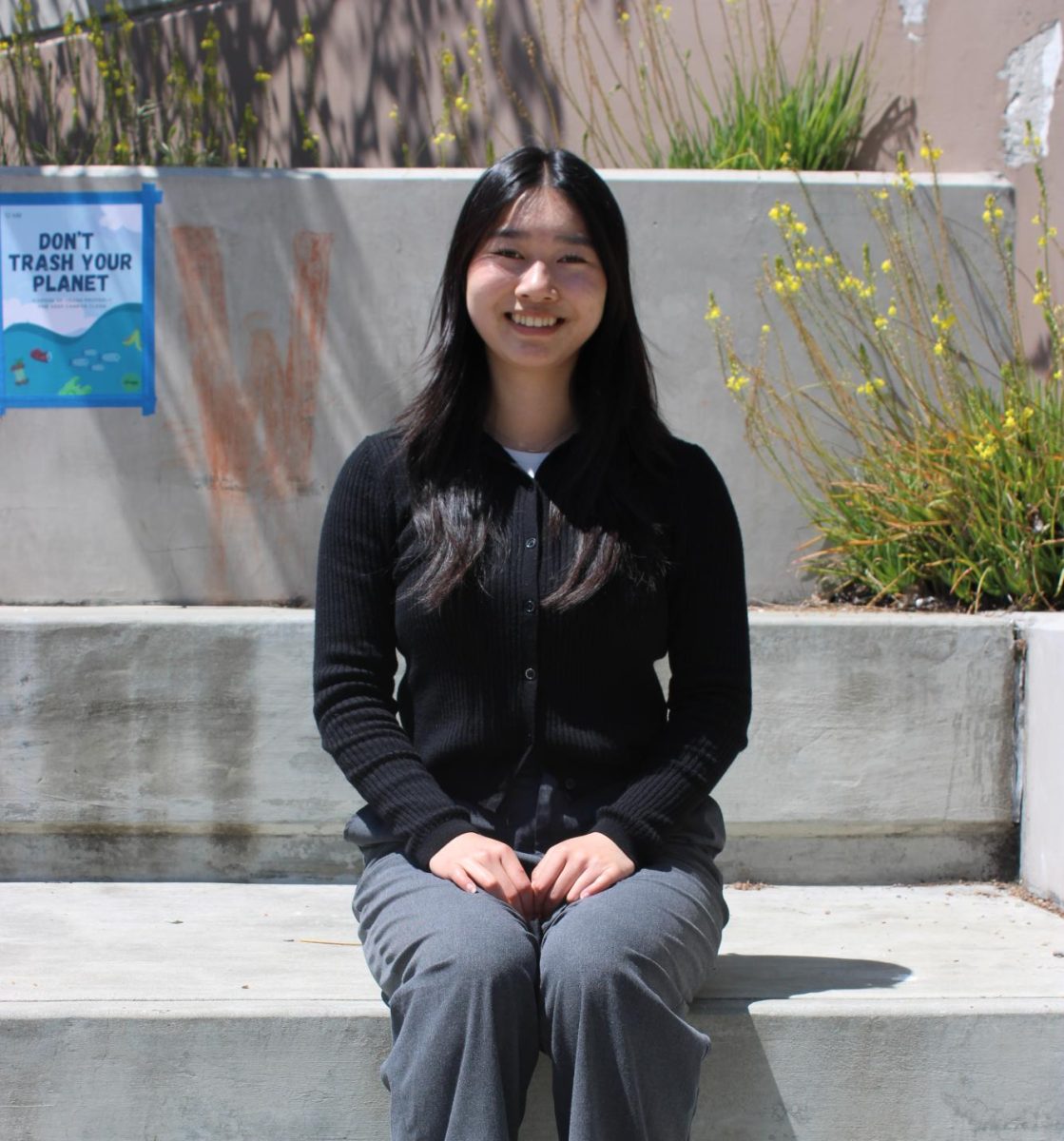

They say senior year is the best year for confessions (after all, who’s going to chase you down afterward? An ill-intentioned sibling? A teacher?), and in that spirit, here’s mine: I was — and, at least marginally, still am — a Stephen King fan.

All teenagers have their indulgences, and beginning in ninth grade, mine were “Misery,” “Pet Sematary” (no, it’s not misspelled), “The Shining” and all the rest. King’s books aren’t trashy by any means — far be it from me to insult the king of horror — but they were assuredly outside of my comfort zone. I’m by no means a thrill-seeker or a gore-lover, and I’ve often wondered what drove me to read about a psychotic clown in Maine, or a haunted hotel in the Colorado Rockies.

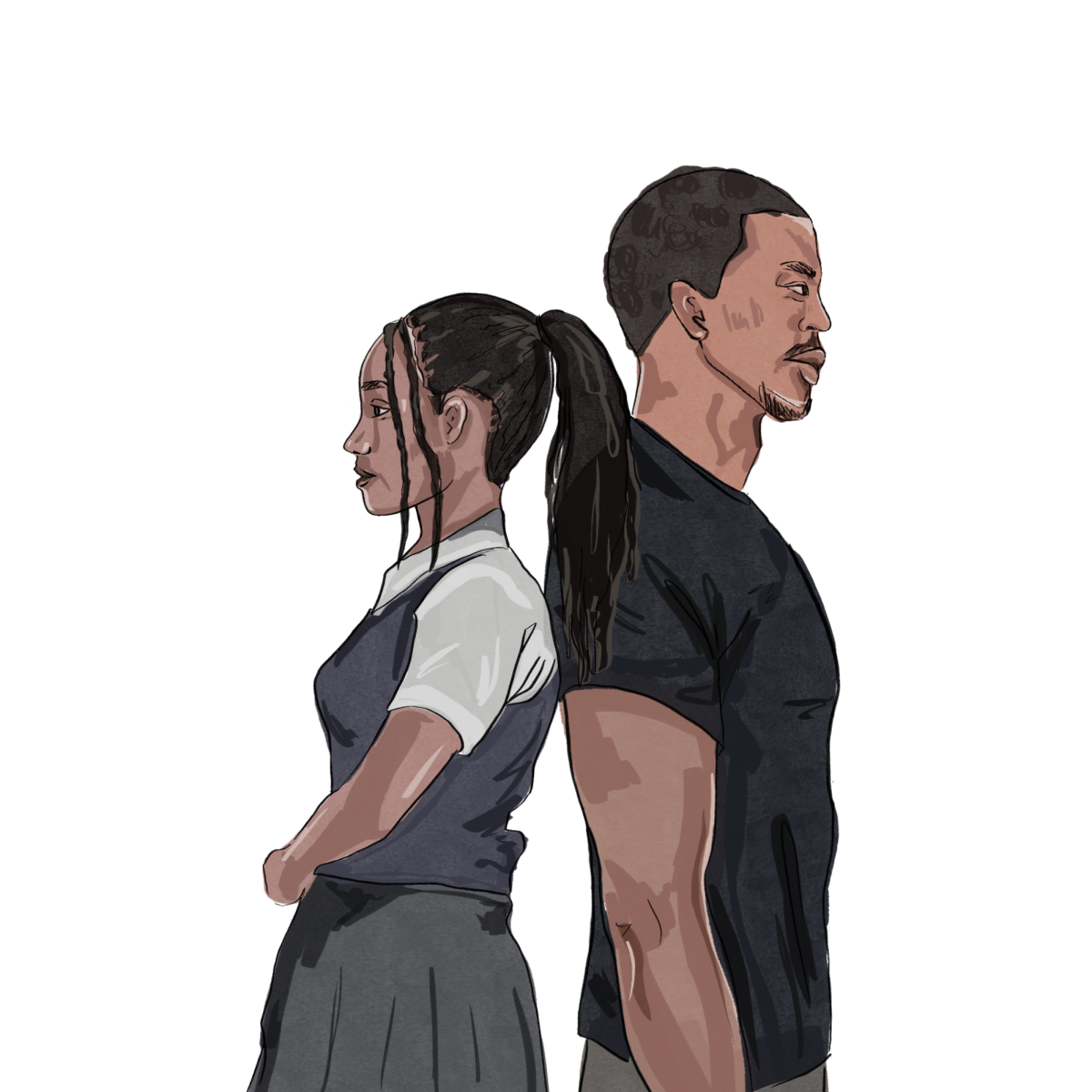

What I settled on was this: King’s books were perfect for me not because they were bloody, but because they provided a childish refuge. In ninth and 10th grade, I struggled to face the fact that I, and everyone around me, was evolving, perhaps beyond recognition. When I looked around me, I saw my friends eager to move on, grow up and be independent, and King’s books gave me space to cling to the familiar. His kid protagonists face unimaginable atrocities, but the solution is, in King’s words, to “remember the simplest thing of all — how it is to be children, secure in belief and thus afraid of the dark.” Defeating evil isn’t a matter of being the smartest or the most successful; rather, it’s an exercise in belief, maybe even in the suspension of disbelief.

So I took comfort in belief. Happy in my own sphere of comfort, I stuck with what I knew and avoided what I didn’t: driving, spending time with new people, trying new activities. I would go to school, go to basketball, come home, play piano, do homework, repeat. Monotonous, but predictable; static, but dependable.

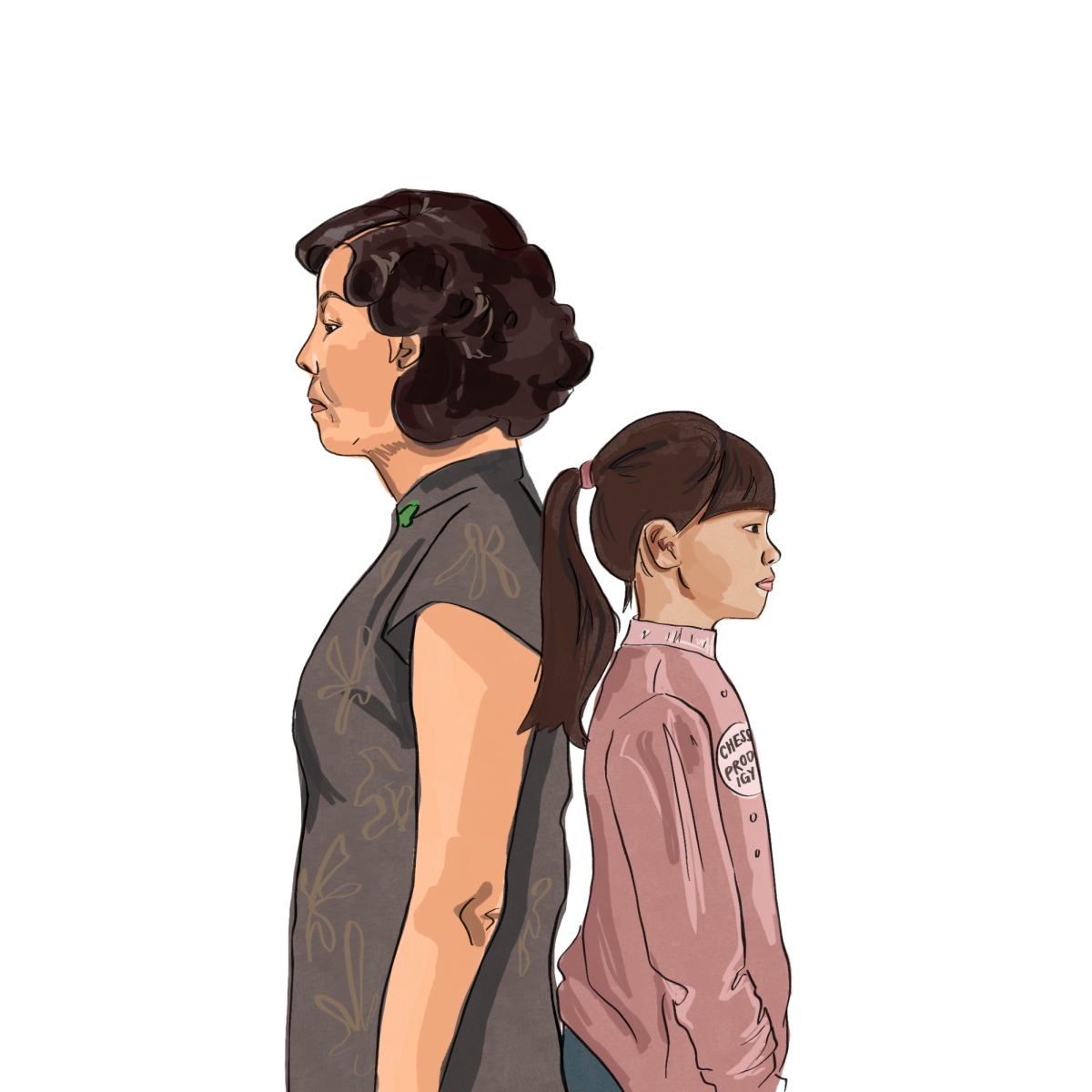

Beginning in junior year, though, I started to realize that shying away from change was not going to work. It was one thing to look at my elementary- and middle-school years with nostalgia, and another to stay mired in them, and I was tending toward the latter. And so I tried something new: I exchanged King for new authors, traded basketball for journalism and found new friends to add to the old. I felt a pit of anxiety in my stomach every time I pivoted, but each small step felt like a battle won against

my own fear of change.

It was only after I had begun to let go a little that I realized I had misunderstood King’s work. Being “secure in belief” didn’t mean taking refuge in it — it meant harnessing that childish awe, curiosity and empathy into adulthood. Growing up doesn’t entail abandoning childhood, but it also doesn’t mean regressing into it. My friends weren’t leaving behind their old exploits, but changing them into something new.

A few weeks ago, I picked up “It” from my bookshelf and — ignoring the clown’s garish smile on the front cover — thumbed through it again. The 1,100-page tome is, in the end, an ode to childhood, but it’s also a story of how we heal from and remake our childhoods as adults. After all, we are all still growing into our own stories, expanding and unfurling. Who knows what comes next?