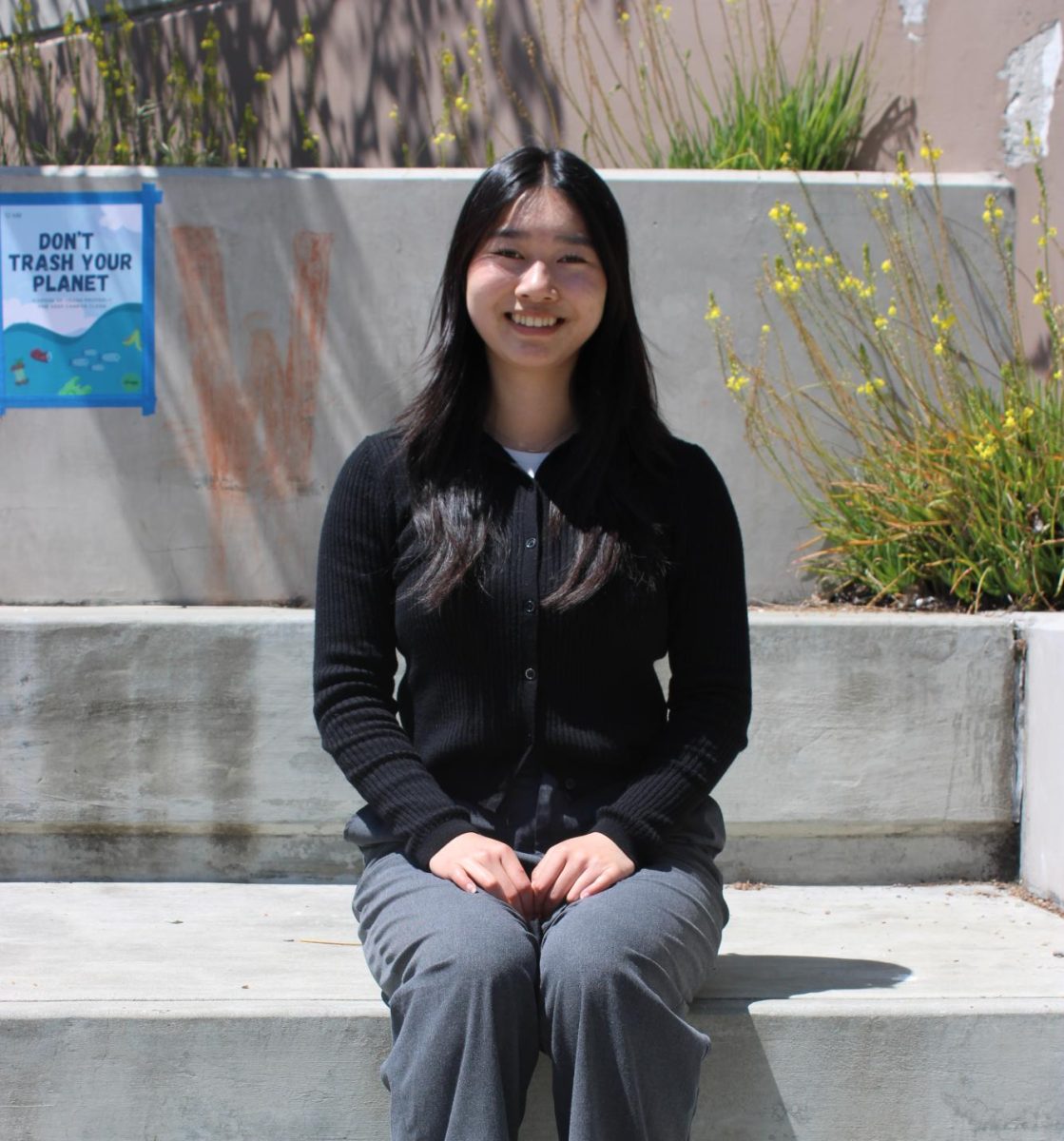

First to go were things: the cheap charm bracelet I’d bought in Okinawa seven years ago, the Kinder-egg toy, the expired library card from when I lived in Fullerton, the books I read once and vowed never to again. Paging through J.D. Salinger’s “Catcher in the Rye,” I felt the same frustration and unmet expectations that led me to hate the book in the first place. I set the book in the “donate” pile, ready to rid it from my life.

My first foray into minimalism — keeping only what holds value for me — in eighth grade focused on material things. I tackled my clutter because I wanted to rid myself of the weight of items that bore the burden of a past I no longer identified with. It seemed to be an avenue for growth, an invitation to newness.

I won’t lie and say it was easy. I value economy, and it felt supremely wasteful to throw away all

these things that were still “good to use.” These items, moreover, were rife with my personal history. I thought I could not bear to part with them.

So I negotiated with the selves I had been: the Irene who felt guilty playing with toys because she thought she needed to grow up, the Irene who could not stand Holden’s teen angst, the Irene who was not ready to leave her life in SoCal. In resolving tensions between my past and future selves, I learned about who I was and who I wanted to be. I redefined play as a necessary complement

to work; I empathized more with Holden’s directionlessness. I came to terms with my past by removing things from my life only after conscious evaluation; thus I shaped my present and took control of my future.

Much of my present has been formed this way, as I’ve extended minimalism to all areas of my life. One of the hardest decisions I made in high school was quitting competition karate sophomore year, which I’d invested hours a day into years prior. I loved the friends I trained with, the excitement of learning a new “kata,” the work that went into perfecting the basics. I felt that quitting karate would render the effort I’d put in meaningless. I feared losing the friends I had made, a slow moving apart that would return us to strangers. At the same time, I yearned to write and to grow in my writing-related pursuits in junior year. I chose this growth. And when I gave up karate, it was a subtraction that enriched my life.

So have other simplifications over the past year. I trimmed down my clothes to a capsule

wardrobe, a small collection of pieces that work together seamlessly. I withdrew from a nonfiction composition and reading Foothill class a few months ago to spend more time with friends and family (and to read fiction books instead). I turned off nearly all notifications. Each “no” is in a sense a “yes”: to more time with friends and family, to more mental bandwidth, to more energy on pursuits that matter to me.

Minimalism was how I found balance in high school, a way of asserting control when otherwise I felt in danger of drowning. It became a way to dissect my life, from the things I kept to the commitments I accepted to the way I spent my time. In the chaos of each day, I reached for simplicity. The sum is lightness and joy.