Officially introduced to PAUSD this year, teachers and administrators have been implementing Evidence-Based Grading to encourage students to focus on improving their skills over time.

Classes such as chemistry, AP Physics, and AP U.S. History are currently using EBG. This grading system uses a scale between one through four to assess students. Scoring a one represents developing proficiency, a two represents approaching proficiency, a three represents meeting proficiency, and a four represents exceeding proficiency.

Accounting for recency and consistency to determine a student’s grade, grades from recent assessments play a larger role in determining a student’s grade, while consistency shows that a student has a thorough understanding of the material.

Principal Dr. Wendy Stratton emphasized that the main disadvantage of percentage-based grading is that students are more focused on increasing their percentage than learning and understanding the course’s content.

EBG emphasizes not only teacher-to-teacher communication — which is essential to standardizing the grading process across classes — but also student-to-teacher communication, whether that be formal meetings or just asking questions after class.

According to Assistant Principal Kat Catalano, a main goal for EBG is to emphasize the importance of learning, as well as self-accountability.

“(EBG works to) build that sense of student agency,” she said. “The idea is that students know what they know, they know what they need to know, and they know where their gaps are. We want students to feel like they have a clear path forward, and I think that’s a really important practice for students who are going to go on to be lifelong learners — to recognize your gaps and figure out what you need to do to close them.”

Stratton finds that, instead of having students focus on ways to increase their percentage, EBG allows them to demonstrate proficiency in a skill.

“(EBG encourages students to have) targeted conversations with their teachers about what they need to do,” she said. “Not just (trying) to get 15 more points or 2.5 percentage points more — (Having students recognize), ‘I’m “approaching” in this area, can I provide (the teacher) with evidence that I am proficient?’”

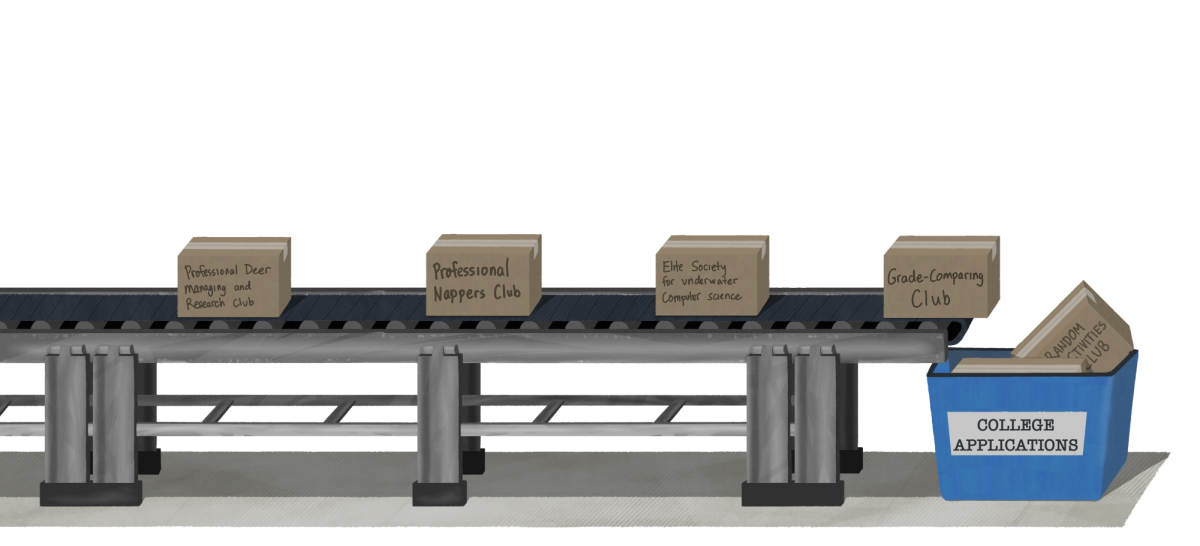

EBG has received varying levels of support from parents and students, as evidenced by an anonymous survey sent out by a group of parents to gather students’ opinions. Stratton and other teachers have made a continuous effort to meet with concerned students to address the pushback.

Sophomore Leza Hervy believes that EBG inaccurately represents her knowledge of the material. For example, Hervy’s chemistry class uses EBG, and she has noticed that if she does worse on the more recent test, her grade drops drastically, no matter how well she did on the previous test.

“One of the things I don’t like about (evidence-based grading) is that it is arbitrary,” she said. “The idea of EBG is that you improve over time, but most of the time, if you don’t understand the latest material, you might get a bad grade. Even if, percentage-wise, you should’ve gotten a higher grade (when averaging out the test scores).”

Hervy also feels that EBG does not accurately demonstrate a student’s overall grade. In some classes, students are provided with a grade sheet indicating if they met or did not meet the standards, but it does not provide a definitive final letter grade.

EBG can cause larger fluctuations in students’ grades, and this inconsistency frustrates Hervy.“In (EBG), if you get one question wrong, (your score might not meet the standards), and it will heavily impact your grade,” she said.

Despite some students’ negative opinions of EBG, teachers have found it to be a helpful grading system.

Science Department Instructional Lead Laurie Pennington uses EBG in all her classes and has noticed that it motivates students to understand the material rather than memorize it.

“(EBG) allows opportunities for learners of all levels to show, by the end of the term, that they know what they know, as opposed to having trouble in the beginning and then having to dig themselves out,” she said.

One thing she disliked with the standard percentage-based system is the difficulty to recover from lower grades — even if a student is capable of getting a higher grade.

“The other issue (with percentage-based grading) is for students who start off on a slower pace or get into a class that’s a little more difficult than they’ve taken before,” she said. “They get a slow start, even though they’re capable of learning at that level.”

Pennington appreciates the way evidence-based grading allows for students to fully comprehend the material and show what they know. EBG has allowed Pennington to make sure students understand the concepts rather than knowing how to use a formula.

“Is it more important that (students) know (force equals mass multiplied by acceleration), or is it more important that (students) know that, ‘If I push on something, it’s going to move’?” she said.

Students, teachers, and administrators have varied opinions on EBG, but ultimately, administrators look forward to integrating EBG into the majority of classes.

Catalano noted that a possible way to increase the accuracy of grades would be having more data points. Instead of taking fewer bigger assessments, teachers would create more frequent and smaller assessments — highlighting EBG’s goal of improving over time.

“The focus is on the learning,” Stratton said. “They’ll have a chance to talk about that with their teacher and figure out the misconception. (Students will) walk away from a course and from high school having a clear sense of how to push through something that’s challenging.”