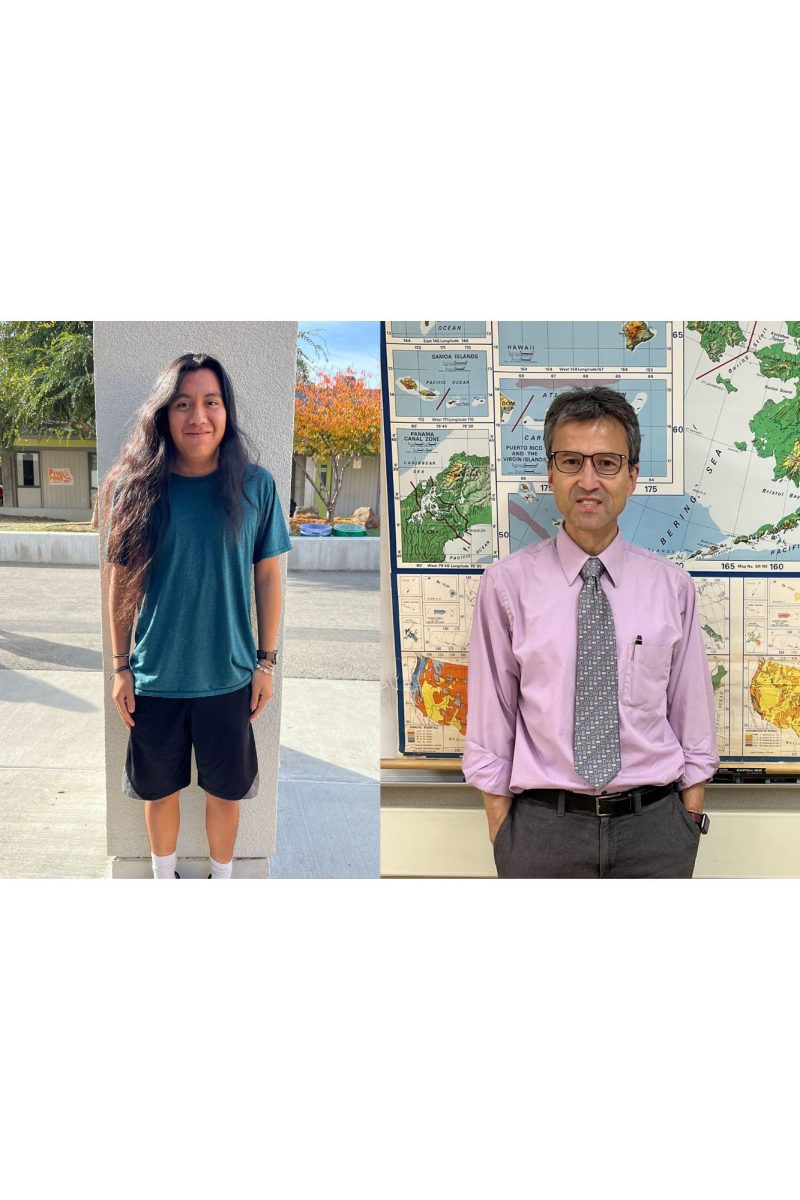

Written by Shawna Chen and Hayley Krolik

It was 1971 in California. Independent Studies teacher Ken Plough and his friends sat around the television watching the ping pong ball lottery system for the Vietnam draft. A ping pong ball was randomly fetched out of the deep glass jar, to determine the order of induction into duty, and the birthdate was read.

The men born on Plough’s birthdate had been chosen for the first wave of the draft. Now, Plough was to report for active duty.

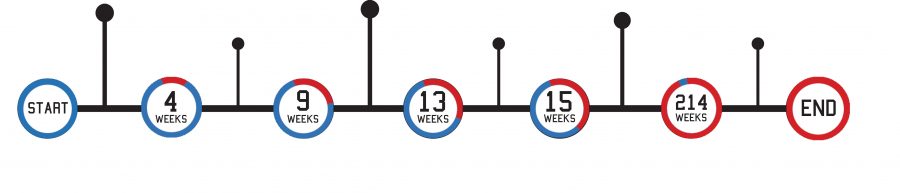

The next day, he enrolled in the Reserve Officer’s Training Corps (ROTC). The Naval ROTC, a college-based program designed to prepare soldiers for officer commission, would provide Plough with a four-year education and release him from active duty for the four years he would spend in ROTC under the Marines division. “Once I knew my number was first, I knew I had to report; I would get one semester in college and go to boot camp in Vietnam,” he said. “[But] ROTC guaranteed me four years in college, and when I did go into service, I would go in as officer instead of as an enlisted man, which is about three times the pay.”

However, plans changed when senior year arrived. One night, Plough returned to his unit and had a disagreement with his colonel. The seniors were all responsible for a group of freshman trainees, and Plough was assisting his trainees through inorganic chemistry. It was 3 a.m. when his colonel issued a battalion order, which called everybody out of bed and into an assembly, but Plough refused to wake his trainees, who had gone to bed late and were taking an inorganic chemistry test at 8 a.m. “[My colonel] said that if I couldn’t see the relevance of his order, then he couldn’t see the relevance in giving me a commission,” he said.

Though Plough’s colonel could have brought him under military charges, insubordination or even mutiny, he ultimately allowed Plough to resign from receiving his officer commission, and Plough returned to the regular status of a soldier.

Plough completed his college education and was preparing for graduation on Thurs., June 30, 1976 when in the morning, his commanding officer notified him that he would be called to service that afternoon. “Because I hadn’t completed my officer commission, I was as eligible as any other for the draft,” Plough said. “I had to report to duty for transit to Diego Garcia, a U.S. Navy Base in the middle of the Indian Ocean, but I had been engaged for a year and was supposed to get married that Saturday.”

The only way to avoid immediately reporting was to enlist in the Marine Corps for four years instead of the two years of active duty. “I was able to join the Marine Corps on Thursday, get married on Saturday and reported for boot camp on Monday,” he said. Plough spent four months undergoing physical and psychological training to prepare for the Vietnam War. “To hone our skills [and] go on patrol without being noticed, [our commanders] used to hunt us with dogs and helicopters because in Vietnam the North Vietnamese would [hunt] us with tigers,” Plough said. “We trained and we trained and if they thought they saw us, they would throw tear gas on top of us either using a grenade launcher or fly over us with hand grenades of tear gas.”

Additionally, Plough was placed through different schools, such as the Escape and Evasion School, where soldiers sustain various interrogation techniques, one of which was waterboarding. “We considered that just standardized training,” Plough said. “Today we read about it in the newspaper how horrible that is, but it was just part of our training regime.” Though Plough had been training for deployment in the Vietnam War, his unit was recalled when the Communist Party Khmer Rouge took over the Cambodian government and blocked the U.S. military from landing in the area. “We trained for a war that was ending up not being a war,” Plough said.

Instead, Plough was sent to engage in cold-weather training in Alaska. “They taught us how to use ropes to climb, how to free climb on the rocks, how to set rope bridges for other people, how to survive on a glacier and how to walk across a glacier,” he said.

Plough was ultimately never deployed to active service despite the mental and physical preparation. “It was a disappointment; mentally, you are all ready to go, and you’ve endured for so long,” he said. “They get you to such a point and then it’s just ‘No,’ but I came home, my son was there and I started raising a family.”

Even with the challenges, Plough doesn’t believe that his time in service overly altered or hardened him. “My radioman and I, we’re just as crazy now as we were beforehand,” he said, jokingly. “We might have had to grown up faster, but I don’t think we changed.” At the same time, Plough acknowledges how different his experience was. “At 25, I was responsible for $50 million dollars of equipment and the lives of 82 divers,” Plough said. “Not many 25-year olds have that responsibility.”

Looking back on his time in service, Plough is grateful for the incredible ventures in which he participated. “We got to go to some of the nicest places in California; we’d be up Adobe Lake Tahoe and Yosemite hiking through the mountains,” he said. “We learned how to survive in the mountains and how to mountain climb, and when we went in the winter, we learned cold weather survival.” Plough also lists patience, perseverance and endurance as three traits he embraced and continues to appreciate today.

For those considering joining the military, Plough cautions and encourages students to ask themselves why they want to go into service. “It can sometimes break people, and they will never be the same [while] for others it’s like putting on a nice pair of Italian shoes,” he said. “Our joke was the Marine Corps never promised you a rose garden.”