Written by Shannon Yang

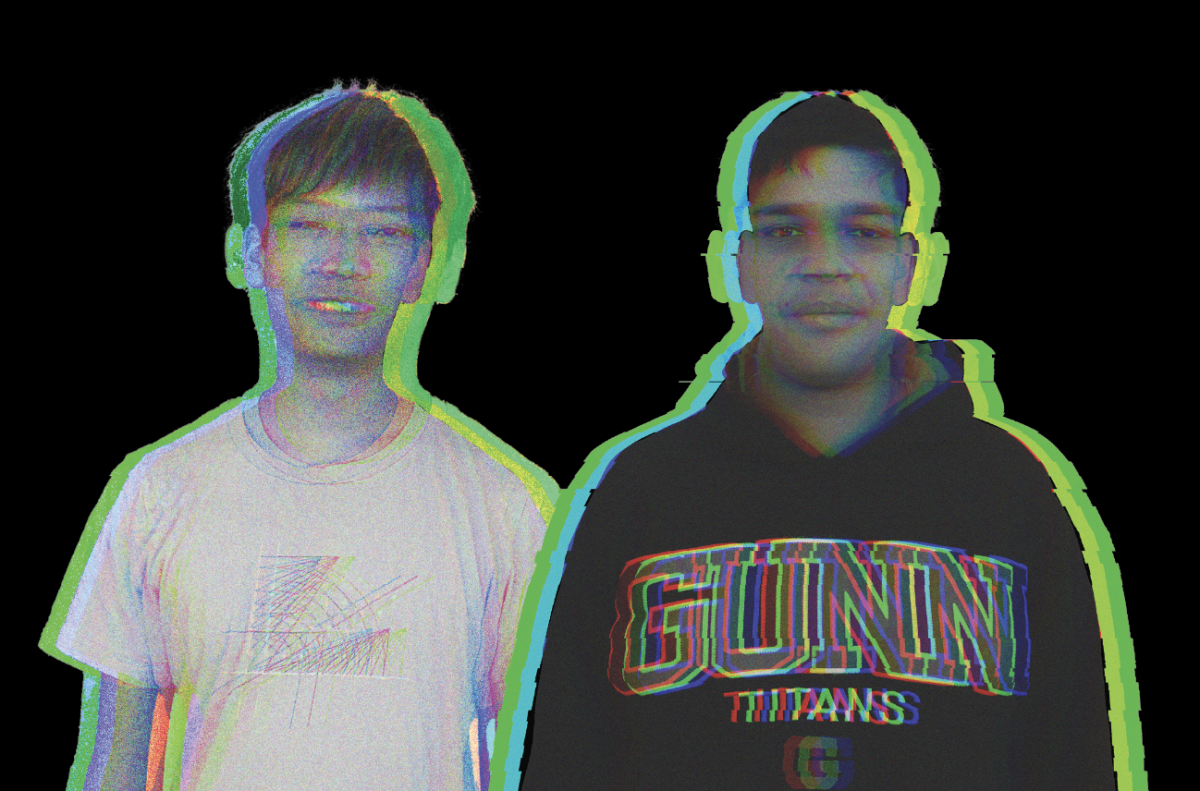

When sophomore Aldric Bianchi walked onto Gunn’s campus his freshman year, he noticed that not many people looked like him. Because he was born here in the United States, Bianchi considers himself an American by nationality, but Bianchi also considers himself a minority at Gunn. His mother is Brazilian and black and his father is French and white, yet Bianchi describes himself to strangers as “mostly Brazilian [and] black.”

According to Gunn’s 2015-2016 school profile, 2 percent of the school’s student population is African-American, while 3 percent is two or more races. “Freshman year, I found it a bit hard finding people who were black or Brazilian or French, and I was kind of solo in a way,” Bianchi said. “There aren’t many at Gunn who are black [or] mixed either. We have a small population compared to a lot of other races, like Indian [and] Asian.”

In comparison, Palo Alto High School (Paly)’s student body is 3.9 percent African-American, a higher diversity level that Bianchi believes would be beneficial for Gunn. “What I see here at Gunn is mostly major races: white American, Asian or Indian,” Bianchi said. “Paly is much more diverse.”

Bianchi says he often receives stares from others who question his race. “Last year, people would make fun of me for looking Arabic or looking a different race that I’m not,” he said. “People would say I’m no race or I’m weird just because I’m mixed race.”

For senior Menna Mulat, one of the ways that prejudice manifested itself was in the classroom. “My teachers ask me if I need help a lot, which I don’t mind, but at the same time it’s like some teachers kind of single me and other black students out and say, ‘Are you doing good?’ or ‘You need help?’”

However, Bianchi says that although he’s been treated differently, the school setting has improved throughout the years. Teachers have begun to listen to him more attentively and he finds Gunn to be more of an inclusive place. “When I was younger, teachers would ignore me maybe or brush me off a bit more than other students, but here at Gunn I wouldn’t necessarily feel that way,” Bianchi said. “Most teachers are very inclusive, kind and caring towards all the students.”

However, Bianchi believes that there are two sides to the situation. According to Bianchi, Gunn sometimes treats all black students as students who require more help and assistance. Although the extra attention can be helpful and increase the chances of going to college—as has been the case with students from Black Student Union (BSU)—Bianchi believes there is a fine line between offering help and racism. “At the same time, I feel like those kind of things can only go to a certain extent before it becomes patronizing and racist in a way and kind of racially profiles students for certain traits or certain actions,” he said. “People act weird [when] wanting to help us because it seems that we need help [and] like we’re in a difficult position.”

Senior Marek Harris agrees with Bianchi and recognizes that there is a problem with the way that teachers address minority students. “I don’t think that the way [district is] approaching the situation is very good because they’re mostly focusing on the negatives,” he said. “They need to focus on a solution and making sure everyone is on board and the solution is the most accurate way to help everyone.”

Mulat also feels treated differently as a minority. Growing up in Atlanta, Mulat was used to a larger black population. “It’s hard to be a minority at Gunn because not everybody comes from the same route that I come from,” she said. “When I moved here and I went to Terman [Middle School], I was different. It was kind of hard to get used to that.”

Mulat and Bianchi agree that black students are often put into a box and expected to meet certain stereotypes. This expectation made Mulat’s transition more difficult because although she is a social person, non-black students would stereotype her. She says she often received comments such as: “If you’re black, you’re only good at sports.”; “If you’re black, you do bad at this test.”; “How do you have such good hair? You’re black.”; “How’d you do [well] on this test? But you’re black.”

Bianchi points out that black people are portrayed more negatively in the media, which affects how others see him. “There’s supposedly [so] many different kinds of white people, but when people look at us black people, they usually see someone who is very ghetto, doesn’t have [a] good education, does drugs or drinks alcohol and has a temper and is likely to get in fights with people,” Bianchi said.

Bianchi believes that although white students’ actions reflect on themselves as individuals, black students’ actions seem to reflect upon the whole race. “I think that people shouldn’t try to focus on this aspect,” he said. “They should focus on the person in front of them instead of putting this veil around them and turning them into someone they’re not.”

To deal with these issues, Mulat and Bianchi turn to BSU, a club at Gunn that is open to students of all races. Mulat describes it as a family. “We talk about how we can stop [stereotypes] and how we can have other people not think the same way,” Mulat said. “If you’re having a bad day or if you had someone talk bad about you or stereotype you, we talk about that and we try to solve it and kind of deal with it.”

In addition, Mulat ignores mean comments she receives from people. “I don’t let it get to me,” she said. “I usually just ignore it and move on with my day or let them know just because I’m black, [it] doesn’t mean I’m dumb or my hair is fake.”

Junior Sofia Murray, founder of the Latin American Culture Club, feels like her culture has been overlooked at Gunn. “A lot of people assume that all Latin Americans look Mexican, and when you think of someone who speaks Spanish, most people assume Mexican stereotypes,” she said.

Murray’s status as a “white-passing Latina” makes it easier for her to assimilate into Gunn culture. “People don’t assume that I’m Latin American because I look white,” she said. “I think there’s a lot of assumptions that aren’t made about me. I don’t think I get put under any of the stereotypes or anything like that because of the fact that I look white.”

Murray identifies 50-50 in between white and Mexican stereotypes, and her identity shifts based on whether she is at home or at school. “At home, I identify a lot more with my Latin side because I hang out with my grandma a lot,” she said. “She lives with us, so I speak a lot of Spanish at home. I think when I’m at school, I’m a lot whiter.”

Bianchi has not learned much about minorities from his experiences at Gunn. “I think it’s really left out in some places,” he said. “People are aware of recent things like Martin Luther King Jr. Day. I saw my friends talking about it, but I think only one of my teachers talked about it. You really could have gone deep into those kinds of things, but now it’s more of an emphasis on math and science and going to college.”

Looking forward, Bianchi hopes that Gunn can implement more programs to include minorities. “Maybe in the next few years, we could include programs to increase awareness of the minorities here and open our eyes to some of these things,” Bianchi said. “I think it’s important to be really aware and open-minded about not just the black community but other races as well.”