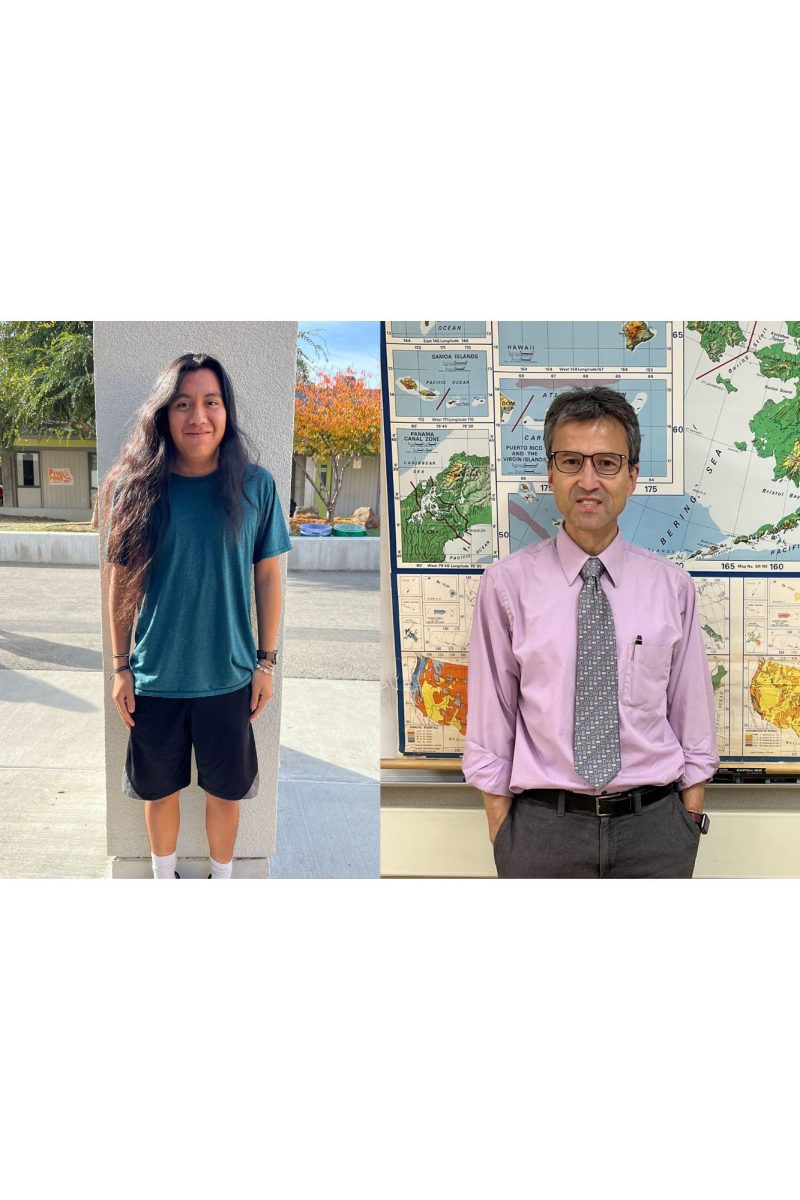

Written by Ryeri Lim

Upon first contact, the semantic formalities of South Korean speech often frustrate foreigners. Couples who are married for 40-plus years may still refer to each other by respectful titles. Someone may show marked subservience to a friend only six months older. Yet with some perspective, a method to the mannerisms emerges.

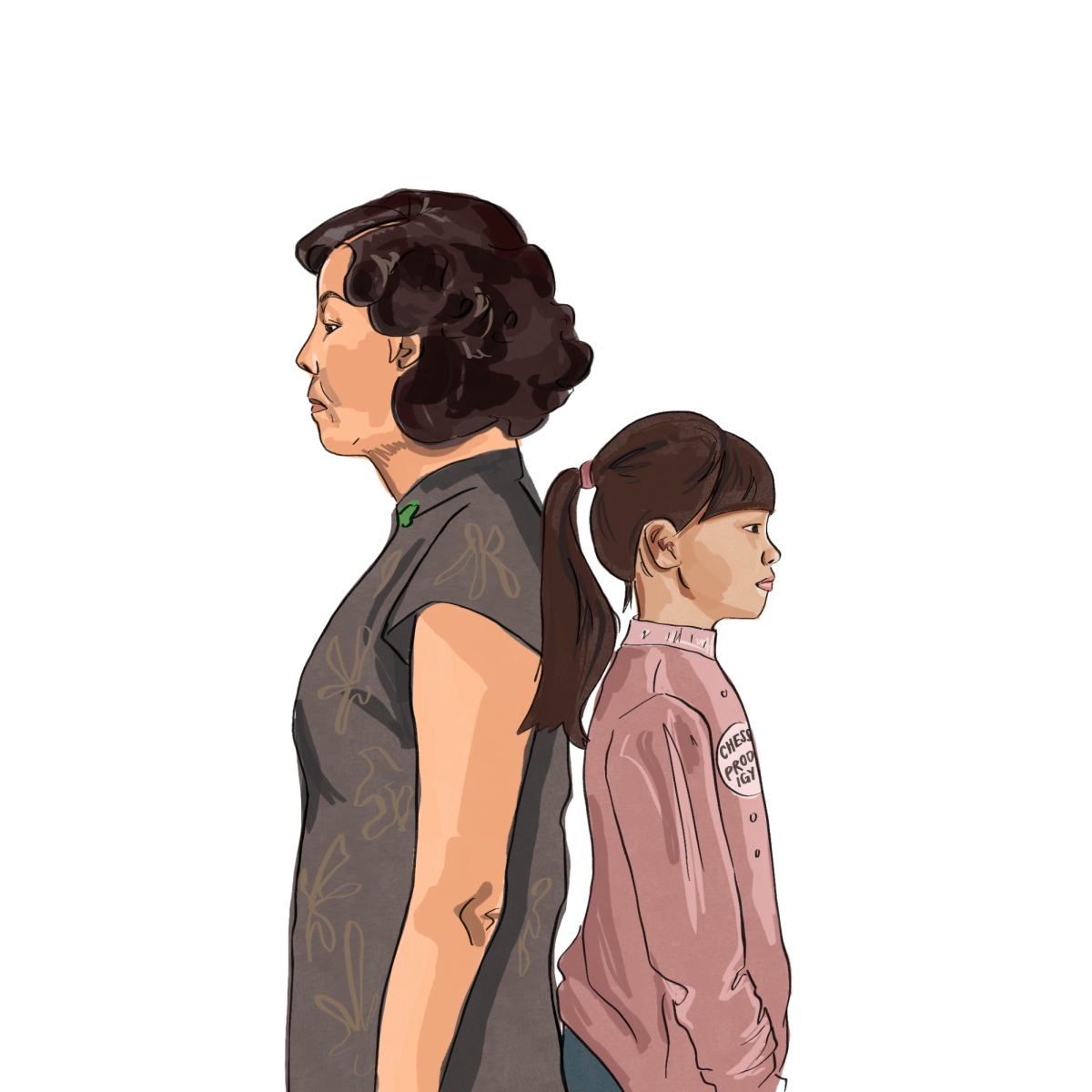

This is perhaps most understandable within the family structure. According to Hanna Lee, mother of senior Young Hye Lee, one of the most important things parents expect from their children is respect: an attitude that includes honesty and propriety. Many children, well into their own old age, speak to their parents with a restrained formality. “We always use honorific words, not only to adults [in the family] but also to older siblings in some cases,” junior Jueun Pyun said. This type of formality soon turns into a habit. The respect is returned with something particularly valued in Korean culture: all the scolding and nagging by parents holds unconditional support.

Support is also often prioritized in romantic relationships. Hanna expressed that she’d like her three children to date only a short time before pursuing marriage. “You can protect one another in marriage,” she said, verbalizing the high sense of duty and com- mitment taken on in Korean marriages, in exchange for essential partnership. Very few couples live together before marriage; closeness of that extent is typically interpreted as a signal to marry.

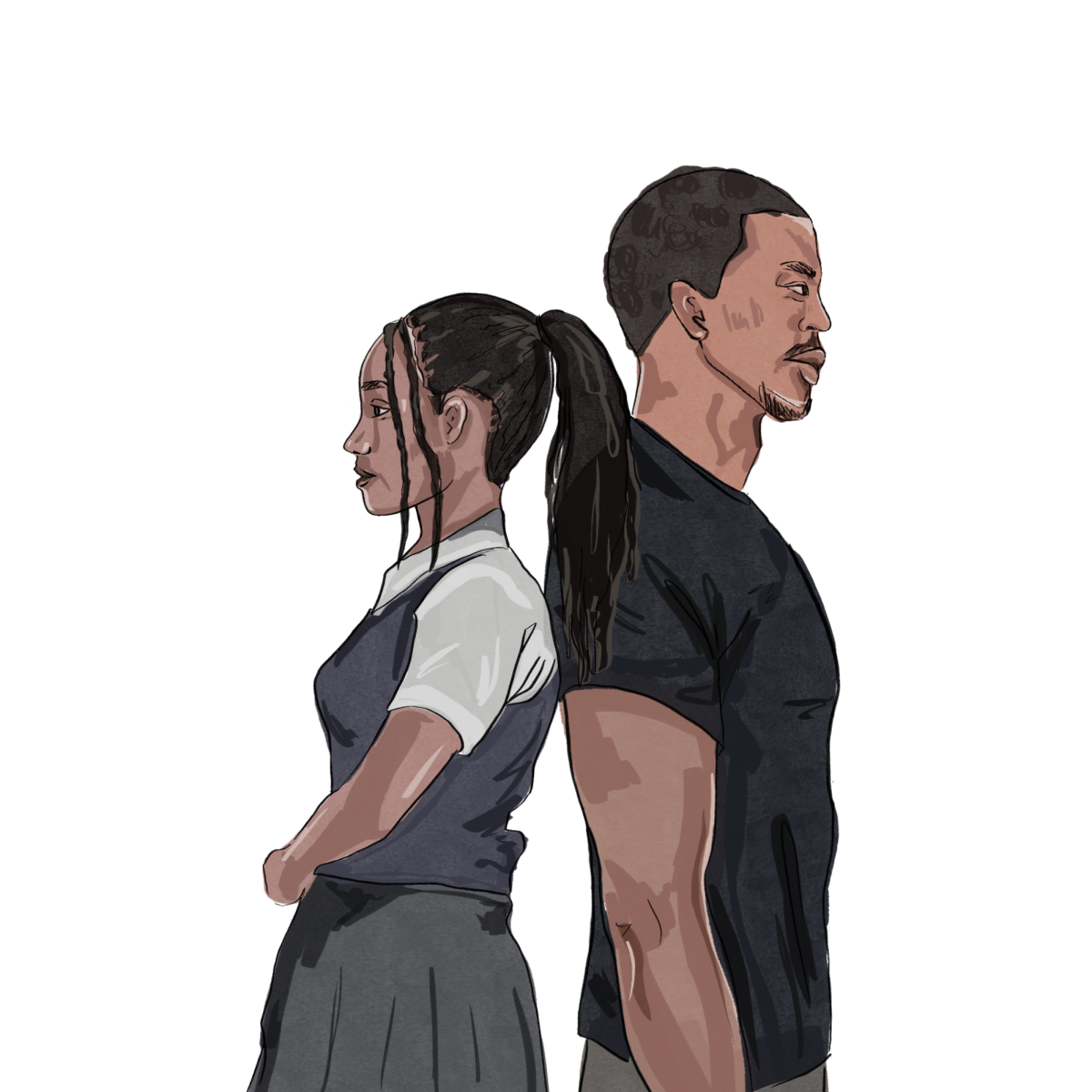

With this sentiment, social conservatism is natural in South Korea. For example, public displays of affection are a general faux pas. Couples instead claim each other through ranging levels of outfit “twinning.” Some simply coordinate patterns—polka dots or blue plaid—while some match exact androgynous articles from head to toe. According to a short feature by “Refinery 29,” couple-twinning is generally a way to share interests and grow closer. While individuals may feel conspicuous and cheesy at first, the matching “uniforms” convey that the two belong together. The underlying sentiment remains loyalty and dependability, two universal relationship goals.

Propriety is even prevalent in friendship; honorifics between friends or classmates of the smallest age difference are still significant. “When I moved to the United States, I was surprised that many American friends welcomed me,” Pyun said. “[In Korea,] there’s usually an awkward atmosphere on the first day of school.” Still, Pyun emphasizes that while the process may differ, the expectations are the same. “I think it’s similar to all countries,” she said. “Even though the Korean relationship seems difficult.”

These ritualistic aspects of interpersonal communication, rooted in generations of culture, are unlikely to dissolve anytime soon. For these formal words mark an informal contract: as such mannerisms create distance, they also guarantee societal respect for the institutions of family and friendship, and for the individual. Beneath the surface, they emphasize the values of trust and integrity in their world—a world which expands beyond national borders and even citizenship.