Written by Shawna Chen and Samuel Tse

On Jan. 21, the United States Departments of Justice and Education filed an amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) brief supporting the Chadam family in a DNA-privacy lawsuit against the Palo Alto Unified School District (PAUSD). The case, which was originally filed in 2013, dismissed in the district courts and appealed on Jan. 14, involved former Jordan Middle School student Colman Chadam, who was ordered to transfer schools after his medical information was divulged to another family without his parents’ consent.

The district removed Chadam from Jordan in 2012, when he was 11 years old, claiming that a doctor’s recommendation had caused district officials’ decision to transfer Chadam to Terman Middle School. According to the appeal however, that doctor has never examined Chadam or spoken with Chadam’s parents.

Chadam carries the genetic marker for cystic fibrosis (CF), an inherited disorder in which the lungs and digestive system become clogged with thick mucus starting in early childhood. But because he inherited only one marker and not both defective genes, which must be present for a person to actively carry the disease, he is not affected nor does he affect others.

The Chadams were asked to fill out a medical form upon registering at the district and included Chadam’s condition.

On Sept. 11, 2012, when a teacher mistakenly revealed to another Jordan family that Chadam has cystic fibrosis without permission from the Chadams, the family—named family X in the lawsuit—asked for Chadam to be moved to a different school so that their two children who do have CF would not cross infect.

People with CF are generally recommended to keep at least six feet away from others with CF, according to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. A person with the disease can be a carrier of bacteria that is easily transmitted and harmful to others with CF.

Chadam, however, “does not have, and never has had, cystic fibrosis and is a healthy teenager,” says the amicus brief filed by the Departments of Justice and Education.

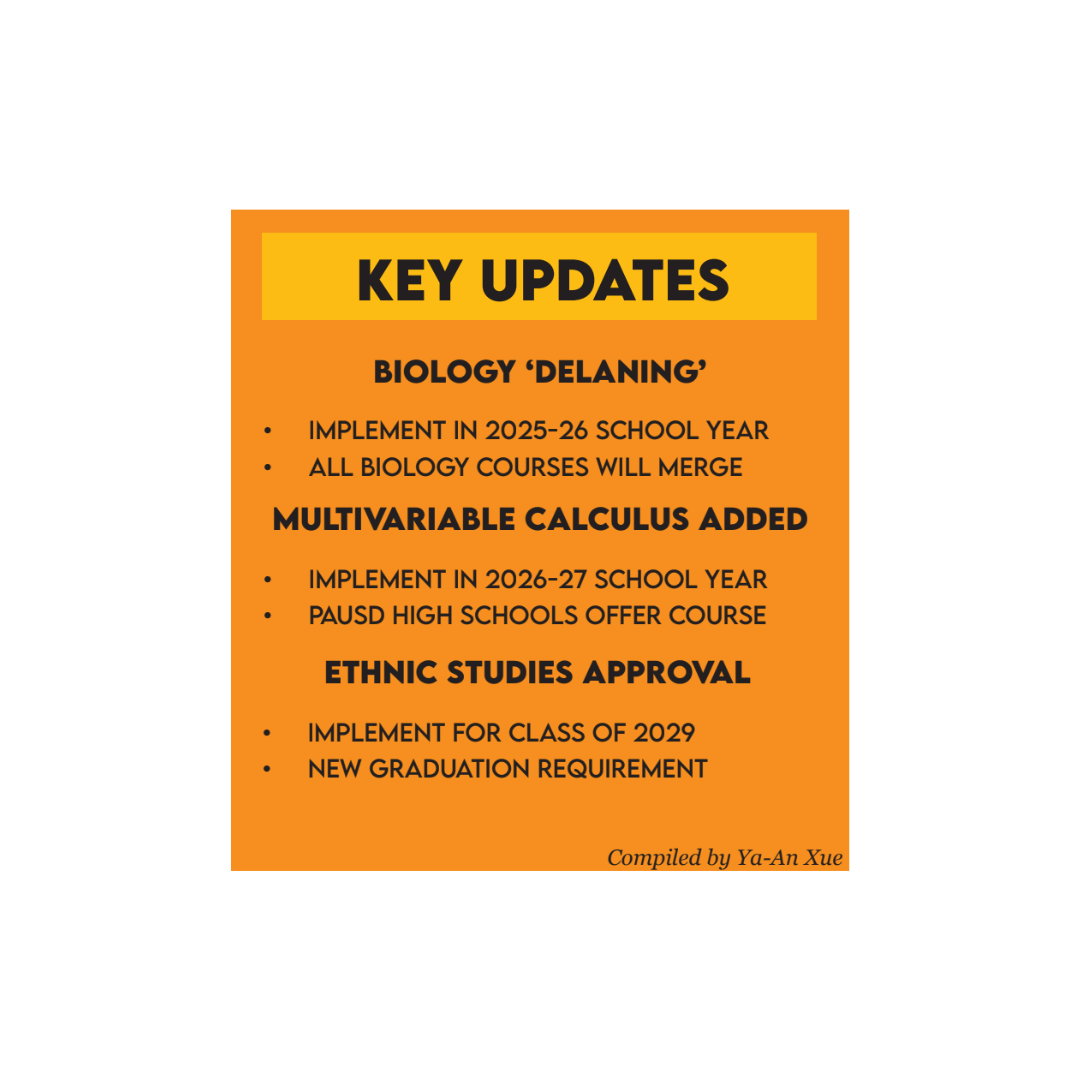

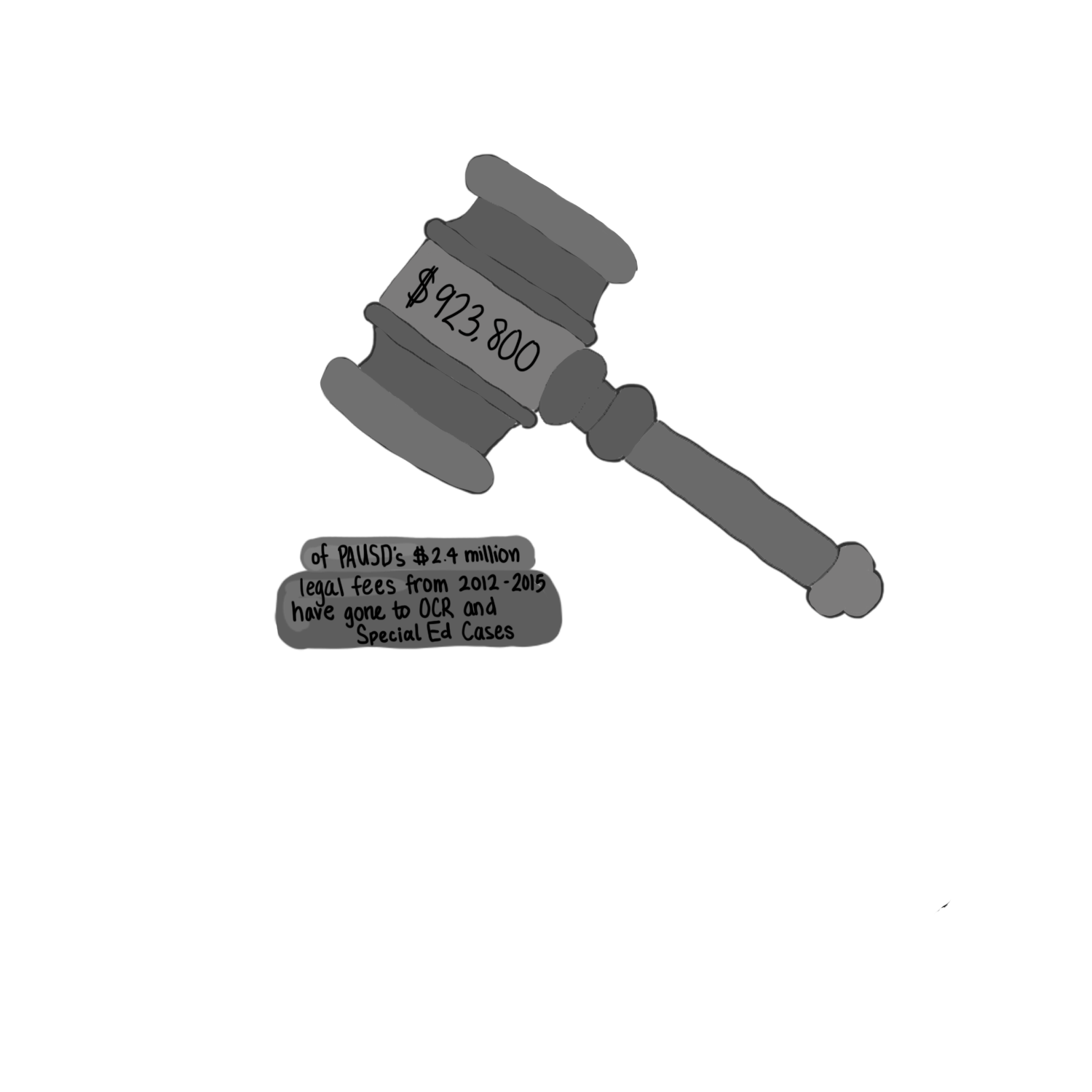

This is not the first discrimination lawsuit against the district. In the 2011-2012 year, PAUSD handled four Office of Civil Rights (OCR) cases, two of disability-based harassment, one a claim of race-based discrimination and the last alleging the district’s failure in following procedures in managing accommodations under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act.

The district disputed the OCR findings in 2013, with the Board of Education exceeding its legal budget by $110,000 and then-board Vice President Barbara Mitchell accusing the OCR of interviewing students without parental consent even though internal PAUSD documents contradicted her statements. Principal Dr. Denise Herrmann also stated that “the district does incur significant legal expenses throughout each year.”

The case

Though Chadam’s parents presented the district with a letter from one of Chadam’s doctors, who said that Chadam does not have CF and is not “any risk whatsoever to other children with [cystic fibrosis] even if they were using the same classroom,” the district only said its decision to transfer Chadam was according to a letter from an unspecified Stanford doctor.

“A few weeks later, [Chadam] was removed from class during the school day in front of his classmates and told that it was his last day at that school. Distraught, he walked home without saying goodbye to his classmates,” the Departments’ brief stated.

In October 2012, the Chadams filed a lawsuit in state court seeking to prevent the school district from transferring Chadam; weeks later, both parties reached an agreement and Chadam returned to Jordan.

A year later in September 2013, the Chadams filed a suit seeking damages, alleging that PAUSD violated the Americans’ with Disabilities Act (ADA) and that “as a result, [Chadam] suffered humiliation, anxiety, deterioration of his grades, and various physical ailments,” with other counts alleging violation of the “federal constitutional right to privacy” and common law negligence.

The district moved to dismiss the case in court, stating that Chadam’s transfer was not because of his disability but for the protection, health and safety of others.

The district court agreed with PAUSD, but the Chadams appealed the decision to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. After the Chadams filed their brief, Chadam lawyer Stephen Jaffe said in an email that the Departments of Justice and Education filed its amicus brief without Jaffe asking them to do so.

The Departments’ brief states their reasons for supporting the Chadams. Although Chadam does not have a disability, “[a]n individual meets the requirement of ‘being regarded as having such an impairment’ if the individual establishes that he or she has been subjected to an action prohibited under this chapter because of an actual or perceived physical or mental impairment whether or not the impairment limits or is perceived to limit a major life activity.”

Attorney Rodney Levin, representing PAUSD with a response, stated that “the inquiry is not whether a direct threat actually existed (i.e., cystic fibrosis vs. genetic marker), but rather whether district staff believed there was a significant health/safety risk.” He continued, writing that “[t]his case in part illustrates the heavy burden of student health/safety that school administrators bear” and district officials considered the risks at hand and “understood [them] to be substantial and real.”

The threat was not “one of a pet dander allergy,” the district brief reads, but of a “severe medical calamity—enough to prompt a doctor to state that the students ‘must not’ be within the same school environment.”

For the safety of all children, “district staff need to be able to make such critical decisions without the fear of reprisal and liability,” Levin wrote.

When contacted for interviews, district officials declined to comment and stood by its media statement: “The Palo Alto Unified School District cares about and is committed to the safety and well-being of its student population. That said, the case is on appeal because the Federal District Court found the claims insufficient to allege fault on the part of the District. PAUSD continues to agree with the ruling of the Federal District Court.”

Attorneys Jaffe and Levin both refused to directly comment for the story, citing ethical misconduct.

Herrmann, though not involved in the DNA privacy lawsuit, reiterated that the district tries to make the best decisions possible for all its students. In complex cases, not everything is clear cut black and white, Herrmann says; after all, the family, administrators and people involved are the only ones who know the whole picture. “There’s so much unknown that I wouldn’t want to speculate,” she said. “In other circumstances that I’ve been a part of, there’s information that I knew, as a principal, that I couldn’t tell other people because otherwise I would be violating my ethics as an administrator.”

Families, however, do have a right to privacy of information, Herrmann says. When requiring communication of medical information, the school requests a process where a family signs the right to exchange information between the school and doctor. “And most families do because they want us cooperating with the doctor: they want us to know what medicine the student is on, make sure that the right amount of medicine is taken and the doctor knows that there’s certain symptoms,” she said. “We take the doctor’s expertise and use that to then make the best educational decision we can.”

ADA & Section 504

The Americans with Disabilities Act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act ensures that students with disabilities have access to programs, services and activities within a school. An Individualized Education Program (IEP) is a legal document that describes the educational program that meets a student’s individual needs.

Assistant Principal of Student Services and Counseling Tara Keith emphasized that students’ privacy is of utmost importance. “All student records are on a need-to-know basis,” Keith said. “So only the people directly with the student have access to any information about that student, and there would be different levels of information that would be accessible to different people. For medical records we have something called a release and exchange from the district so we would send a release and exchange through the family of the student to the medical provider and they can decide if they want us to communicate with the provider, but that provider also provides us one. And then whoever’s name is on the release and exchange is who can have that information.”

Students who are supported by an IEP or a 504 are given accommodations that adjust for each student to fit their needs depending on the nature and severity of the disability. “One of the most important things when we look at a student with disabilities is looking at what they need to be successful and also what success means for that student,” Keith said.

Keith also says communication is important. “It’s making sure that we’re communicating effectively not just talking to talk and making sure it’s all about the students and so when we are talking about you that we’re talking about you, that we’re doing what you need,” she said.

After the multiple disabilities discrimination lawsuits against PAUSD in 2011, Keith states that the district has done a lot to move forward. “I think the biggest thing is moving towards being a more inclusive community and really look at the difference between things being equitable and things being fair, and really making sure students are getting what they need not just getting whatever everyone else has,” she said.

Student experience

Senior Melis Diken, a student with cerebral palsy, says officials higher up on the ladder don’t often take the time to really get to know students with disabilities and how to help them. As illustrated by the current DNA privacy case, Diken says the district will not do anything unless sued. But instead of fighting lawsuits in court, the district should better equip its staff and follow through when students and parents make requests, she says.

Diken, who said she often spent lunchtime in middle school sitting in the bathroom, says students with disabilities are often misunderstood. Administrators and district officials’ lack of communication, she says, can worsen the situation. “The teachers and staff often don’t have direct conversations with the students themselves,” she said.

Diken’s former aide, the school official she says knew her best, was not allowed at any of her IEP meetings, she says. “My guess is the district people don’t want to know the problems because they don’t want put the effort in to find a solution,” she said. “But it’s critical for them to ask.”

Diken understands that students are not always certain how to act around students with disabilities. Awareness can change that, she says. “Not only Gunn but the whole district really needs to inform the students around [students with disabilities] to say, ‘Hey, how are you doing?’” she said. “Invite them to hang out or even outside school. No matter whether you have a disability or not, every students wants to be included.”