Written by Deiana Hristov and Shagun Khare

Every day, junior Karla Henriquez wakes up at around 6 a.m. while most of her friends are still asleep. Her parents have to leave at 4 a.m. in the morning to start their work, so she is left by herself to get ready and eat breakfast. At 6:30 a.m., she then hops on a bus for a 40-minute ride to school—and that’s the easy ride. If she needs to take the bus back home after school, she has to ride three different buses for a total of one hour and 30 minutes before she can finally step into her home, catch her breath and start her homework.

Henriquez lives in East Palo Alto. When she was in kindergarten, there was a shooting in front of her local elementary school. Although she was the top student in her class, her parents were scared and did not want to risk her safety, so they decided to transfer her to the Palo Alto Unified School District (PAUSD), where they knew the education was top-class and where they knew she would be safe. “It’s honestly all about the money,” Henriquez said. “It’s way too hard to have a life here in Palo Alto when you are living on a budget.”

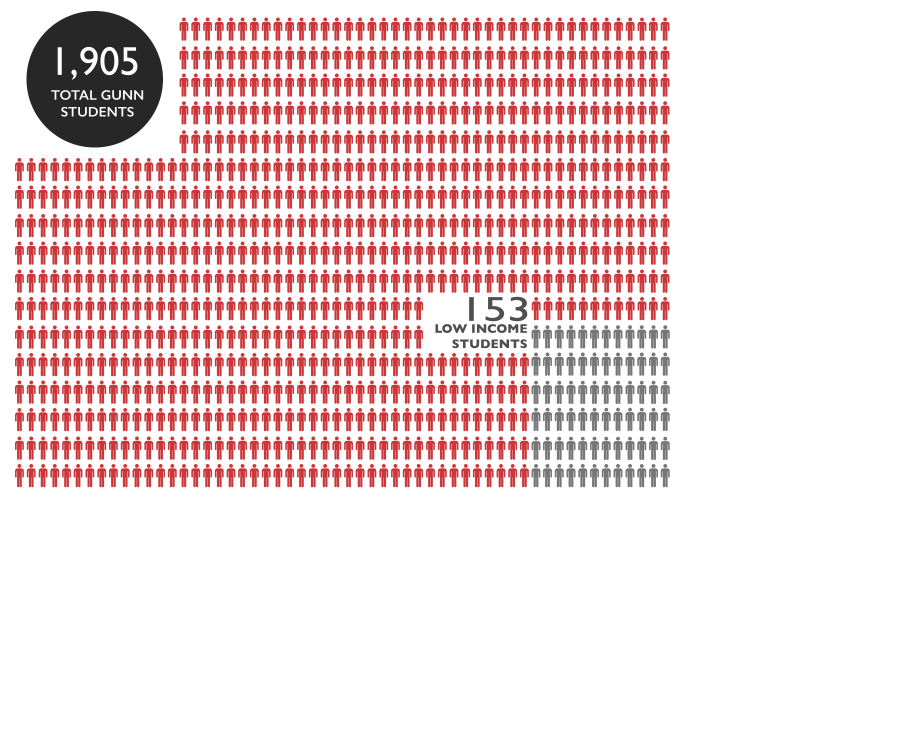

A long bus ride and lofty housing prices are only an ounce of the struggles that low-income families face in Palo Alto, according to PAUSD Director of Academic Supports Judy Argumedo. She says low-income students face obstacles in various aspects of their academic and social life throughout their high school experience and beyond.

The Obstacles

Junior Sally Fischer (name changed) and her family have had financial struggles for several years ever since her parents brought her brother to the United States from El Salvador. Although Fischer and her parents were grateful to finally have everyone together, it foretold the beginning of financial struggles for their family. “[It] kind of set the beginning of the debt that we started sinking down in,” Fischer said.

Fischer’s mother has a high school diploma, while her father attended college for two years in the United States before having to drop out due to financial reasons. Fischer’s father now works three jobs so that the family can get back on their feet financially—working in maintenance full-time as well as driving for Uber and Lyft part-time. According to Assistant Principal Heather Wheeler, the challenges that stem from being a low-income student start with the little details that the average Palo Altan—who makes one of the top incomes in the nation, according to CNN—might not notice. “[Some take] it for granted that somebody could pay to go out to lunch, or pay to get a tutor or pay to go on a school trip,” Wheeler said.

Henriquez has experienced these disparities first-hand. “My mom has tried to sign me up for free lunches five times, and I tried to sign up myself up and my brother up this year, and still we just can’t get in,” she said. “The district thinks that my parents are rich but I can barely afford bringing a lunch from home.”

Additionally, Henriquez faces barriers in the opportunity to further her education. “I was nominated for these [programs] made by the government and one of them was to go to Washington D.C and Oregon, but it is so expensive, so I obviously just could not say yes,” Henriquez said. “The money has stopped me from doing it.”

Argumedo believes high rigor at Gunn can further debilitate a low-income student’s ability to thrive academically. “Some students go out and get extra help from tutors, which gives them an advantage. A low-income student is not going to have that resource, and so it makes the gap much bigger,” Argumedo said.

Henriquez, whose parents do not speak English as their first language, feels jealous of students who are able to use their parents to obtain academic support. “My parents have a hard time reading my school material, so at times they don’t bother,” Henriquez said. “It upsets me, but I can’t be mad at them because I know they try, and if they could help me I know they would.”

The price of a college can limit a low-income student’s college options as well. Both Henriquez and Fischer must face the added stress of prioritizing price over appeal in their college decisions come senior year. “In picking a college for [low-income students], you have to look at the price,” Fischer said. “Whatever college offers the best price for you, you kind of have to choose it.”

However, out of all the challenges low-income students face, reaching out for help can often be the most difficult. “In a school where a lot of kids can afford a lot of expensive things, it can be hard to reach out because you’re shy that you can’t pay for something simple like the ACT or SAT test,” Fischer said. “You can be hesitant.”

To ameliorate the wide range of obstacles low-income students must overcome, Henriquez believes that it is vital for the district to become more cognizant and involved. “Yes, I get a free bus pass, but I can’t always take the bus home. We have to get school supplies. They [my parents] had to buy me a laptop because of all of the homework online,” Henriquez said. “I think they [the district] need to recognize that even if we have enough money so that they think we can support ourselves, we really don’t, because they don’t take into account all the actual things we need.”

Dedication to Education

Despite the numerous challenges low-income students face, Argumedo notes that low-income families demonstrate a dedication to education. By participating in the Voluntary Transfer Program (VTP)—a program made for East Palo Alto residents, 66 percent of whom are low-income—according to Argumedo, the bus ride provided through VTP from East Palo Alto to Palo Alto can take up to 40 minutes of students’ mornings. “That ride is long, but I think it shows the resilience and determination of the families still choosing to come to Palo Alto,” Argumedo said. “The commitment from the those families and those students to continue to come here for education is that important.”

This quality is demonstrated in Henriquez’s family, as her parents moved her to Palo Alto so that she could receive a better education, even changing their work shift to the early morning so that her mother could pick her up after school when needed. Fischer’s family has also made sacrifices to maintain a high caliber education for their children. “You don’t choose the family you are with, so you kind of have to make the best of what you have,” Fischer said.

For Fischer, seeing the sacrifices and struggles her parents have endured for her sake has been her biggest motivation through it all. “It has impacted me to try my hardest to achieve more than that (what my parents have achieved), and they have always told me try your hardest and you’ll be what you want to be,” Fischer said.

Opportunities for Success

Because it can be hard for students to identify themselves as low-income and reach out for help, administration has taken measures to de-stigmatize what it means to be from a low-income household. “In our society, talking about money is very off-limits and so it’s hard for people to raise their hand,” Wheeler said. “We try to find ways to make it less stressful and reduce the anxiety of students so they don’t feel excluded, but also make it a caring situation when they do need the support, so they don’t get that negative feeling about themselves.”

Some assumptions about low-income students are that they are primarily from a certain racial group; this, however, is not true. “There is that myth that you are from EPA if you are a certain minority,” Argumedo said. “I’ve had a lot of interactions with some students here who are not minorities and are low-income. And on some levels, it’s very challenging for them. I feel like it is challenging because they are kind of on the out. The students I have encountered are the students that are labeled trouble-makers or they are not like us and people see it as behaviors without really accounting for their lower-income.” According to Argumedo, 36 percent of students in the VTP program are not minorities.

College coordinator Leighton Lang is in charge of helping students prepare for college through the College and Career Center. College Pathways, although not targeted specifically to low-income students, helps bridge the gap between income levels by providing students with resources such as college tours and SAT/ACT prep. “They (College Pathways) have helped me a lot with things about college and getting to know what the college life is like,” Henriquez said. “I obviously can’t say I am going to go across the country looking for colleges, so [the college visits] have been really helpful.”

Wheeler also distributes a fee waiver card, which covers the cost of transcripts, AP tests, yearbooks, dances and grad night. Both Fischer and Henriquez have the fee-waiver card, and have found it helpful in their high school experience.

Lang noted that families can be hesitant to reach out or recognize their need for financial aid. However, once that step is taken, he says, opportunities can become equal to all students, regardless of income level. “If you are low income and you have decent grades, you’ll be just fine; you have the same options as anybody with money,” Lang said. “The school does a great job in making sure that if the student does reach out, they can help them.”

In the face of the growing number of students hiring expensive tutors outside of school, Gunn administration has worked to increase the number of in-school tutoring options. “Flex Time was a response to the idea that people were getting tutors,” Wheeler said. In addition, free tutoring is available after school in the Academic Center to students who request it.

To Argumedo, it is programs like these that have the biggest impact. Acknowledging the challenges and dedication of low-income families within the sea of affluent families in Palo Alto is the first step toward creating a more equal educational system. “There are all these little cuts—they are not huge—but after you get a lot of little cuts, it really hurts and I think that is sometimes what happens to low-income families and it makes it hard,” Argumedo said. “Sometimes there is a big price to pay for opportunities, and I think it is worth it for low-income students. We just have to acknowledge it.”