Written by Kaya van der Horst

A recent crackdown on illegal housing in East Palo Alto has forced the eviction of 40 families from their homes in recent months. Illegal housing is considered to be unsafe secondary dwelling units that violate California Health and Safety Codes.

According to East Palo Alto Mayor Donna Rutherford, the city sent out safety code enforcers to check if residences in East Palo Alto were up to date 12 to 16 months ago. If residences were found to be violating the state’s housing guidelines, code enforcers would then notify the residents and give them a certain amount of time to bring the residence up-to-code. “Landlords that received notices to bring units in compliance with the city’s safety code didn’t do it, which has caused tenants to lose their housing,” Rutherford said.

However, due to a staffing shortage, the enforcement of the safety code came to a sudden halt. In an effort to mitigate this issue, East Palo Alto recently hired two additional code enforcers and the city was able to continue with safety inspections of properties in single-family neighborhoods. Therefore, residents who did not bring their dwellings up to code during the 12-16 month interim are now receiving eviction notices.

According to Rutherford, these families are given a 10 day notice by the city to vacate their premises, causing problems as they scramble to find a new place of residence. “It’s unfortunate that people will have to leave their home and not have a safe place to go,” Rutherford said. “The city is doing everything in its power to help and it’s not going to happen overnight.”

Although Rutherford perceives it as an unfortunate situation, she prioritizes the safety of the residents. “I feel bad about it, but on the other hand I would not like for anyone to end up losing a life because they’re living in an uninhabitable place,” Rutherford said.

Lack of safety

To come to terms with the Bay Area’s high rent prices, East Palo Alto residents rent out their garages or rooms within their house, according to Rutherford. The garages often lack proper ventilation, hot water or kitchens, making them hazardous and uninhabitable. “If you’re in a place that has bad airflow, you could be inhaling mold or fumes, which is detrimental to a person’s health,” Rutherford said.

Junior Jackie Gallegos, an East Palo Alto resident, has observed that several houses in the city are crowded with residents. Gallegos says as many as 10 to 12 people will sometimes occupy a two-bedroom house. “If you drive by East Palo Alto, you’ll notice a lot of houses with many people living in them,” she said. “It’s noticeable because their garage looks different, there are more cars in the driveway and often more stuff is lying outside such as furniture.”

Gallegos has observed that some residents of East Palo Alto have retreated to their cars as a source of shelter, camping out in deserted parts of neighborhoods. “The street that intersects with my street has a couple of trailers and two RV vans,” Gallegos said. “They rotate their cars from street to street in places that don’t look abandoned.”

According to Judy Argumedo, head of the Voluntary Transfer Program, no families within the Palo Alto Unified School District (PAUSD) have indicated being affected by the evictions. “When students leave the Voluntary Transfer Program we ask them for what reasons they’re leaving,” she said. “Sometimes the reasons are because of a transfer to private schools or moving to a different city, but none have been because of the evictions so far.”

However, if a student were to become homeless they would still reserve their right to attend school within in the district. Homeless students would receive McKinney Vento status, which is a federal law that protects homeless children, according to Argumedo. “They don’t just get kicked out,” Argumedo said. “They’re allowed to stay until they get a permanent address.”

Causes of eviction

One driving force behind the increase of eviction rates in the past seven years is the presence of major tech-companies in Silicon Valley such as Facebook and Google. Rutherford says the influx of high-tech money, along with employees wanting to live closer to work has played a large role in the problem. “East Palo Alto is about 57 percent renters and 43 percent property owners,” Rutherford said. “Those are the ones most affected by displacement because of Google and Facebook’s folks buying houses.” In order to combat the inflation of rent prices, the city has a Rent Stabilization Ordinanace to protect tenants from unreasonable rent increases.

According to Rutherford, re-development also contributed to the problem. It was originally supposed to be a solution, intended to increase the city’s tax base. Several apartments were torn down and replaced with the Ravenswood Shopping Center, containing stores such as Ikea, Nordstrom Rack and other major chains. However, while it did bring in revenue, it was at the cost of many people having to move away.

“Gentrification moves people out that have been in a low-income community for a long time,” Rutherford said. “When there’s an influx of new businesses, new housing, it causes folks—especially if they’re not property owners—to have to relocate.”

While gentrification is an issue East Palo is struggling with right now, according to Rutherford, development generates revenue essential to continue providing services for citizens. “How do you keep people who want to be in the city there, and yet encourage development because you need to bring in revenue at the same time?” Rutherford asked. “It’s a really tough situation.”

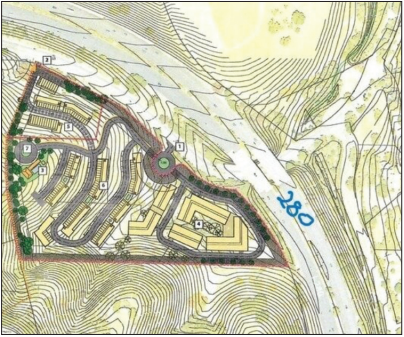

Impacts of drought

In addition to having the lowest median household income within San Mateo County, East Palo Alto receives the lowest distribution of water from the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission’s Hetch Hetchy, according to Rutherford. The huge water shortage has forced a halt on construction of multiple affordable housing units and commercial construction. Until East Palo Alto can negotiate with other cities for an increase in water supply, major projects remain on hold.

According to Rutherford, the City of East Palo Alto does not have an immediate resolution to help displaced families due to the impeding obstacle of water shortage. “The only thing we can do is point them to the resources that are available,” Rutherford said. “Unfortunately, those resources are almost non-existent.”

Churches within the city such as the St. Francis Assisi Church have been assisting families in need by providing food banks and a number of assistance programs. While shelters are an option for adults, they are often full or do not accept children according to Rutherford.

Changing demographics

Census numbers from 2010 show the city is 64.5 percent Hispanic or Latino, 16.7 percent African American and 7.5 percent Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. These numbers prove to be more racially diverse than neighboring towns such as Palo Alto, which was 64.2 percent white and 27.1 percent Asian, according to the same census.

Gallegos also pointed out a change of demographics due to the building of new homes. “There are more people of different ethnicities, such as white or Asian coming to live there,” she said. “The people who live behind me are white.”

East Palo Alto’s rents remain relatively affordable in comparison to other cities. The average rent for a one-bedroom apartment ranges from $1,200 to $1500, while a one-bedroom in Palo Alto costs at least $2,800, according to data from the June 2016 California Apartment List Rent Report.

East Palo Alto’s median household income of $51,916 is a stark contrast to neighboring Palo Alto’s $121,074, yet East Palo Altans face increasing competition from affluent tech employees purchasing homes while they themselves often live a paycheck away from missing rent, according to Rutherford.