By Lena Ye

These are the three most comforting words a student can hear: “There’s a curve.” In most classes, teachers want the average score on a test to be in the mid-80s, so when the mean falls short of the acceptable range, they introduce a curve. Curves are a way to boost grades if the average score is too low, the test is too hard or the class is not prepared. Intended to scale scores and even the distribution, curves are almost always introduced to better students’ grades. Although an easy short-term solution to a flawed test, in the long-run, curves foster unhealthy competition and deter hard work, making them unfair.

Curves inherently cultivate a cutthroat environment and discourage collaboration. A curve is usually calculated from the average and scales all scores up to a desired average, which pits students against one another in hopes of getting a steeper curve. If more people do well and the average is higher, the curve will be lower. Thus, there is little incentive to help other classmates. Studying together might not be as lucrative if it means 10 other classmates will do better on the test, lowering the curve. According to vice president of the Western Association of Schools and Colleges Barbara Davis, students who work in groups develop an increased ability to problem-solve and display a greater understanding of the material. Working in groups improves students’ study skills, and curves hamper this. If teachers use curves on a majority of tests, students will begin to rely on it. Why bother studying for an “A” on a test if you know a “B” will be curved up? Curves nurture laziness. Students can be secure in their low grades as long as they know the rest of the class has failed along with them. In this way, curves encourage lower standards among students.

Moreover, curves make the test fit the students instead of making the students fit the test. Teachers should be able to evaluate whether a class is ready for a test since they do write them; thus, teachers should be teaching the material well enough so that the students are prepared for the assessment, or otherwise write easier tests. If a teacher sends in his or her class to take a test thinking they are ready, and the average score is a “C,” then there are serious issues with the way the class is being conducted. The teacher should be able to evaluate student readiness by introducing smaller assessments.

Despite the fact that students’ grades could potentially suffer, students will sometimes share information about the test with friends who are going to take the test later. There is generally one curve for a test, no matter the class period or the teacher. However, oftentimes earlier periods do much worse on a test than a later period because of this cheating. Even if a student in the earlier period didn’t tell any of his or her friends about the test, they will receive a poor grade on a test that was too difficult for the class, simply because of people who are cheating. Also, a class can be taught by many different teachers who focus on different content. One class might do better than another class on a test simply because the teacher taught material more similar to what was going to be on the test. To have these classes with different teachers or periods graded together is an injustice.

While curves are an imperfect system, alternative options are still necessary for teachers. In a perfect world, teachers would understand their tests and classes well enough that they would be able to ensure, without any alternative methods, that the average would be high enough. However, there are extenuating factors outside of the teacher’s control. Things happen—students don’t listen or do the homework—and averages are not always as high as a teacher would like them to be. Thus, there still needs to be some kind of method to adjust grades; curves, however, are not the answer.

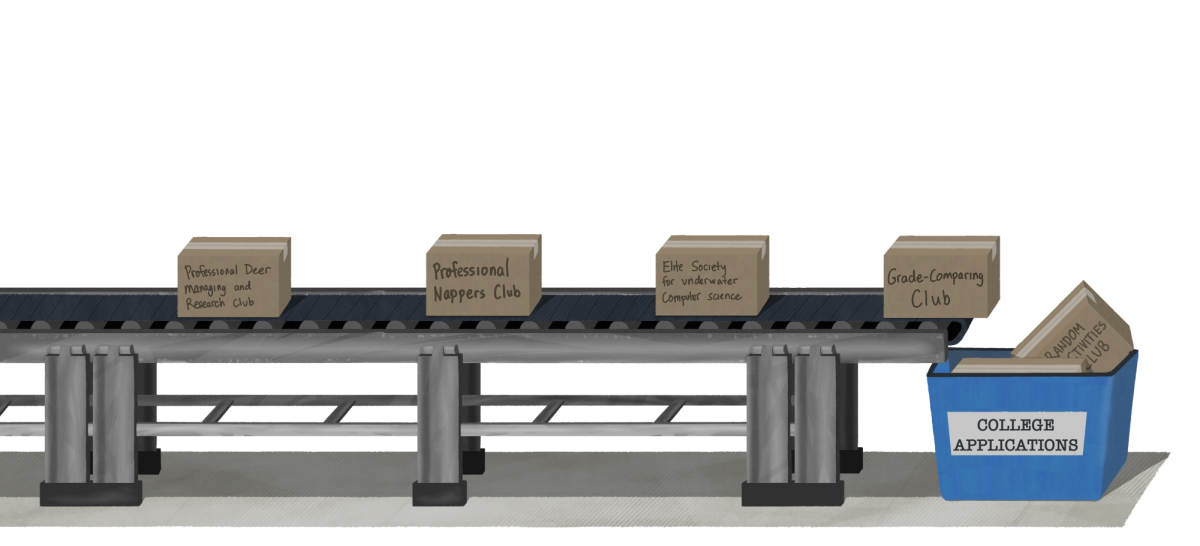

Some other techniques teachers can use are retakes, test corrections or extra credit opportunities. Retakes are quite simple. Some teachers opt to put minimums (only a student with a low enough grade can retake the test), or maximums (students can only improve their scores to a certain point) on them. Test corrections are even more cut and dry. Teachers will usually have students write corrections for the problems they lost points on for partial credit. Some classes utilize a method where the most missed questions on the test are given again as a quiz, and students who get the answer correct will have their score changed on the test. Extra credit opportunities are a bit more uncommon, and there’s a lot of room for improvisation. Ways to offer extra credit can range from giving a presentation on a subject to attending an out-of-school event that relates to the school subject.

Sometimes the average grade does not accurately reflect the class’s ability or knowledge. It’s not fair to students for a test average to be in the low 70s, simply because of a miscommunication between the teacher and the class. That’s not to say that curves are the solution, however—there are many ways to boost grades, most of which are far better than a curve.