The Times They Are A-Changin–Or Are They?

Echoes of past decades have re-emerged, creating striking parallels to recent events.

A young, left-leaning crowd clashes with an overmilitarized police department. Videos of police brutality and arrests flood the news. A moderate Democratic politician is up against a “law and order” Republican politician in a nail-biter of an election season. A beloved civil rights movement figurehead dies, causing the country to confront its racist systems. Sound familiar? Well, don’t think of 2020 so soon—all of those events also happened in 1968. It seems we’ve gone through a year echoing a series of eerily familiar watershed moments: in 1968, protestors clashed with police outside the Democratic National Convention; in 2020, protestors clashed with police at Black Lives Matter protests across the country. In 1968, moderate Hubert Humphrey took on Nixon for the White House; in 2020, it was Biden versus Trump. In 1968, the world lost Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.; in 2020, John Lewis and C.T. Vivian.

Why are there so many prominent parallels throughout history? What leads history to seemingly repeat itself? And, if “those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it,” what’s next for us?

Here are three similarities the 2020s share with the late 20th century; perhaps, through these similarities, we can gain some degree of insight.

Government Distrust

Extraordinary circumstances call for extraordinary leadership. It’s no surprise, then, that the federal government’s dismal response to a raging, uncontrollable disease has inspired mistrust of the government, especially among marginalized communities. Though once again, we’re not just talking about 2020—we’re also talking about the global HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, which has claimed the lives of almost 800,000 Americans, as of 2018.

It didn’t have to be that way.

Dr. Timothy Seelig, the Conductor of the San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus, who is HIV positive and lived through the AIDS epidemic in Texas, is unrestrained in his criticism of the government from that period. “Had the government paid any attention, we would have massively fewer deaths,” he said. “The government didn’t kick in, didn’t even notice [and] wouldn’t even say the word [HIV/AIDS] for so long. And all of the things that we did discover then, the cocktail of medications, and then ultimately a maintenance drug—all of those things could have happened so much sooner.” That negligence planted seeds of distrust in the LGBTQ+ community.

Seelig sees obvious parallels between HIV/AIDS and the current pandemic facing America. Even 40 years later, according to Seelig, the uncertainty at the beginning of a pandemic stays the same. “The early days of COVID were like the early days of AIDS; in the early days of AIDS, nobody knew how you could get it,” Seelig said. “Everyone was afraid to touch anybody or touch anything. People were completely freaked out by touch.”

Seelig also draws numerous distinctions between then and now, specifically with the push for a vaccine. In the 80s, the government stood by idly as AIDS progressed into a global epidemic. This time, they scrambled—the project to create a vaccine was literally called Operation Warp Speed. “The whole world wanted this vaccine; and the whole world wanted this to happen,” he said. “And the whole world wasn’t even paying attention when AIDS became a pandemic. So yes, the loss of life could have been drastically less.”

Since its start in 1978, the Chorus has lost over 300 members to the disease.

Seelig remembers the impact the losses had on him and the chorus. “The chorus was in every stage of grief all the time,” he said. “When you were shocked by a death, and you moved into anger about that, someone else died, and while you were shocked at that one, you’d already moved on to bargaining for the first person. We couldn’t catch our breath. We couldn’t rest long enough to even come up for air and know what was happening.”

It’s not just the LGBTQ+ community; there’s also residual mistrust of medical institutions in the Black community. A recent study released by the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases noted over half of the Black adults in the U.S. are hesitant to receive the COVID-19 vaccine; only 16% of that same demographic believe the vaccine will be distributed equally.

The Rise of New Media

The evolution of media, too, has played a dramatic role in shaping the late 20th century as well as today.

While it’s true that 2020 was mostly downhill from its inception, with the 21st century explosion of social media sites and a 24-hour news cycle, it’s worth begging the question: is more happening, or is the presence of social media just making us hyper-aware of everything occurring in the world? Especially with the pandemic, when screen time has skyrocketed, we have now become more dependent on our devices to keep busy in lieu of human contact, as well as to deliver us a barrage of constant updates, welcome or not.

Along with amplifying stress and anxiety, new forms of media have also fanned the flames of our country’s polarization. “The internet allows us to engage in the ways that are the most seductive to us and our psychologies,” Foreign Policy Honors teacher Tara Firenzi said. “And I think we want to get into arguments; we are drawn to conflict. The internet unfortunately brings out this part of us that explodes things rather than tries to look at them in nuanced and careful and thoughtful and empathetic ways.”

Again, 1968 presents a striking similarity: thanks to the advances of television technology, the Vietnam War was the first war broadcast directly into the homes of the American public. Seeing the horrors of war live and in technicolor strongly shifted public opinion and support for the war. Footage of young soldiers, thrust unwillingly into a pointless war, led anti-war activists

to rally moderates with calls of “Bring back our boys!” Meanwhile, staunch war supporters used those same images to argue marching against the war was an affront to the troops and all they were serving for.

The rise of social media—and social media’s role in shaping the narrative on recent events—has had a similar effect on us in modern times.“I think we are moving more left and more right,” Firenzi said. “Which is probably not the best way forward.” AP United States History teacher Christopher Johnson echoed Firenzi’s sentiment. “There were a lot of conspiracy theorists on social media talking about if this election does not go for Donald Trump, then there’ll be another Civil War,” Johnson said.

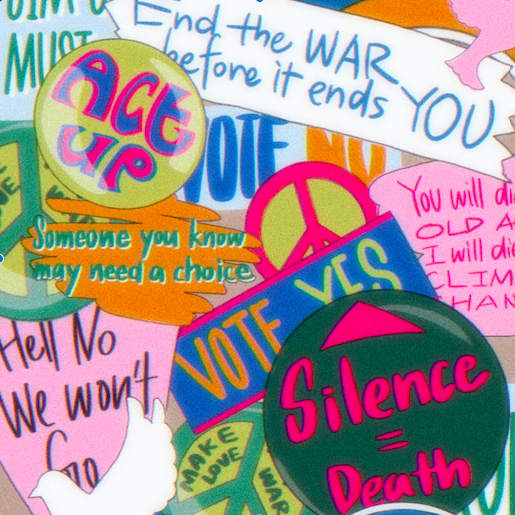

A New Wave of Activism

It was in decades such as the ‘60s, as polarized as they were, that many young people became optimistic, unabashedly idealistic and dared to hope for better. Back then, such individuals were labeled as hippies and famously dismissed by Nixon as a “vocal minority” fighting against the “silent majority.” “Even those more left-wing movements in the US in the 1960s were not a large segment of the population,” Johnson said. “And that’s what conservatives really focused on—the silent majority, those people who

just wanted to keep doing what they’re doing, raise their families, maintain their jobs, and keep a roof over their head, and [who] don’t really want dramatic change.”

In much of the same way, the same phenomenon is still seen today: despite endless vilification of the progressive cause as imminently and unstoppably dangerous by conservatives, the movement is still a small and burgeoning one. For every one breakout, young progressive politician who has successfully overturned a moderate Democrat in a primary election (think Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez), there have likely been tens of cases where such young progressives failed—in fact, now Congresswoman Cori Bush lost her first primary election to moderate Democrat Lacy Clay in 2018 before taking his seat in 2020.

Youth-led groups are often ridiculed for being idealistic, or being naive. Where have we heard that before? “I think that the big mistake that has been made, generation after generation, is the immediate reaction of dismissiveness [to deviations from the norm],” Johnson said. “So the younger generation comes up with an idea. And the old ones say, ‘Oh, no, that’s never gonna work.’ Well, how do you know until you try?”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Henry M. Gunn High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.