Affordable housing scarcity impacts staff commute times

On a typical weekday, English teacher Kate Zavack begins her morning at 6:00 a.m. at her home in Gilroy, 48 miles away from Gunn. She scrambles to brush her teeth, get dressed, cook lunch and load the car before her son Jude wakes up. By 7:15 a.m., the two are on their way to Jude’s preschool in San Jose, 33 miles away from Gilroy. After dropping off her son, Zavack continues to drive another 20 miles before arriving at Gunn at around 8:30 a.m.

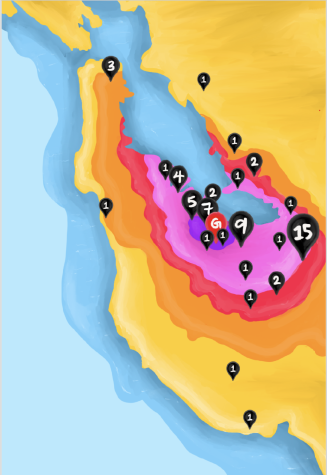

As housing across the San Francisco Bay Area continues to rise to unaffordable costs, Zavack’s morning has become less of an anomaly and more representative of the work-life balance for the average Gunn teacher. From a survey sent to staff with 76 responses, the most common wake-up time is 6:00 a.m., with the earliest reported wake-up time at 4:30 a.m. from a staff member commuting more than 90 minutes from Roseville. Arrival times on campus vary more, with the most common arrival time at 8:00 a.m.

The San Francisco Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR) identifies two key factors driving the housing crisis: a decrease in the number of new homes being built and the widening gap in income inequality. In recent years, local governments have placed more restrictions on developers in the interest of protecting open spaces and single-family zoning. At the same time, median house prices in the nine Bay Area counties reached $1.34 million in May 2021, an increase of 38.9% from 2020, according to the California Association of Realtors.

Meanwhile, teachers’ wages have not increased by a commensurate amount, making it more challenging to live close to work, according to dance teacher Tara Firenzi. “The real problem is that we don’t universally pay teachers enough to live in the communities that they teach in,” she said. “Even in Santa Cruz, a lot of teachers live in places that have a lower cost of living because they’re not paying teachers enough in Santa Cruz to actually live there.”

As a result, most teachers live in cities far from Gunn, facing a long commute to work every day. According to the staff survey, 52.6% of the respondents had a commute of under 30 minutes, while 39.5% drive 30 to 60 minutes and 7.8% drive more than 60 minutes to get to work.

Trade-offs to long commutes

While frustrations are unique to each educator, their experiences all carry a similar tune of imbalance: location or commute.

Many, including AP Economics teacher Phillip Lyons, cannot afford to live near Gunn. “I could not move down to Palo Alto,” he said. “It wouldn’t be financially possible to buy a home down here. I have a wife and two kids, so I was lucky to get a place 20 years ago in [San Francisco], where we have a small apartment.”

School psychologist Melissa Clark also views finances as a major limitation. “[My family] owns our house,” she said. “If we looked at moving now, our mortgage would go up a lot. That’s a huge factor.”

Additionally, longer commutes have forced teachers to make significant sacrifices. Firenzi shared frustrations about her longer commute. “It bothers me how it’s hard for me to be present at extracurricular activities for my students,” she said. “I’d really like to show up sometimes for games or theater events, but I can’t stay late into the night. I have to go home first and pick up my kids and do what I need to do. It keeps me from being present here.”

For Para-Educator Radhika Thampuran, the current housing arrangement takes a significant toll on her energy. “Mornings are fine, but on the days where the schedule ends at 4:10 p.m., I reach my home at around 5:30 p.m.,” she said. “As winter [approaches], it gets dark by the time I reach home, so I don’t have any energy left to do anything.”

In order for teachers to avoid the consequences of long commute times, however, many would have to sacrifice their quality of life. “I chose the neighborhood we’re in because I have a son and I want him to be able to go play outside and ride his bike on a nice, quiet street—not next to a freeway and not in a tiny apartment complex,” Zavack said. “When I think about the quality of life in terms of not being so cramped, that’s a huge factor for me.”

COVID-19 and the present

Last year, online learning temporarily gave teachers a taste of life without the daily commute. For Zavack, this meant more time for relaxation and self-care. “Being able to have that extra 30 minutes a day to go work out or take a class that interested me made a big difference,” she said. “Even just being able to go sit out in my backyard at the end of the school day and decompress really made a difference.”

Lyons also enjoyed the newfound time, which he dedicated to family bonding. “With my kids at home, we spent so much more time together,” he said. “I went to the park almost every single day to play with my kids,” he said. “Now, I get home, and it’s already pitch black. I can’t do those things anymore.”

Like Lyons, most teachers no longer have the time to engage in familial activities due to the return to long commutes. Starting this school year, the district implemented a new bell schedule with a start time of 9:00 a.m. and end times ranging from 3:30 p.m. to 4:10 p.m. While this shift was meant to encourage more rest for adolescents, it also forced teachers into the middle of rush-hour congestion. “Two extra hours a day on the road kind of wears you out,” Lyons said. “Even though you’re just sitting passively in a car, it’s stressful to be in traffic and have people honking and cutting you off. It’s a draining experience.”

The inconvenient schedule has led to some, like Special Education Teacher Briana Gonzalez, to spend more time at Gunn. “To beat the traffic so I’m not sitting bumper to bumper on the [Dumbarton] Bridge, I actually stay on campus a little bit later just to make sure my commute home isn’t as hectic,” she said. However, this option is not accessible for teachers with families and other commitments after school.

Current solutions

Santa Clara County and other participating school districts have begun one project to ameliorate the housing shortage: the construction of 100 residential units at 231 Grant Avenue in Palo Alto. Although the initiative will not be completed until 2024, PAUSD Board of Education President Shounak Dharap expressed enthusiasm about the project. “The Board showed support in the discussion about investing in the county’s teacher housing plan and seeking as many available units as possible,” he said. “If the Board moves forward and approves the contract, this should help alleviate some of the pressures of housing costs in the area.”

However, this new housing initiative has limitations and isn’t practical for those like Clark who need space for their families. “There’s no way I could convince my spouse to move into a small condo,” she said. “The size of our current house is not huge, but there’s room to breathe.”

Another group working toward more obtainable educator housing is the United Educators for Housing and Literacy (UEHL), a non-profit organization that focuses on drafting public policy to make teacher housing more affordable. The group promotes a federally funded Basic Allowance for Housing (BAH), which would supplement teachers’ salaries for housing purposes.

Changes necessary

Ultimately, the problem of educator housing extends beyond PAUSD and requires regional—if not national—action. “The only permanent solution is sustained investment at the city, county and state level in affordable housing and public transportation,” Dharap said. “Investment in the county’s housing project is a great first step in this regard, at least until more permanent solutions are put into place.”

However, Firenzi points out that subsidized housing is only a temporary solution. “Teachers need access to capital, and they need to be able to establish themselves in a way that allows them to live an average life in that community,” she said. “That’s a problem way bigger than Palo Alto, but it’s how we conceive of what teachers are worth, what teachers should be paid and what they should have to sacrifice.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Henry M. Gunn High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Senior Chris Lee is a managing editor for The Oracle and has been on staff since August 2021. In his free time, Chris enjoys driving, going out for food...

Sophie Fan, a senior who has been on staff since Jan. 2020, is the graphics editor for The Oracle. When she's not handing out graphics assignments left...