Public school enrollment declines as students move out of state, opt for other mediums of learning

Since California’s admittance as the 31st state, it has served as a progressive model for public education. Schools became free for all students in 1867, California was one of the first states to pass a compulsory attendance law in 1874 and the Golden State enacted the Class Size Reduction Program in 1996, which aimed to have 20 or fewer students in kindergarten through third grade classrooms. These actions ultimately led to the state’s public school enrollment increasing by more than a million students—22%—between 1993 and 2004.

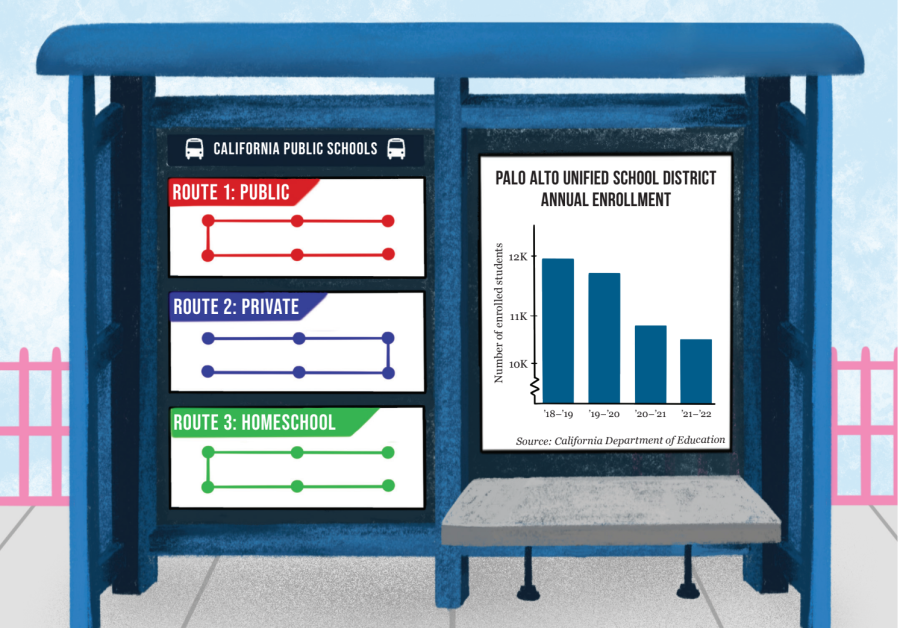

However, recent trends have shown a reversal to this growth. Out of the state’s 58 counties, 53 experienced a decline in student populations during the COVID-19 pandemic, with public school enrollment falling 2% since the 2019–2020 school year. According to the California Department of Education, Bay Area public schools have lost 6.5% of their students, with Palo Alto Unified School District (PAUSD) seeing a 10.5% decrease in students since 2019.

Impacts on Enrollment

Pandemic-era learning has led some students and their families to reconsider public schools. Junior Ella Holsinger, a student at the Castilleja School, attended Gunn for her freshman year before enrolling in private school as a sophomore. “The distance learning that Gunn did [at the end of] my freshman year was pretty sparse,” she said. “We didn’t have to go on Zoom calls and the asynchronous work didn’t benefit me at all. Ultimately, my family and I made the decision to go [to Castilleja] together.”

According to Assistant Principal Courtney Carlomagno, public schools faced more barriers than private schools when it came to adapting throughout the pandemic. “Public schools are larger than most private schools so sheer size can cause protocols to be larger to manage,” she said.

Parents and students began to notice the different transition protocols offered by private and public schools, including their hybrid options and dates for full in-person instruction. “I went back to [in-person school] in Nov. 2020,” Holsinger said. “[At Castilleja,] we ended up going to a model where it was one week of online and one week of in-person which was amazing.” In contrast, PAUSD high school students were not offered a consistent in-person learning option until March 2021, in which they could choose to come on campus for two days of the week.

Other students such as sophomore Zefan Feng chose to move to private schools for reasons outside of pandemic restrictions. “The student-teacher ratio was quite important,” he said. “There are around 40 kids per grade [at the Pinewood School] so we have more individual attention from the teachers. I think that it’s easier to get better grades if you have more attention.”

Although private schools are a factor in declining public school enrollment, they themselves have also experienced dropping student populations, indicating that they aren’t the primary cause for the exodus from public education.

Another main contributor has been California’s overall decreasing population. According to the California Department of Finance, the state lost 117,600 people in 2021, with the San Francisco Bay Area population declining by 50,400 people. Although the region only makes up 19.4% of California’s population, it accounts for 42.9% of the decline statewide.

Many, including English teacher Diane Ichikawa, point to the area’s comparatively high costs of living and pandemic trends as the reason why people are leaving in record numbers. “There are a precious number of people who can actually afford [to live] someplace like Palo Alto, let alone any of the coastal regions in California,” she said. “The ability for people to work remotely made it so that people could live in places like Montana while still making the same kind of money that they would [make] if they were in California.”

According to the Public Policy Institute of California, most families have relocated out of the state for housing, jobs or family-related reasons. Junior Riku Sakai moved to Gilbert—a suburb of Phoenix, Arizona—during the summer of 2020. “[We moved] mostly because of my dad’s job and also our financial situation,” he said.

However, some, such as sophomore Julie Chen, have used moving as an opportunity to take advantage of alternative academic pathways. “We decided to move to Bellevue, Washington partly because of the International Baccalaureate (IB) program [offered there],” she said. The IB program is a rigorous, two year course of study that culminates in a student receiving an internationally recognized diploma. PAUSD currently does not offer an IB program at either of its high schools, and there are no plans to implement one in the near future.

Another trend amplified by the pandemic is homeschooling. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau shows that 5.4% of families reported choosing this option in the spring of 2020, compared to 11.1% in the fall of 2021.

Sophomore Justin Lee decided to try homeschooling instead of attending Greene Middle School for his eighth grade year. “My mom wasn’t working at the time so homeschool was eventually an option that we started to consider,” he said. “As an eighth grader, I was able to love learning again. If I had known at all how homeschool [was before], I don’t think I’d have ever chosen to go to public school just because I like it so much.”

Even before fully transitioning, Lee’s family had some experience with learning at home. “Almost every summer, my family would do a version of homeschooling, and I would follow a curriculum developed by the homeschool community,” he said.

Funding Consequences

The California state government establishes a funding goal—known as the Local Control Funding Formula—for how much money a district should receive per student enrolled. If the area’s property taxes are insufficient to provide the necessary funding, the state comes in to cover the shortfall. While most schools are funded through a combination of state and local revenue, around 8% of districts—including PAUSD—are considered basic aid. Basic aid districts are areas where property tax revenues exceed the funding threshold set by the government, meaning that they receive minimal state funding.

Because property taxes do not fluctuate based on how many students are enrolled, declining student populations have had few financial impacts on districts like PAUSD. However, those relying on the state for revenue have had to make some difficult choices, since their funding is determined by enrollment. According to district records, Alum Rock Union School District in San Jose decided to merge two middle schools after losing over 1,000 students since the 2019–2020 school year while West Contra Costa Unified School District currently faces a $24 million deficit and is looking to cut staff and student programs.

At Gunn, the decrease in students has still led to noticeable impacts, according to Social Studies Instructional Lead Jeff Patrick. “For the last couple of years, there’s been a steady decline of students,” he said. “The interesting thing is that it’s not just a smaller incoming freshman class, each of the grade levels are losing students. Next year’s 12th grade class is smaller than this year’s 11th grade class, meaning that not all of the students are coming back.”

Even though PAUSD doesn’t face the same dire consequences as other districts, Ichikawa points to initiatives that could help retain students. “PAUSD doesn’t even have to shrink in terms of its number of teachers and the resources that we have,” she said. “We have millions that are locked away in our reserves and we’re not going to go poor over everything that’s happening. We can use this as an opportunity to have smaller class sizes and more arrays of programs to find a really good fit for our changing population.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Henry M. Gunn High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Senior Chris Lee is a managing editor for The Oracle and has been on staff since August 2021. In his free time, Chris enjoys driving, going out for food...