‘The math wars have casualties’: Conflicts over math permeate district, fuel debates over equity, accessibility

In response to a lawsuit brought by parents in 2021, Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Carrie Zepeda filed a court order on Feb. 6 determining that Palo Alto Unified School District’s method of placing students in math courses violates the Math Placement Act of 2015. Those filing the lawsuit charged that PAUSD failed to “systematically take multiple objective academic measures of pupil performance into account” when determining math placement, relying solely upon a student’s course in the previous year to determine placement for the next and offering little to no recourse for students who feel they have been misplaced. Zepeda ruled in the parents’ favor and ordered PAUSD to adopt a placement policy using objective measures, collect and report data regarding placement and assign a placement checkpoint during the first month of the school year, among other requirements.

Despite extremist proposals (and mandates), there is a rational middle ground, and many teachers seek it…The math wars have casualties—our children, who do not receive the kind of robust mathematics education they should.

— Berkeley professor Alan Schoenfeld

A month later, on March 20, San Francisco Unified School District parents filed a lawsuit on the district’s math placement policies. The same day, researchers from Stanford University had shared the results of a study showing that SFUSD’s delaning initiative—which proposes that all students begin with Algebra 1 in ninth grade—was not increasing representation of Black and Hispanic students in advanced courses, contrary to the program’s initial goals.

These events are just the latest battles in Silicon Valley’s “math wars.” Over the years, parents, students, educators and administrators have participated in a tug-of-war over how math classes and pathways should be structured, who is being represented and what is being taught. Through looking at these past developments, we can better understand the conflicts of the present day.

The root of the problem

Starting in the 1960s, “new math” took the nation by storm. According to a 1974 New York Times article, its purpose was “to stress the whys rather than the how’s of mathematics, and to deemphasize the drill and rote learning that had been the substance of traditional mathematics education.” In PAUSD, schools such as Ohlone Elementary School were set up in response to the open education movement, which utilized these new pedagogical methods. In 1974, some parents pushed the district to open Hoover Elementary School as a “back-to- basics” option for students, emphasizing traditional modes of teaching math.

The issue reemerged in 1995. After PAUSD classrooms adopted reforms, including group work and student-led problem solving, a group of Palo Alto parents formed Honest Open Logical Debate, an organization advocating for traditional mathematics over new methods. In 2009, the district adopted the elementary school curriculum Everyday Mathematics despite a petition signed by 700 residents urging the district to reconsider what they saw as a curriculum lacking rigor.

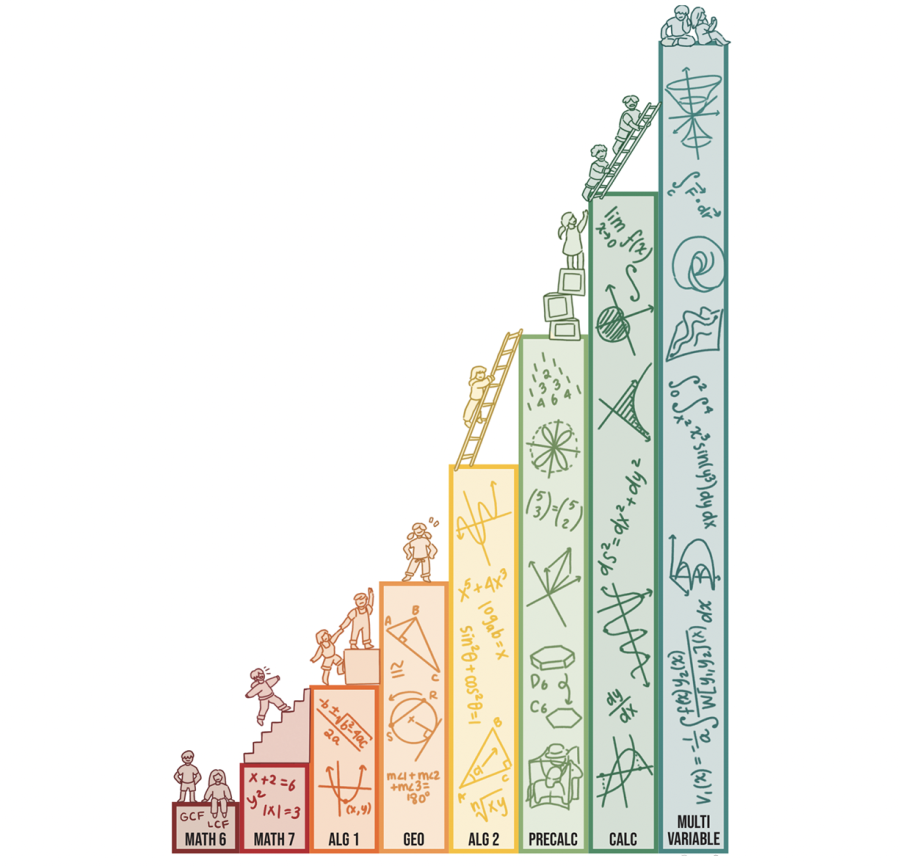

More recently, in 2019, amid heated debate, PAUSD middle schools were delaned so that all students would take Algebra 1 in eighth grade. In 2021, after the publication of the new California Mathematics Framework, the Golden State made national news. The framework—which deemphasized calculus, recommended Algebra 1 for ninth grade and encouraged the use of math to “explore mathematical ideas…in a social justice context”—was met with strong opposition from many. It is still undergoing revision as of April 2023.

Integrating all students

At the heart of all these math controversies is a disagreement over what an equitable and effective high school math education looks like. PAUSD parent Avery Wang, who successfully sued PAUSD over his child’s math placement in 2020 and serves as an advisor for the plaintiffs in the current lawsuit, believes that the flaw in PAUSD’s system lies in its emphasis on equality of outcome, rather than opportunity. “We’re seeing that high achievers are being held back, and then the kids who are behind are being pushed forward,” he said. “We’re talking about kids who are (far) below grade level suddenly being pushed forward to algebra, and then you have other kids who have (learned) algebra a couple of years ago, all in the same classroom.”

Wang has felt frustrated with PAUSD’s lack of transparency with placement data, pointing in particular to the “skip” test, an option offered to students at the end of fifth, sixth and seventh grade which allows those who pass to advance a year in math. After obtaining data from PAUSD through a public records request, he found the placement process in 2021 included questionable practices. While only three students met the criteria to skip a grade—scoring greater than 80% on a Schoology assessment and performing well on all “critical levels” on the Mathematics Diagnostic Testing Project—another 14 were granted a “pass.” These 14, however, were not the next highest scorers: A student scoring 56.25% on the Schoology assessment and a 42 on the MDTP passed the test, while another scoring 70.83% on the Schoology assessment and a 42 on the MDTP did not. According to Wang, the district did not respond to his queries regarding the discrepancy.

Junior Benjamin Vakil, who has repeatedly attempted to skip a grade of math, was also vexed by the skip test administration. “I didn’t know how to study for it,” he said. “I had an individualized education program at the time—I had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder—so I wasn’t able to prepare for it.”

Some math teachers, however, including Math Instructional Lead David Deggeller, point to increased pressure on students when more options for acceleration are provided. “The moment we put multivariable calculus on our pathway, that’s (now) the highest class—so now I guess MIT wants you to get there, and it’s just going to double down the pressure to get to that class,” he said.

Multivariable calculus has since been removed as a dual enrollment class at Gunn. Superintendent Don Austin initially cited the lawsuit as the cause for the course cancellation, but subsequently clarified at the school board meeting on March 28 that it was the lack of a credentialed teacher. Deggeller noted that the course has not had a PAUSD credentialed teacher in over a decade.

Still, lawsuit plaintiff Edith Cohen feels that educators’ and administrators’ assumptions about parents placing excessive pressure on their children stem from a lack of connection with the community. “The attitude is, ‘These kids that are doing academics outside of schools are cheating (and) are being abused by their parents,’” she said. “You can hear it from the people speaking at board meetings, or even the board members. It’s, ‘We would not do that to our kids. Therefore, it’s not right for you.’”

Because of this dynamic, some parents have found it difficult to communicate with those at the district level. “(There is a) complete cultural disconnect, and (the district is) projecting their own biases on people that come from very different places,” Cohen said. “It’s a huge power for the school district—especially with the students that are children of immigrants—and that power is being abused.”

(The teachers) want to support you, but they don’t really understand fully how the student could feel.

— Sophomore Amy Torres

Some take issue with all of these arguments, noting that they divert the focus from students who are struggling to those who are already excelling. Math teacher Daniel Hahn felt that this dynamic was present in the current lawsuit. “My understanding of the (Math Placement Act) was that it was introduced to help the students that were struggling, the disadvantaged students, get a fair shot at being in the mainstream,” he said. “(But) in the wording of it, it says every student should be placed according to their level—it’s pretty subjective as to what the student’s level is.”

Sara Woodham, founder of Parent Advocates for Student Success—a group advocating for improved outcomes for historically underrepresented students— voiced a similar sentiment at the March 28 school board meeting, pointing out disingenuity in arguments for more advanced pathways in middle school. “With 68% of Black and brown ninth graders not meeting our district goal of any geometry level this year, conflating lack of representation of (historically underrepresented) students and skipped math classes as an equity issue is naive or wilfully ignorant,” she said.

Because of this conflation, students’ struggles with non-accelerated coursework are sometimes disregarded. Sophomore Amy Torres, who took algebra in eighth grade, again in ninth grade and is taking it again this year, finds this disconnect apparent in her classroom. “(The teachers) want to support you, but they don’t really understand fully how the student could feel,” she said. “The student could be struggling in class, (still) not understanding a subject that (could) have been learned years ago.”

Still, Cohen notes that raising the floor and the ceiling aren’t mutually exclusive: Other districts, such as Cupertino Union, utilize middle-school laning, but their economically disadvantaged students have outperformed PAUSD’s on the California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress. In the 2021-2222 school year, PAUSD reported around 30% of economically disadvantaged middle schoolers meeting or exceeding standards, while Cupertino Union reported 60%.

District officials, when contacted about the math curriculum, either did not respond or said they could not comment due to the pending lawsuit.

A critical point in the debate

These debates over equity come amid the backdrop of national pedagogical disputes in mathematics. In April 2022, the Florida Department of Education rejected 42 math textbook submissions because they were found to “incorporate prohibited topics or unsolicited strategies,” including “references to Critical Race Theory (CRT), inclusions of Common Core and the unsolicited addition of Social Emotional Learning (SEL) in mathematics.”

Similar controversy broke out after the aforementioned 2021 California Mathematics Framework was released. An open letter signed by over 1,000 STEM professionals found that the framework had a counterproductive approach. “For all the rhetoric in this framework about equity, social justice, environmental care and culturally appropriate pedagogy, there is no realistic hope for a more fair, just, equal and well-stewarded society if our schools uproot long-proven, reliable and highly effective math methods and instead try to build a mathless Brave New World on a foundation of unsound ideology,” it reads.

There is a complete cultural disconnect, and (the district is) projecting their own biases on people that come from very different places. It’s a huge power for the school district—especially with the students that are children of immigrants—and that power is being abused.

— Lawsuit plaintiff Edith Cohen

Wang believes that PAUSD has been adopting this mindset in no large part due to the influence of Stanford University Graduate School of Education professor Jo Boaler, a controversial figure in mathematics education whose research methods have been questioned on multiple occasions. Boaler helped author the aforementioned 2021 California Mathematics Framework, and her research was cited to support PAUSD’s delaning initiative in 2019. She is also the co-founder of YouCubed, an organization that currently provides the curriculum for PAUSD’s Introduction to Data Science course. Wang added that Boaler’s pedagogical approach is not supported with statistical evidence, citing faulty data from SFUSD influencing the California Math Framework. In one instance, the data claimed that delaning decreased the repeat rate of Algebra I from 40% to 8%, but parent advocacy group Families for San Francisco used data obtained via public records requests to determine that this rate drop could be attributed to an elimination of a course exit exam previously required to pass the course, not just delaning.

According to Vakil, rather than emphasizing reformed pedagogy, classes and pathways restricting advancement for some students, the district should work to raise the ceiling for everyone. “What they should be focusing on is getting people of color, people with disabilities, people who like math but aren’t in (higher level math) and people who live in poverty who like math and could excel in math, into these higher-level math lanes and give them the supports necessary to succeed,” he said. “That would be how you should apply social justice to math.”

Solving the equation

The “math wars” have become a microcosm of political polarization in the nation as a whole, as is evident from the controversy over Boaler’s policies and the rejection of the math textbooks in Florida. Fletcher Math Instructional Lead Becky Rea noted that this disconnect can remove nuance from an issue such as math education. “Our country in general has become really party-lined politically,” she said. “I feel like there’s a lot of thoughtful people that go, ‘Well, there are pieces of this that I agree with and pieces of that,’ and that is becoming harder— having (people) that fit into multiple categories.”

The need to surmount these divisions is clear: According to Berkeley professor Alan Schoenfeld, who chronicled these conflicts in an article titled “The Math Wars” published in the journal “Educational Policy,” those harmed by these math wars too often end up being the students. “Despite extremist proposals (and mandates), there is a rational middle ground, and many teachers seek it,” he wrote. “The math wars have casualties— our children, who do not receive the kind of robust mathematics education they should.”

In light of these consequences, Rea finds communication to be the best solution. “I get how hard it must be to (think), as a parent, ‘I know what my kid should have and you’re not giving my kid what I think my kid should have,’” she said. “It’s got to be hard, (so) I always want to have those conversations and get the emotions down.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Henry M. Gunn High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Senior Amann Mahajan is the editor-in-chief of The Oracle and has been on staff since January 2022. When she’s not reporting, she enjoys solving crosswords,...

Aritra Nag • Aug 2, 2023 at 2:34 pm

Thank you for your well-researched and objective article. It will go a long way toward explaining what’s going on with the math wars in PAUSD.

Monica • Apr 26, 2023 at 2:39 pm

Wow, this is an impressively researched and well written article