During a family reunion in 2017, freshman Samantha Knudson was drawn to her grandmother’s beautiful mass of intricately braided purple hair. This moment marked a turning point in how she viewed her own hair.

“I was around 7 or 8 at the family reunion,” Knudson said. “I knew that protective hairstyles like braids came from the African American side of me, but I hadn’t been able to see it a lot, so seeing them on my (family) was really cool.”

Growing up in a predominantly white and Asian community, Knudson rarely saw hair like hers. Because her mom wasn’t educated on how to care for Black hair, either, Knudson didn’t have guidance on how to maintain her hair. She ended up following her peers’ routines, though they didn’t suit her hair type.

“I washed my hair every other day, which you’re not supposed to do,” she said. “That’s far too often for hair like mine. Most of the time, I put it in a singular braid because that’s what I saw a lot of other people my age doing.”

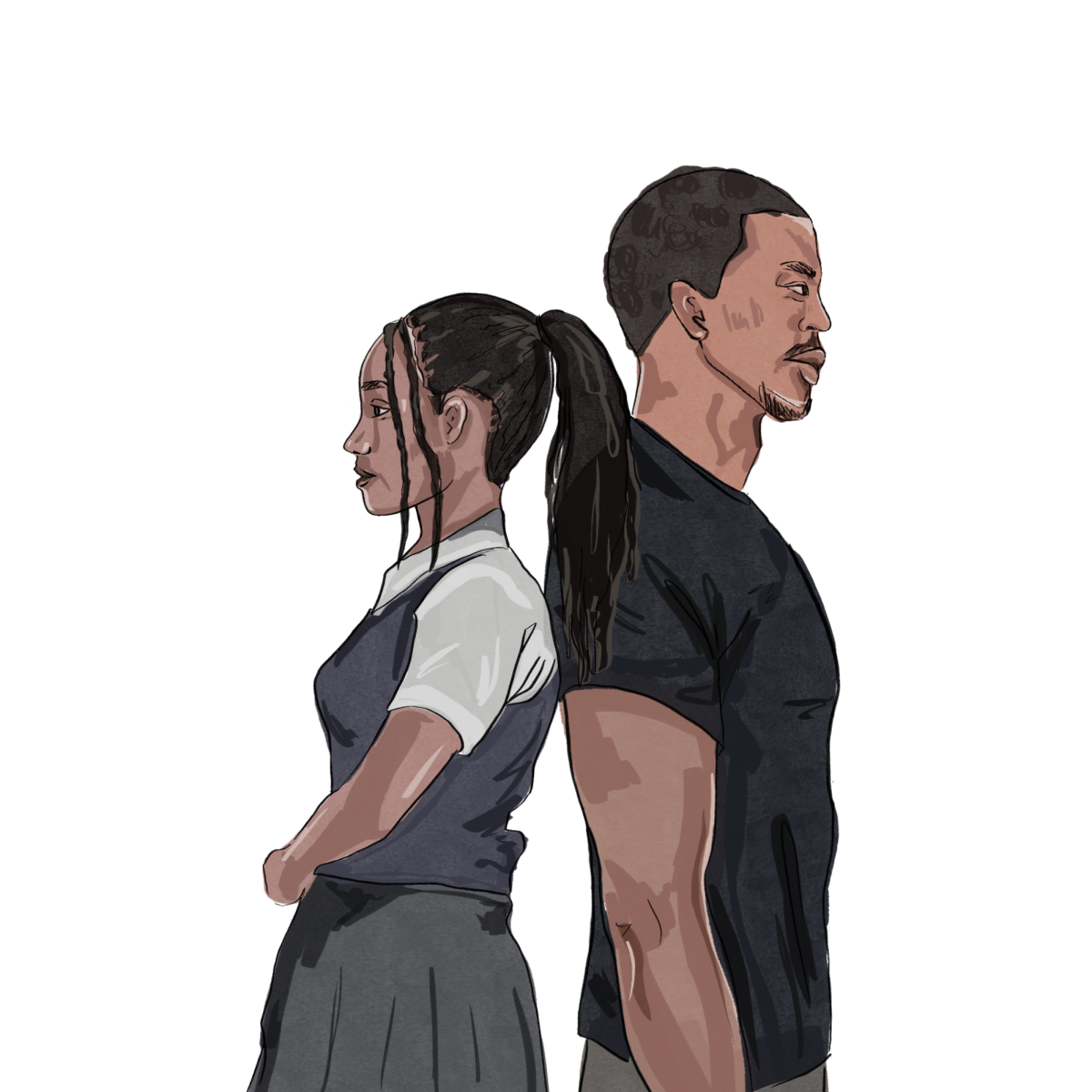

Knudson’s experience isn’t anomalous: Many students have struggled to maintain hair that doesn’t adhere to Eurocentric norms. Sophomore Elijah Williams, for example, described never having advice on how to take care of his naturally curly hair. Worried that he would be stereotyped, his grandmother urged him to keep his locks short.

“My grandma was really big on taking care of how people perceived me,” he said. “Growing up, she didn’t want me to look like a ‘thug,’ so she usually made me buzz my hair.”

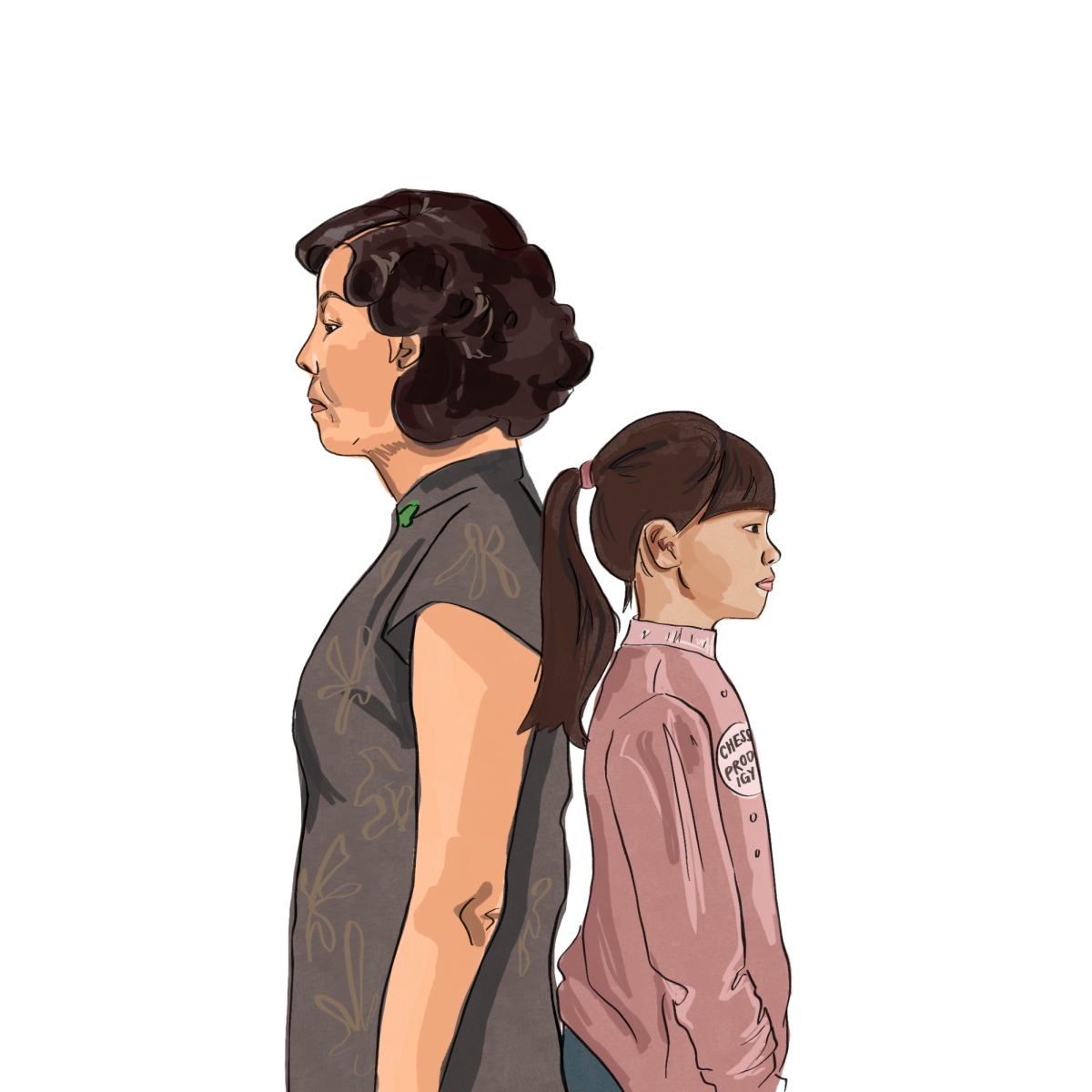

Raised in an Indian community in Spain, senior Angelina Rosh’s self-image was shaped by cultural biases.

“In the Indian communities (in Spain) that I grew up in, everybody brushed out their curly hair to make it frizzy — nobody knew how to take care of their hair,” Rosh said. “The standards in Indian culture are Eurocentric, so straight hair is considered prettier. I always internalized it as (me) having really ugly hair. I hated my hair.”

When Rosh moved to the U.S., she encountered more diverse hair types but still felt restrained by the beauty standards in her Indian community.

“I go to an Indian church,” she said. “That’s where it proliferated. The Indian community I was in maintained the same values that the mainland does, which is that straight hair is prettier. All the aunties would make passes at my hair.”

Still, students like Rosh have carved out their own methods of self-care over the years. While Knudson didn’t dedicate much attention or care to her hair at first, she reevaluated her routine after seeing her grandmother’s hair at the reunion, experimenting with new hairstyles to restore her hair’s health. Her go-to during this time was straight down — no up-dos — because pulling her hair back into tight ponytails and braids like her peers’ had damaged it.

Similarly, Williams experienced a perspective shift at the beginning of eighth grade, when he got a haircut that didn’t suit his hair. Wanting to be able to feel good about himself and look his best, he believed that growing out and learning more about his hair was essential.

“I didn’t want (my hair) to be really unhealthy,” he said. “I just didn’t know how to fix it. I resorted to social media, and then my brothers also helped me a lot. I just kind of experimented.”

Rosh also gave herself time to explore new hairstyles during the pandemic. Through TikTok and other online posts, she curated a hair-care routine that restored not just her curly hair, but her self-image.

“The pivotal point was walking into church again, and an auntie that had made fun of my hair before (asked) me, ‘Oh my goodness, how do you do your hair?’” Rosh said. “I told her, and then I told her daughter. Now, her daughter has healthy curly hair and she knows how to take care of it.”

After instructing some other church members on how to take care of their curly hair, she began to teach her mom as well.

“I held so much judgment against her for not knowing how to do my hair, but then doing my mom’s hair and teaching her how to do it really felt like a generational breaking point,” Rosh said.

Rosh has enjoyed being an educator and advocate for those with curly hair. Now, both she and her mother embrace their culture through their hair maintenance.

“Putting energy (into) and prioritizing taking care of my hair makes me feel more connected to my culture — whether it’s oiling my hair or having my mom oil my hair — which is a big love language for us,” she said.

By the time Knudson graduated from middle school, she had also decided to change the way she styled her hair to better reflect her cultural background and artistic desires.

“I started to care (more) about my appearance, not only because other people saw me, but because I wanted to look the best for myself,” she said. “I planned to show a different side of me when I got to high school. I wanted to express and experiment with myself in artistic ways, and my hair was one of them.”

Knudson’s first protective hairstyle entering high school was braids, inspired and done by her grandmother. When 2024 began, however, she tried a new style: two-strand twists called passion twists, which she currently wears.

According to Knudson, getting her hair done was a time-intensive process: Cornrowing, looping in extensions, crocheting and twisting took two to three hours. Still, it was worth it — after the passion twists were finished, Knudson returned to school with yet another part of her culture that she could share with others at school. “In (Gunn), you don’t see as many people with protective hairstyles,” she said. “(My hair) helped me expose myself and have people see different sides of me.”

Embracing her unique hair — alive in her grandmother and embedded in her ancestry — has given Knudson a profound appreciation for her identity.

“Learning about my hair and being able to express myself through it (has) helped me be closer to my Black roots,” she said. “I can see a different side of me that I haven’t been able to before.”

Likewise, Williams expresses his pride in his Black culture and carries this pride with him through his hair.

“I like to represent being Black, especially in areas where we’re a minority,” he said. “I feel like through my hair, I can do this.”