Most high school students active on social media platforms can recall, at one point, having seen a congratulatory college athletic-recruitment post. Some show athletes dressed in the merchandise of their new college or university, while others share personalized video announcements or posters. These students have been recruited to play sports at the collegiate level — the ultimate and often difficult target for many high school athletes.

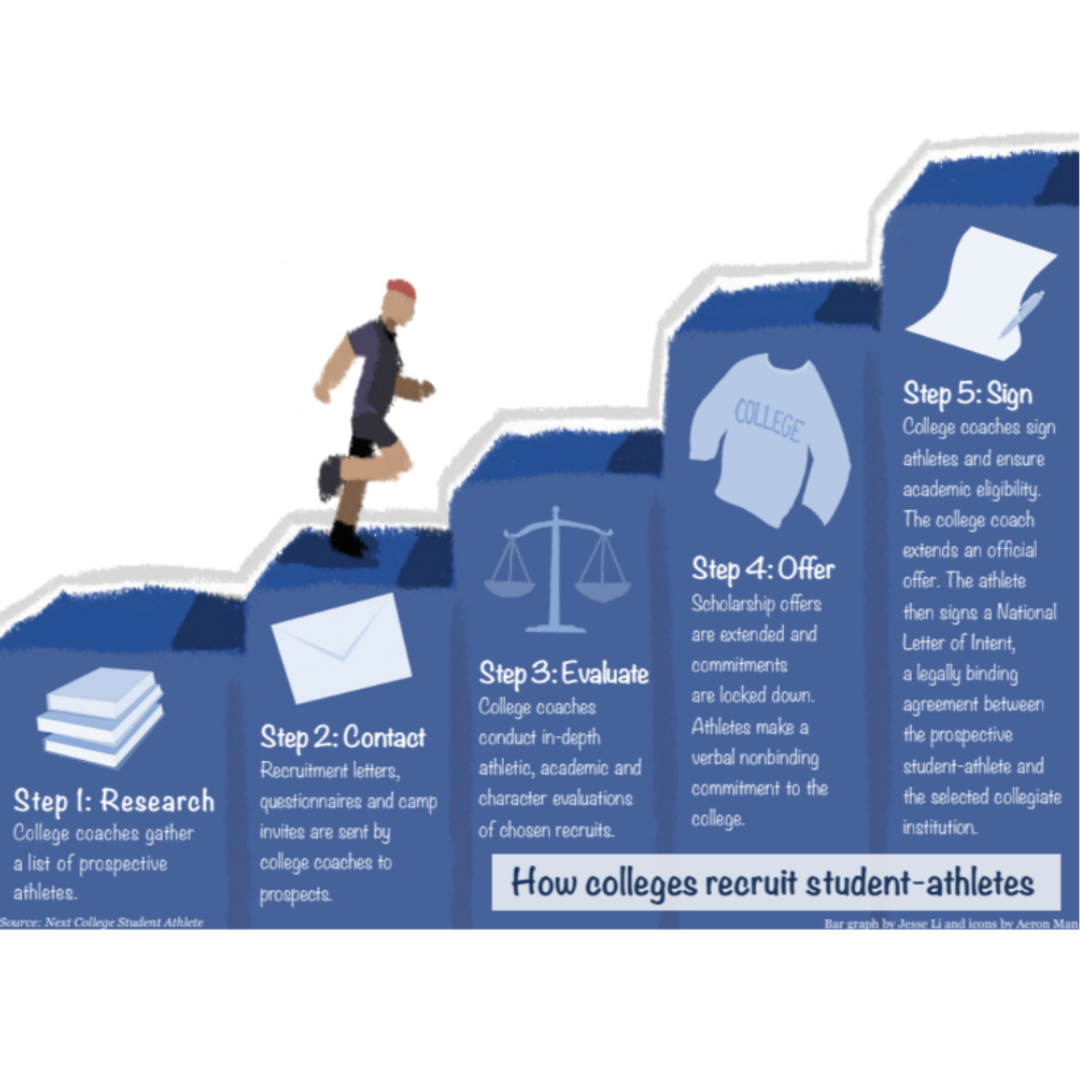

The recruitment process relies primarily on one individual’s work: the athlete’s. Athletes seeking recruitment hope to gain colleges’ attention through attending showcase events, sharing statistics and highlights on recruiting sites, and conducting outreach to coaches through networking services like Next College Student Athlete (NCSA). Then, they may enter into direct contact with coaches who are specifically tasked with advocating their recruitment to the school’s admissions committee. Ultimately, however, there is no guarantee that these efforts will come to fruition.

Indeed, according to NCAA data, nearly 520,000 students participated in Division I, II and III sports in the 2022-23 season. This figure also includes walk-on athletes — students who join college athletic programs without prior recruitment — and students recruited from abroad, though these cases are usually far less common. That, compared with the almost eight million high school student-athletes, means only a mere 7% of student-athletes are recruited to play at the collegiate level.

While not all eight million high school student-athletes seek recruitment, those that do face a highly competitive and complex process. Unsurprisingly, then, many also fall short of this goal. Whether these students are denied on the basis of their college application, do not find an ideal match or voluntarily stop their search altogether, each has a nuanced journey and resulting perspective.

Until last semester, senior Marcello Chang had been seeking recruitment. A competitive soccer player since childhood, he — like many of his teammates and school peers — had hoped to be recruited to a top collegiate program. To that end, he followed the basic but strenuous procedure: He sent initial emails directly to programs in his freshman year, attended dozens of showcases and ID camps (showcase-like events organized by specific colleges) during sophomore and junior year, and communicated directly with coaches starting junior year.

Catching the eye of program scouts and coaches is fundamental to recruitment. Chang noted this task is both difficult and financially inequitable.

“ID camps are actually very expensive,” he said. “A lot of the time, players get recruited through these events, and if you don’t have the money for them, you’re less likely to be recruited.”

Senior Ashley Sarkosh, who until recently was actively seeking recruitment for soccer, echoed the importance of player-to-program contact.

“There is a small (and specific) demand for collegiate athletes but a great supply to choose from,” she said. “Anyone can therefore imagine that the required work to get noticed is tremendous, and you have to give it your all.”

According to Zippia, a job-search platform that includes company revenues in its database, NCSA made around $130 million dollars in revenue in 2022. While NCSA services aim to help players with recruitment outreach, they do not include other expenses such as for equipment, training, exercise regimens and showcase attendance. Some of these costs may be covered by athletes’ club teams, but players usually still pay for lodging, transportation and meals. That, combined with the average club membership price — usually in the low thousands, according to the NCSA — means a player may spend thousands of dollars attending showcases throughout high school. These showcases exist for practically all major high school sports.

In addition, the regulations and practices around recruitment can differ among sports, causing additional confusion for and inconvenience to athletes.

“Basically, coaches can’t even talk to (soccer athletes) until the summer after sophomore year, which is not the same case for other sports,” Chang said. “It almost doesn’t make sense to see prodigy football players receive offers while they are still in middle school, or even baseball players who are freshmen in high school.”

Athletes who sought recruitment also draw parallels between the competitive environments around recruitment and the college application cycle.

“Most of the time, you are talking to the same colleges as your teammates,” Chang said. “With college applications, everyone asks, ‘Where are you applying?’ and with recruitment they ask, ‘Oh, which programs are you talking to?’”

Sarkosh noticed similar patterns, fueled by the tendency of both college applicants and recruitment-seekers to maximize their outreach.

“Similar to college applications, athletes know that applying or speaking to one college isn’t enough,” she said. “They must reach out to as wide a variety of colleges as possible.”

Seeking recruitment often necessitates an even greater sacrifice: time. Between playing, recovering and communicating, athletes are often left with less time for academic and social commitments, and limited opportunities to explore other sports.

“Unfortunately, if you are trying to get recruited, you may miss time with friends and family,” Sarkosh said. “Some argue that athletes should explore more high school sports, become more well rounded and therefore save money for college.”

Indeed, what high school students may find on their social media feeds — celebratory recruitment announcements — show merely one fragment of the collegiate recruitment process. For every athlete, no matter the final recruitment destination (or lack thereof), their individual journey consists of great physical, financial and time sacrifices.

“When we see our friends on Instagram posting that they ‘signed’ to a college for a sport, we are happy and excited for them, but we may not realize all that they gave up prior to their signing,” Sarkosh said.