Students, family members, and student-supporting adults should trust that teachers have what’s best for student learning in their minds. Unfortunately, we are instead seen as obstacles for future advancement. This is, of course, different in different communities; but in the community I work in, any pedagogical changes are viewed as “changing the playing field” for the “game” of “doing school”. High school is especially seen as a system that can be “gamed” — if you know the right “play”, you can figure out how to get the “A” without having to put in much effort or admit that maybe there is a bit more to learn.

I have been working in education as a teacher, teacher candidate supervisor, teacher leader, teacher coach, teacher sports coach, and teacher mom for 36 years. When I started in this profession, teachers, administrators, counselors, students, and families were always on the same team – “Team Student”. When a student struggled with academics, with school social situations, or with just being in school, we all worked together as a team to help “student” move forward and grow. There was trust among all team members that we all believed we were doing what was best to support student growth. We were able to have hard conversations, exhibit respect for each other, and come to decisions as a group that helped promote that growth.

In the U.S., teachers have never received the respect accorded to other professionals — doctors, dentists, engineers, etc. Teaching is a profession. We go through training that includes research on developmentally appropriate methods of teaching and learning to help promote growth at all levels. A teacher may have a PhD in their content area, but they still need to return to school to earn their teaching credential before being able to teach in a public school. We are honest in our course catalogs about how much time we think students will need to spend outside of the classroom in order to show proficiency in a specific course. We spend extra time with students to help them when they have questions about our courses as well as things not related to school at all. We do our best to guide students in making good choices. Those of us who have been in education for a long time are able to draw from our experience with former students and families to help current students and families better weigh options when presented with choices about course load and/or work-life balance. Lately, none of that seems to matter.

Recently, (I think starting just before the pandemic) it seems that there are a number of parents/guardians that believe the teachers are getting in the way of future goals.

“If my student can’t get an A, they won’t be able to…”

“Your system of grading is preventing my student from learning.”

“I want my student to have a different teacher because my student said the teacher…. No, I haven’t spoken with the teacher about it to clarify…”

“You can do anything but not everything” — David Allen

We highly encourage students and families to be thoughtful in their course selection at the start of the second semester for the following school year. We recommend taking no more than 2, maybe 3, advanced placement (AP) courses because of the time commitment needed to take a college-level course, and the resulting effect overcommitting can have on quality of life (both for students and their families). When students (and their parents/guardians) insist on enrolling in 5+ AP courses, we warn them that this will be a heavy load. (People rarely take 5 courses per term in college, why would someone take 5 college-level courses in high school?) The following school year, when the student is enrolled in those courses and starts to become overwhelmed, it isn’t the choice of taking the heavy load that is blamed for their stress — rather, the teacher is blamed for “not being flexible”, or “the grading system stresses my student out and doesn’t allow them to succeed,” or “the pace of the course is too fast and is impossible to keep up with.” If the tail of the last sentence was, “…along with my 4+ other AP courses,” then there could be a conversation about load and quality of life; instead, blame is incorrectly placed on the teacher for causing anxiety and stress in their particular course.

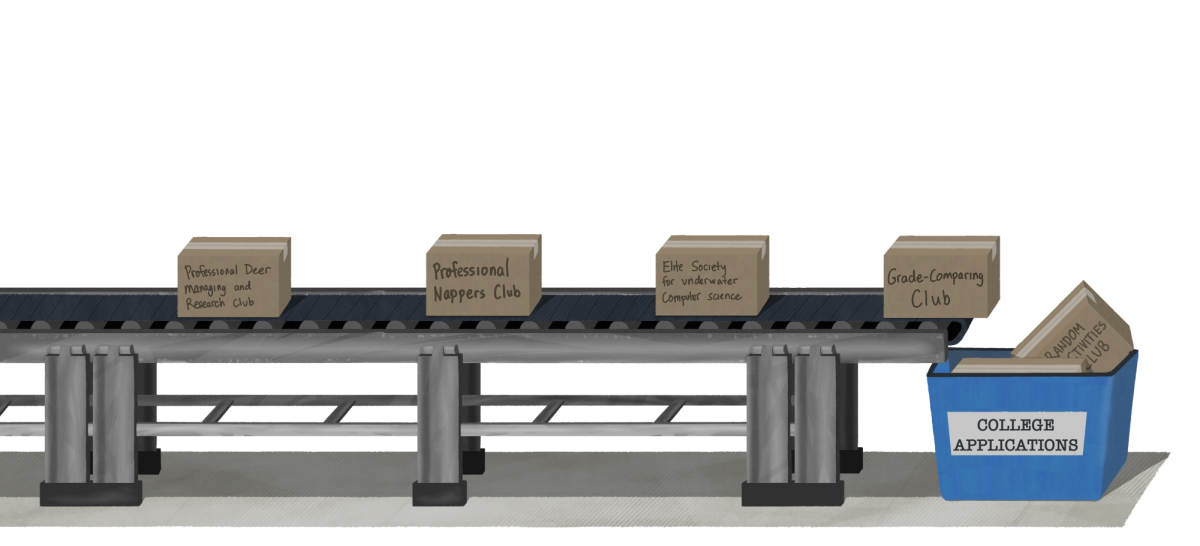

I know that our counseling department tries very hard to talk about course choice and lightening the load. The counselors are often met with families who think that keeping a balanced course load will lessen the chances of their student “getting into a good college.” At the same time, some families also feel that their student needs to be getting an A in each of those classes in order to get into that “good” college. This way of thinking creates undue pressure on the students from themselves and their families. No wonder there is anxiety and stress.

In the end, our charge as high school educators is to prepare our students for what comes next — more learning. That might be learning in college. That also might include learning to be a responsible adult/citizen. “Doing School” may allow a student to get into a certain college, but will they then be successful there? Here is a comparison of what teachers want for students and what we see many students actually doing:

![]()

That brings me to Evidence-Based Teaching and Learning (EBTL). As I have previously stated, I have been in education for 36+ years. I have seen many systems of assessment. When I learned about EBTL more than 8 years ago, I thought, “Finally! A system which allows student grades to be based on what they know, not just whether they know how to ‘do school’ well.” A system that allows for growth in learning without penalizing some students for understanding things at different rates than others. A system that has been around for 20+ years, and has been designated as “new” by my district. Yet with all this, a system that is being blamed for students getting low “grades” when they’ve never had low grades before.

In some of our advanced placement science courses, we are assessing the students on the science practices that will be assessed by the College Board. We believe this will give students a better chance to show their understanding of course-specific practices and skills and prepare them to take the AP exam. We have seen in our college prep courses that when you assess content through the lens of practices and skills, students are able to show growth even when the content understanding is not perfect. Students demonstrate their growth in learning throughout the school year. We do not expect these demonstrations of learning to be “perfect” when beginning to apply the skills in the context of the content. This means that if students have trouble applying the practice at the start of the year and, say, do poorly on their first assessment, then they still have an opportunity for recovery without constantly having to retake an assessment. The expectation is that students would then analyze their mistakes, look at how they are practicing and studying, make adjustments, then show growth in learning how they learn, thus becoming independent learners. Our teaching team has worked very hard to be thoughtful in our implementation of EBTL. We believe in what we are doing and we feel that students who stick it out will also see the benefits.

Sticking it out…

Resiliency builds character. For some reason, sticking something out also seems to be going by the wayside. I always cheer for my students when they are super confident in an answer they volunteer to say out loud and turn out to be wrong. “Awesome!” I say, “You have now grown even more brain cells. Getting something wrong leads to learning!” Students don’t like to be wrong. When I have given feedback on certain types of prompts and a student says I’m “being picky,” I point out the misconception that is demonstrated by their mistake and let them know that they have a bit more learning to do. Struggle is necessary for us to learn. Getting something wrong and then working out how to get it right helps the learning stick in our brains. A colleague said that they say this in our Living Skills class, “Being happy isn’t about the absence of adversity, it’s about how you deal with that adversity and get past it that determines your personal satisfaction.” Somehow, though, our community has forgotten these things. Instead of “when the going gets tough, the tough get going,” we observe that “when the going gets tough, drop the class.” Or, “if you aren’t constantly earning the grade you “need”, drop the class.” The students I have taught that have stuck with me through the struggle and persevered, have always developed a sense of personal pride and confidence that they didn’t have before. Those that drop still think they aren’t good at this kind of course.

Experiencing adversity is unavoidable in our society. Keeping our students away from experiencing adversity keeps them from understanding how to overcome it. Our job as educators is not to dole out adverse situations, but to provide our students with the tools they need to learn and grow. Learning is different for different people — different paces, different topics, different skills. Some students will experience roadblocks when others do not. Teachers support all learners at their current levels, and encourage them to own their learning process and grow. I want for teachers to be trusted for the professionals we are. I hope we can be recognized as being on “Team Student” again. I hope it happens tomorrow.

Laurie Addleman Pennington is a science teacher at Henry. M. Gunn High School. She has been in PAUSD since 1993.