Written by Shagun Khare and Grace Ding

When sophomore Jojo Qi began dancing in elementary school, it was a form of art. The stage was her canvas and she was the paintbrush, decorating the blank slate with intricate pivots and vibrant pirouettes. But as the paintings on her stage developed through middle school and eventually high school, Qi began to dislike what she saw. Sure, her movements looked fine. But did she look fine?

At around age 13, Qi, like many young ballerinas, began to strive for the “perfect dancer’s body,” but through unhealthy means. She started restricting her diet and consciously calorie-counted to ensure that she could maintain the ideal ballerina physique. “When you see dancers that are professional, they have got legs that go on for days and arms that are like sticks and you’re like, ‘I don’t look like that; should I look like that?’” Qi said.

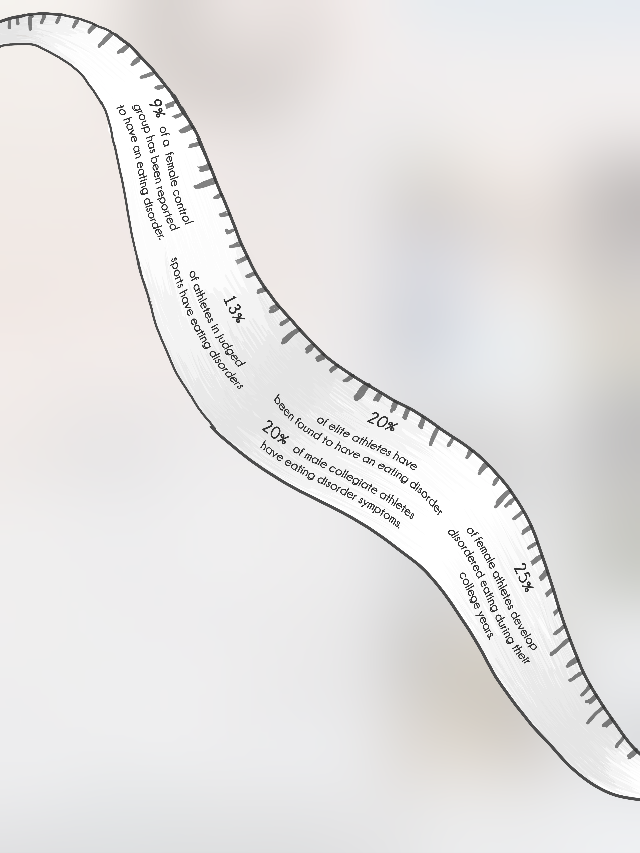

According to the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), Qi’s case is not an isolated incident. Dancers are 10 times more likely to get an eating disorder than their non-dancing peers. But why is that so? In sports across the athletic spectrum—whether it be dancing, wrestling, gymnastics, running or figure skating—a certain body type is often expected or prevalent among a sport’s athletes. At times, these sports can allow athletes to feel more comfortable with their bodies, but for others like Qi, the aesthetic expectations of a sport can cause an athlete to create an unhealthy perception of how they should treat and regard their body.

The Catalyst

Most athletes’ body image issues are sparked through insecurities that are present even before the athlete first joins the sport. According to sports psychologist Michelle Cleere, low self-esteem and feelings of lacking control manifest at early ages and eventually translate into the more physical forms of self-harm that athletes exhibit later in life. These cases, however, are most prevalent in judged sports that have an aesthetic or performance value attached to the required athleticism, such as dance, cheer and gymnastics, in which the way an athlete trains and how they are expected to look are often at odds with each other.

The pressure does not solely come from the judging aspect; it also stems from a desire to fit in to the perfect, one-size-fits-all mold often portrayed in surrounding athletes’ physiques. In dancing, for instance, the preferred body type depicted in media and often manifested in studios is lithe and thin. According to ballet dancer sophomore Kim Li, this stimulates unhealthy behaviors in young athletes. “Most dancers are built like everyone else, but when we see professional dancers, we compare them to ourselves,” Li said. “To get that body type, many dancers try stretching more often and sitting in oversplits, but I also know of a few dancers who starved themselves to thin out their body.”

In wrestling, the pressure to maintain an exact weight to fit into certain weight classes can bear heavy on athletes as well. “[There have been cases where] making the weight became more important than winning, and athletes would eat too little, have no energy or have a messed up perception of themselves,” wrestling coach Chris Horpel said. Varsity wrestler junior Andrew Maltz noted that wrestlers may have to go to extremes to ensure they can compete within their weight class. “Multiple wrestlers this year have had to lose seven to eight pounds in a matter of a few days to make weight for a competition,” Maltz said. “Some have to sweat out five pounds of water in a single practice, while others have to reduce their food and water intake to almost zero.”

The Negatives

As general body image and dysmorphia begin to take over athletes’ lives, essential and even mundane tasks become difficult to complete. Athletes can become so engrossed in their relationship with food, body image or training that their relationships with friends and family begin to wither. “It’s harder for people to be social because they sort of want to hide,” Cleere said. “They usually spend a lot of time thinking about food and a lot of time training, so they don’t always have a lot of time for social life.”

Qi’s eating disorder resulted in drastic fluctuations of how she perceived her body and her dysmorphia would occupy her mind to the point where it was hard to concentrate on much else. “I started getting really focused on the nitpicky details, which made me really stressed, and when you’re stressed you tend to eat more. Then I thought I looked bloated and I needed to eat less again,” Qi said. “And that just really spirals downward because you see your body [gaining weight] but in your mind you think, ‘I only ate blank calories; I shouldn’t look like this.’”

According to Cleere, this increase in stress and attention to detail can also cause a person’s athletic performance to debilitate. Athletes with body image issues will often end up feeling fatigued, as they do not receive a proper nutritional balance and cannot sleep at night as a result of anxiety or other side effects. Depending on the severity of an athlete’s disease, the brain and physicality of an athlete could be affected as well. “Anorexics are starving themselves, which also means they’re starving their brains, so they can’t think well a lot of times,” Cleere said. “They don’t have a lot of endurance, their bones get frail and a high number of injuries tend to come along with people with eating disorders as well.”

So, with all these adverse effects on an athlete’s performance, why would athletes put themselves through so much just to look a certain way? According to Cleere, athletes do not necessarily attribute their poor performance to their eating disorder, seeing their appearance and athleticism as two separate entities.

For instance, when Qi began losing weight, compliments about her figure would further her desire to become thinner, regardless of how she felt when she was performing on stage. “Family friends started noticing and the parents would be like, ‘Oh you have such a nice figure now; I can see you lost weight,’” she said. “That just made me want to restrict my diet even more because if they were saying positive things, then you think this is obviously the right thing to do.”

The Positives

While for some athletes, sports have exacerbated body image complications, for others such as Maltz, sports have allowed athletes to appreciate their body type and use it as an athletic prowess against opponents. “Before wrestling, I was always the slow, overweight friend and I really didn’t have a lot of close friends to hang out with,” Maltz said. “Wrestling taught me to not only look past my body issues, but to embrace them. I finally found a sport where I could use my weight and size to my advantage, and where I could be successful even though I was not the most athletic.” Since his freshman year, Maltz has gone on to win multiple Central Coast Section titles and competed at the state level for wrestling.

Horpel attributes the wide-range of success among wrestlers of various body types to the very nature of wrestling: athletes prioritize what helps to win and not what helps them look the best if they can overcome their body image issues. “The beauty of wrestling lies in that it doesn’t really matter what body type you are as long as you use technique tailored to it,” he said. “Wrestling is a sport where luckily, training is what makes you have the body type you want.”

According to Maltz, when a wrestler looks more heavily built than the other, it can cause a sort of “intimidation factor.” But sometimes, Maltz says, looks can be deceiving because the wrestler is ultimately judged on his or her ability to knock down the opponent. “If the smaller wrestler has more skill, then he’s got just as good a chance of winning as the bigger wrestler, and that reduces the pressure to look a certain way,” he said.

Recovery and Hope

Despite increased awareness of eating disorders and dysmorphia in sports, there is still a prevalent but detrimental stigma that questions athletes who have eating disorders and their intentions. For bystanders, the idea of an athlete damaging their own health is hard to comprehend. However, to transform from a bystander into a confidante for athletes with body image issues, Qi recommends that students support their friends in ways that do not solely revolve around their looks. “Tell [your peers] something else about their personality and not just their physical appearance,” Qi said.

Once an athlete forms a support system, athletes should receive an official diagnosis. From there, medication, therapy and other forms of recovery can transpire. For athletes who are struggling to cope with their body image, Maltz believes a change in mindset is imperative to begin a process toward recovery. “I’ve been down the same path that they are going down, and I know that in the end, looks won’t determine your performance as an athlete,” Maltz said. “If you can learn to use what you have to the best of your ability, you might surprise yourself [with] what you can do.”

Both Maltz and Qi agree that eventually, it is the transition from self-hate to self-love that is most impactful in an athlete’s recovery. “You are the most important part of the process,” Qi said. “So just love yourself for who you are right now and find other things that make you happy besides the way you look.”