Written by Jenna Marvet

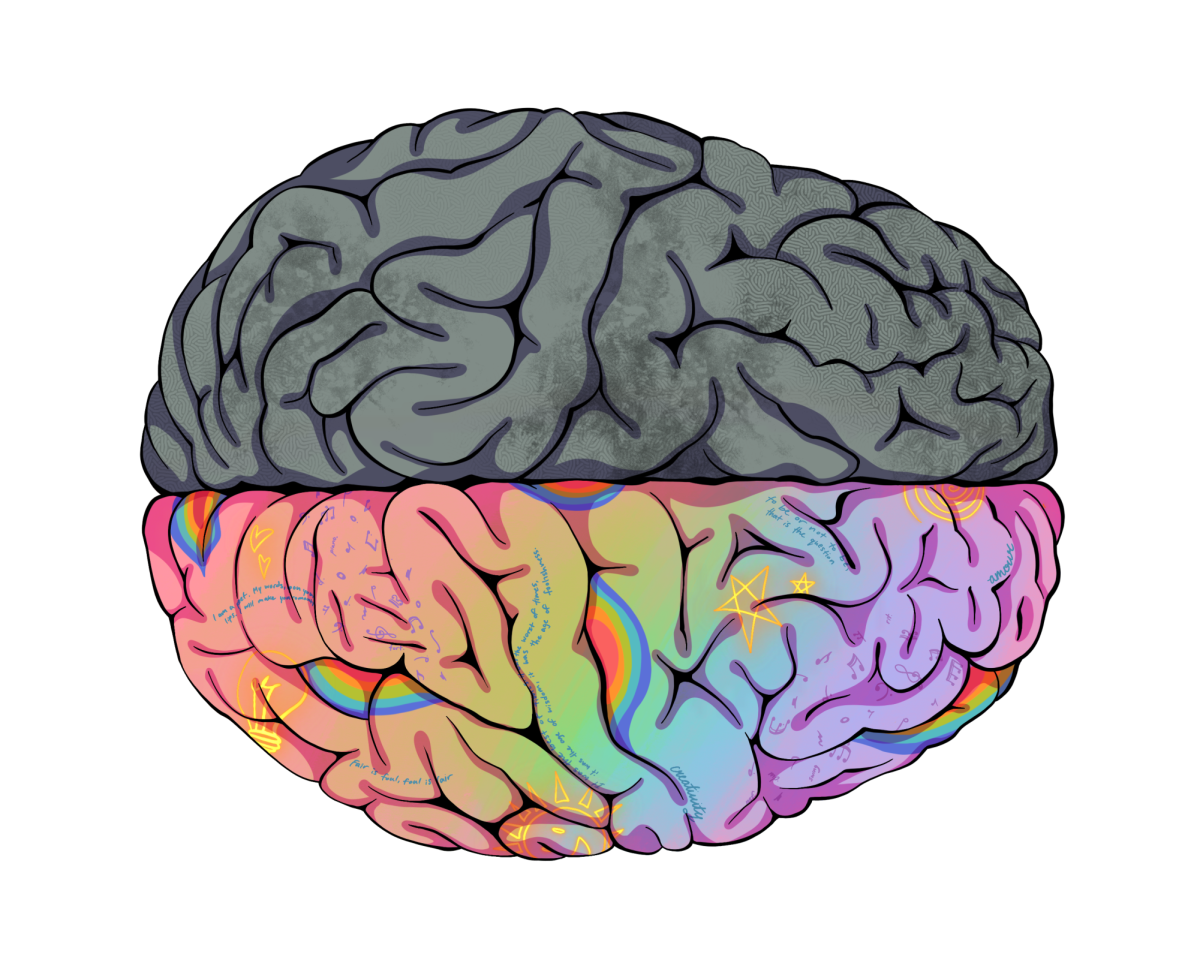

Making computer science a graduation requirement would be detrimental to the already undervalued, humanities-focused students and limit the flexibility high school students have to explore career options before college.

According to Forbes, the Bay Area is the number one place to find tech job opportunities so many professionals are involved in the tech industry. In reality, there are a plethora of careers that do not require coding and computer mechanics. Still, Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) careers are the most visible and celebrated in Silicon Valley, even in the name of the region itself. Thus, it is understandable why local teachers are discussing making computer science a high school graduation requirement. The notion is tacked on to a distorted community belief that success in STEM is paramount, highlighted by Gunn students and alumni in the “Atlantic,” “Vice” and “San Francisco Gate” articles covering Gunn. As a result, many students feel the need to participate in many rigorous STEM courses; Gunn was ranked number five U.S. News Best STEM High Schools in 2014. The school offers eight different AP STEM classes, more than two times the social studies and English AP classes offered. Students at Gunn who want to challenge themselves by taking college level humanities courses have limited chances. By making computer science a graduation requirement, these students will be further limited in their ability to invest time in more difficult classes that relate directly to their strengths and career path.

While teachers contemplate an additional science requirement, they are ignoring the fact that many students have lost humanities-related skills. In a 2013 NBC article entitled “Why Johnny can’t write,” employers said that job candidates lacking in writing and communication skills were unlikely to be hired. The article attributed this influx of less qualified candidates to a national focus on STEM in high schools that began during the Cold War. Top university STEM professors received extra funding while English and other humanities were left in STEM courses’ dust. We can still see the effects of this today: according to “The National Report Card” published by the United States Department of Education in 2012, only 27 percent of twelfth graders were proficient in writing. Humanities classes teach these integral skills that students are lacking, but they are often ignored for not being as important as STEM classes, especially in Silicon Valley.

It is true that computers are important in a variety of jobs and in daily life, but that does not mean that all students need to learn computer science. The basic computer skills—such as knowledge of programs like Excel and Powerpoint—that are integral in our daily lives and future careers should be a graduation requirement instead. These skills should be added to required curricula in Living Skills, which is already a graduation requirement for students. By doing this, it would not limit students’ abilities to explore other career education and electives classes that would be hindered by adding yet another graduation requirement to complete by the end of senior year.

Although some students may choose to pursue a computer science education, it should not be made a graduation requirement. Gunn needs to reevaluate the weight of importance it puts on STEM studies over humanities, to make sure that all students can be enriched in their studies, explore career options and learn the skills pertinent to being a competent adult.