Reading between the lines: Nuances in language alter our perception of everyday life, with meaningful consequences

“You guys!”

Almost everyone—male-identifying or not—has been called “a guy” at least once in their life, whether it’s through the welcoming words of a teacher, an enthusiastic text or an obnoxious shout across the hall. To most, this word is just that: a common greeting.

It’s become so commonplace that many don’t even consider the genders of the people they’re referring to, and if they do, they find no issues with it. Others, however, disagree, citing the significant discomfort and exclusion it causes; for some, being frequently misgendered is nothing short of erasure.

Language undeniably impacts every aspect of our lives, even if we barely think about it that way. Without it, we wouldn’t be able to tell our parents that we love them (or gossip fruitfully with friends); we wouldn’t be able to complain endlessly about homework or make blunt jokes about others. While language is often used in the same way—to communicate—the manner of getting the message across varies at an immeasurable level.

The smallest differences in language can contribute to a variety of perspectives and meanings, many of which can be harmful or outright incorrect.

It may seem trivial to focus on seemingly superficial colloquial phrasing and ancient gendered language systems; however, at the very least, it’s important to consider how much it impacts others. At its core, even the smallest differences in language can contribute to a variety of perspectives and meanings, many of which can be harmful or outright incorrect.

AAVE

The most profound—and possibly the most well-known—impact of language differences is made clear in African American Vernacular English (AAVE), a dialect commonly used by Black Americans that has recently been the subject of numerous cultural appropriation debates. With its distinct sentence structure and dropped consonants, AAVE has been around since the 17th century, stemming from Africans that were brought over from Africa, the Caribbean and South America, according to Stanford Linguistics Professor John Rickford. The dialect was formed in an environment of oppression—one with many speakers and very few teachers.

AAVE is often seen as “lazy” and “unprofessional,” making it harder for speakers to earn the credibility that they deserve

Rickford noted that, to African Americans, AAVE is a more informal, conversational dialect they may use when speaking to others in the same community. Non-African Americans, however, view AAVE differently. “People tend to think AAVE is careless and unstructured,” Rickford said. “But it’s just like any other language in that it has rules. You can’t just make things up.”

This faulty perception is undoubtedly harmful for AAVE speakers. According to Rickford, AAVE is often seen as “lazy” and “unprofessional,” making it harder for speakers to earn the credibility that they deserve. In his explanation, Rickford cited the trial of George Zimmerman for the murder of Black American Trayvon Martin in 2012, when Rachel Jeantel, the leading prosecution witness, gave her testimony in AAVE. The jurors dismissed her vital testimony and acquitted Zimmerman, likely because they could not “hear, understand, or believe her,” Rickford and linguist Sharese King wrote in a paper.

Naima Small, founder of the Instagram platform “Dear Dark Skinned Girls,” expressed a similar sentiment and argued that this skewed perception limits opportunities for AAVE speakers. “I think it harms the Black community largest because [of] that idea [that] you speak AAVE equals you can’t possibly be educated [or] have anything to say,” Small said.

Most recently, social media apps such as Twitter and TikTok have pushed many AAVE terms like “chile,” “finna” and “periodt,” as well as AAVE’s unique sentence structure, into the spotlight. These terms are now being used by everyone—not just African Americans. For instance, Asian American actress Nora Lum, more commonly known as Awkwafina, is notorious for having a “persona [that] has veered too close to black aesthetics for comfort,” according to Vulture Magazine.

Rickford, on his end, doesn’t find this adoption very problematic, yet noted that some AAVE speakers do. “[These speakers say,] ‘They are taking our language without paying their dues,’” he said.

Small echoed Rickford’s general indifference to the widespread use of AAVE terms, but added that it’s important for all users to understand the origins of these terms. What frustrates Small the most about the adoption, however, is that these terms are viewed as a “trend” instead of a lasting part of the dialect. “What really gets me mad [is] that people are like, ‘Who still says chile?’” she said. “Like, [chile] wasn’t just some kind of trend.”

Gendered Nouns

Of course, it’s not just dialects that can shift meaning—entire languages can be constructed around gender and perpetrate sexism. In most romance languages—French, Spanish and Portuguese, to name a few—nouns are assigned a gender and are preceded by one of the two definite articles: the feminine or the masculine. Usually, the gendering of nouns isn’t problematic; very few complaints have been raised about the femininity of a cup, for instance. When it comes to professions or descriptions, however, the negative effects of this foundation become clear. In languages such as Spanish and Portuguese, there are multiple options used to refer to an occupation. But when referring to groups of people—or someone whose gender is unknown—the masculine form becomes the norm. For example, a group of actors and actresses is “los actores” in Spanish, even though an actress is “la actriz.” “If there’s a convention of picking the masculine form as default, then you’re reinforcing a notion that the normative person in this profession is male, and you only go out of yourway to say, ‘Oh, this is a female author or a female teacher or a female doctor’ when that’s true,” University of Washington Computational Linguistics Professor Emily Bender said.

This clear lack of lingual representation may perpetuate harmful stereotypes about the gender compositions of professions that are outright false or discourage women, who frequently hear these masculine forms being used, from pursuing certain careers. “[Women] can feel sort of out of place,” Bender said.

Furthermore, romance languages have recently faced extensive criticism due to their lack of non-binary pronouns. The Spanish language, for example, contains only two pronouns: el, the masculine, and ella, the feminine. This system only functions if there are only two genders; these pronouns don’t describe non-binary or genderqueer people, or people whose genders lie outside the gender binary, according to Stanford Youth Development Manager Ana Lilia Soto, who works in the mental health field. “It can be super problematic for young people who might not identify [with the gender binary] or are more fluid with how they describe themselves, and it can be off-putting,” she said. “It’s kind of like asking somebody, ‘Well, where’s my community if I don’t identify with this or with that?” To adapt, many Hispanics have adopted the pronoun “elle,” or the plural “elles,” as a gender neutral option.

Similarly, for people of Latin American descent, the all-inclusive term “Latinx” was coined to replace “Latino” and “Latina.” Yet according to Pew Research, even though one in four Latin Americans have heard of the term, only 3% use it. World Language Instructional Leader Liz Matchett, who teaches Spanish, noted that making changes in favor of inclusivity will always be difficult—no matter what, not everyone will agree. “There [are people] that say, ‘Don’t do it because the people in charge of language say that you just need to do this, and language doesn’t make any kind of political or gender judgment statements,’” she said. “It’s just saying that this is [how it is]. And then there’s the people who say, ‘Don’t even tell me how to do this because you aren’t even part of my culture. I don’t want to be told by anyone what the right way is.’”

English teacher Diane Ichikawa brought up another concern that comes with adapting these languages: fluidity. “It’s a necessity to take care of everybody who’s in our community and in our society,” she said. “And at the same time, linguistically, [a] roadblock to that is that [it’s not] fluid to say ‘Latinx’ like that. How do you even say that in some languages, right?” In response to the somewhat confusing pronunciation of “Latinx,” some Spanish speakers have adopted “Latine” as a more fluid alternative.

To address these recent debates over the romance languages, Gunn’s Languages department has encouraged teachers to be more gender-neutral. According to Matchett, a steering committee is currently developing a plan to bring to the district in hopes of establishing more inclusive practices in the language departments. “I haven’t ever done anything formalized with my department, but I have said in passing to teachers and especially teachers who may have non-gendered students in their classes or transgender students [to] find a way to be inclusive,” Matchett said. “I don’t care what it is, I don’t care what you follow, but make sure you find a way to be inclusive.”

Matchett acknowledges, however, that there isn’t one correct way to address the issue of inclusivity. “I’m not going to advocate for one way to do it because there isn’t an agreement in the language world about the right way to do it,” she said.

Colloquial Terms

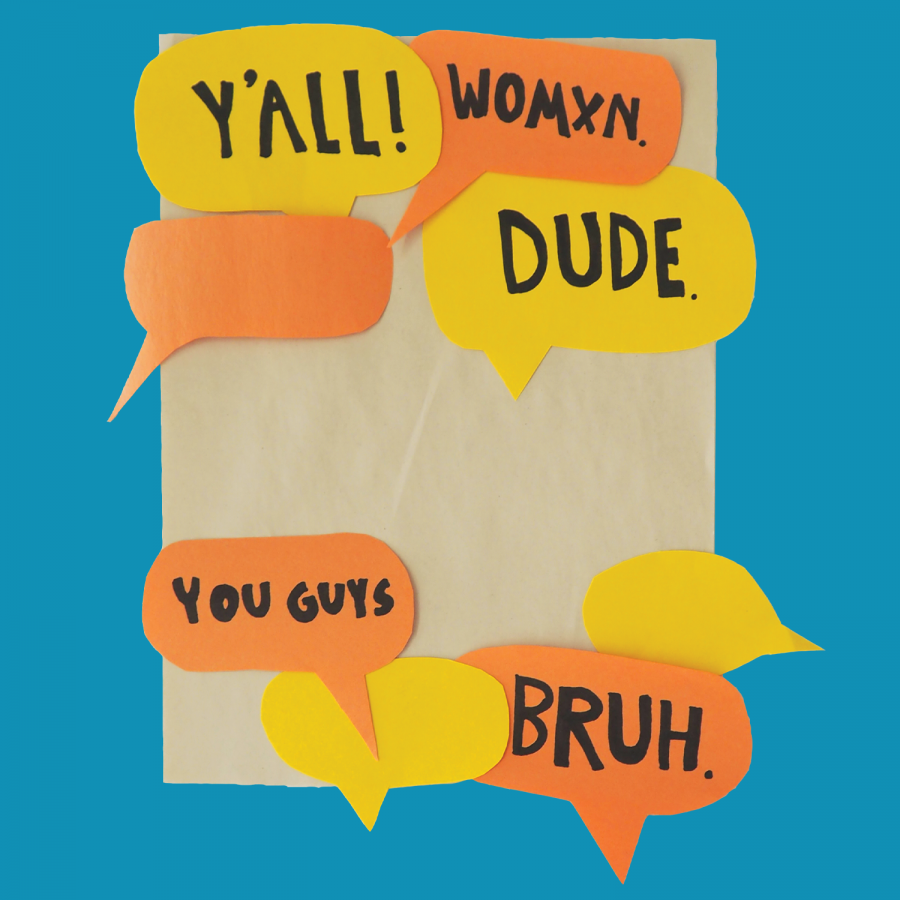

Gendered language also rears its head in colloquial terms such as “you guys” and “dude.” Though frequently used to refer to people of all genders, both of these terms have masculine roots. “The singular word guy is definitely masculine,” Bender said. “If you say, ‘I met a guy the other day,’ most English speakers are going to imagine a male-presenting person.” Using these terms to refer to non-male individuals may lead to discomfort and exclusion, among other things. In a video for Makers.com, author and activist Alice Walker argued that the continued use of these masculine terms, especially by women themselves, is only due to a “fear of feminism” or a desire to ignore any sentiments of feminism. Others raised concerns that these terms may only exacerbate any underlying sexism from earlier centuries. For transgender people specifically, these masculine terms may misgender them, serving as an unwelcome reminder of a past they’re looking to forget.

These terms are so strongly embedded into our everyday language that it makes any awareness of their impacts—and tangible change—rather difficult.

Ichikawa noted, however, that these terms aren’t problematic to everyone. “You can make a lot of arguments that it’s fine [and that] we need to be okay with that and not so thin-skinned,” she said.

These terms are so strongly embedded into our everyday language that it makes any awareness of their impacts—and tangible change—rather difficult. “Our language has become so colloquial that we don’t really think about it,” Ichikawa said. Still, many people are looking for change and have adopted gender-neutral terms such as “folks” and “y’all.”

Gunn, meanwhile, is trying to make inclusive practices the norm. On March 21, the Student Executive Council, along with Adolescent Counseling Services and Outlet, hosted a Pride Week Livestream where they provided a list of more inclusive alternative words to refer to relatives and friends. The list included terms such as “partner” in place of “husband” or “wife,” “folks” and “everyone” in place of “you guys,” and “sibling” in place of “brother” or “sister.”

Mental Health

Language’s impacts, of course, don’t stop there; mental health—something Gunn has been striving to address—is widely affected, particularly in regards to terminology surrounding suicide. In colloquial language, mental health presentations and informational articles, we often refer to someone “committing suicide,” a phrase Soto and countless others have pushed back on. “When we think of ‘commit suicide,’ there’s this criminal act that happens, like people commit murder [and] people commit burglaries,” Soto said. “It’s a criminal thing.”

Instead, medical and mental health professionals have shifted towards using “died by suicide” whenever possible—a change that emphasizes that suicide is a public health issue and a change that, according to Soto, others should follow. “I think it’s really about acknowledging that this person died by suicide because of things that they were going through and [that] this is an action that was taken,” Soto said.

This language, Soto added, helps make dialogue about suicide and other mental health issues much less ambiguous.

Soto also notes that referring to suicide attempts as “successful” or “unsuccessful” has been problematic. These terms, according to the Mental Health Center of Denver, imply that suicide is something to be accomplished. “Is there a really ‘congratulatory’ [or] a ‘successful’ suicide?” Soto said.

Instead, people should opt for using more direct language like “suicide attempt” in place of “unsuccessful attempt” and “died by suicide” in place of “successful attempt.” This language, Soto added, helps make dialogue about suicide and other mental health issues much less ambiguous. “I think the more direct that we can be with getting people who do have suicidal ideation [to engage] in their own decision making, as well as [demystifying] that to the general public, I think it’s helpful,” she said.

From the exclusion fostered by starkly gendered romance languages to faulty, damaging misconceptions of AAVE, language’s deeper implications—although sometimes difficult to recognize—assert themselves in meaningful ways.

Thankfully, some progress is being made. Linguists are adopting new words and phrases to minimize the exclusionary effects gendered language has, and are increasing general awareness of language’s effects through numerous articles and social movements.

Gunn’s teachers, in particular, have attempted to make the classroom more welcoming by altering their language. “As a teacher, I will accept you for whatever you decide to use as your pronouns and the way to speak about it, and I’m not going to force you to choose a pronoun that doesn’t feel right to you,” Matchett said.

Despite these recent efforts to make language more inclusive and direct, there is still more work to be done. “It is [clear] that a lot of our social world is constructed through language,” Bender said. “So in that sense, [the] categories we experience and the way we understand that people in relationships around us is very much influenced by not only what we name and how we talk about things, but also [language] variation.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Henry M. Gunn High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Since joining staff in Jan. 2020, Julianna Chang has been editing pages and advising staffers as a Managing Editor. In addition to devoting every spare...

Senior Mia Knezevic has been on staff since Jan. 2020, and currently holds the positions of Forum and Photos Editor. When she isn't writing stories or...