Athletes weigh in on body image issues

Before every high school track and field meet, class of 2022 alumna Sharona Schwab meticulously planned out her dieting regimen: she would load up on meat and protein for four days, switch to whole grains and carbohydrates two days before competing and eat a mix of protein and carbohydrates on the morning of. Schwab’s careful scrutiny over her diet reflects the wider pressure on athletes to maintain certain weight classes, eating habits and body types for the sake of their sport. While often originating from an innocuous desire to reach one’s full athletic potential, this pressure can carry serious ramifications. According to a 2018 study published in the Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 7.3% of high school athletes struggle with an eating disorder—over three times the rate of high school non-athletes. The intense focus on constant improvement, comments from coaches and teammates as well as societal expectations regarding gender and body image can all shape an athlete’s perception of their body and negatively impact their self-confidence.

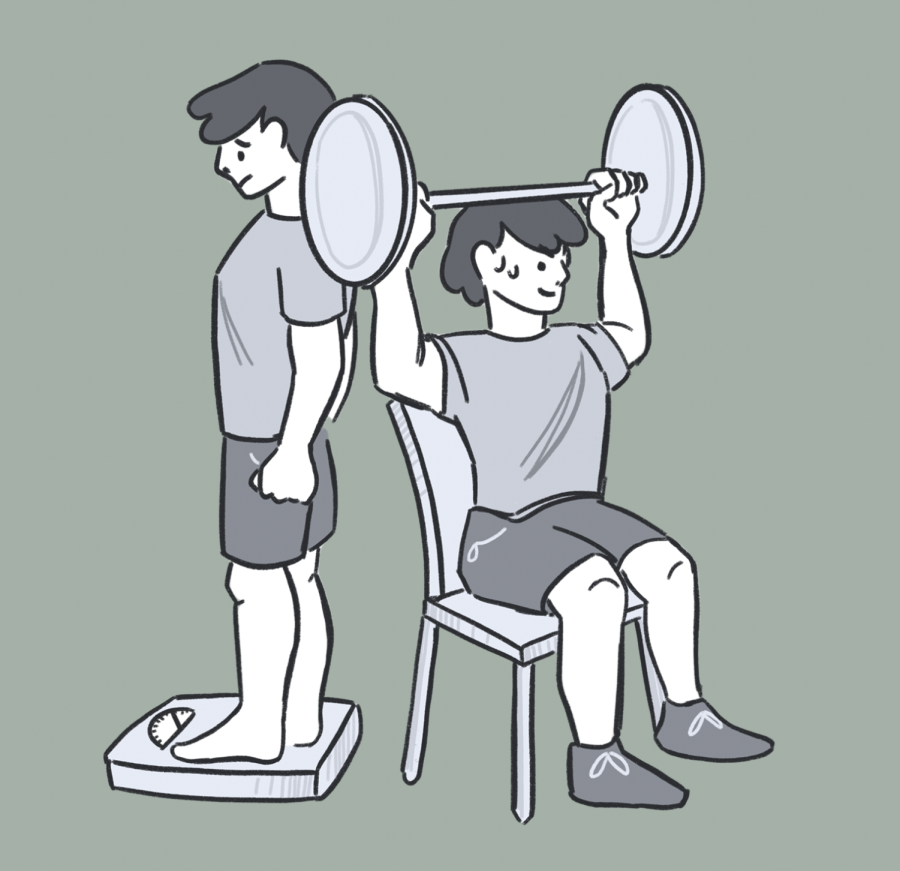

One normalized aspect of athletic culture is openly discussing methods to gain or lose weight. The “ideal weight” for athletes depends on which sport they play: power-dependent sports such as softball and wrestling often favor more heavyset athletes, while speed- or performance-focused sports like sprinting and cheer idealize thinner body types.

Softball player junior Aarushi Kumar has experienced pressure to achieve an “ideal weight” from a young age. “Softball is a power sport. You need a lot of power to play properly, so people seem a lot more comfortable putting pressure on you to change your weight,” she said. “I’ve always been on the underweight side, which, genetically and biologically, is totally normal. But in softball, when you hit 10 years old, your coaches feel like it’s okay to start putting this type of pressure on you. When people keep emphasizing that you look some way, it messes with your brain a little bit, especially at that age.”

Cheerleader freshman Meagan Sutherland emphasized the unique expectations surrounding weight in cheer and dance. “If you’re performing, people are watching you, and there’s definitely pressure to look a certain way or fit a certain way into your uniform,” she said. “In cheer, there is also lots of pressure for flyers to stay thin and maintain a light body in order to be lifted into the air, or they could be switched to bases, which can be very damaging to someone’s self-esteem.”

In wrestling, athletes are often encouraged to lose a specific amount of water weight in order to “make weight,” or fit into a certain weight class. Wrestler junior Mihlaan Selvaretnam has witnessed the consequences of the culture on athletes. “It’s become part of the culture to cut weight and lose weight,” he said. “And it’s not necessarily a good thing. But since everybody does it, you kind of have to.” To make weight, depending on the amount of weight he plans to lose, Selvaretnam will typically keep meals light a week before competing and cut out nearly all water the day before.

While care for one’s eating habits is important and even beneficial under the right circumstances, Schwab’s intense focus on her pre-competition dieting routine negatively affected her relationship with food, even in the track off-season. “Because I had built in that emphasis on eating habits and food, I found myself caring too much and thinking too much every time I was eating, even if I wasn’t competing,” she said. “When I’m paying attention to everything I put in my body and making sure I have enough protein every single meal, it can get really stressful and tedious at times. It takes away from the enjoyment of eating.”

Much of the pressure to diet, work out or look a particular way comes not only from an athletic context but a social one. Sutherland recalled an incident that occurred when she was in the locker room before practice. “I have a strong memory of my friends going through every single one of the girls and talking about how their skirt fits them,” she said. “Like, ‘Oh, I wish my skirt would fit like that. Oh, hers is so much longer. She’s really skinny. She has a big butt.’ Everyone was comparing themselves to every single other person in that room.”

Water polo player junior Ron Zamir argues that select social influence can be beneficial in motivating people to stay healthy. “I feel like working out to impress someone is a dangerous mindset to have,” he said. “A lot of it comes from social media now, especially because there are a lot of people in the gym with TikTok going around. But staying healthy and working out is a good thing. As long as you stay educated on what you’re doing and you’re not blindly following what you see on social media, it can be important. It’s good to remember to not only do it for other people and to have a goal for yourself.”

One of the largest factors behind an athlete’s perception of their body is not related to their physicality at all but rather to their gender. Badminton player junior Troy Woodley, who is nonbinary, described their internal conflict between appreciating their body’s ability while disliking its appearance. “I present very masculine, and I don’t really like that,” they said. “So on one hand, I’m not super happy with my body, and I don’t know exactly how I want to look. But on the other hand, I’m able to perform well in sports, and I don’t want to lose that.”

Schwab also noticed the preference for more masculine bodies in athletics. “Especially as a female athlete, it’s harder to figure out what people even want to see in an athlete aesthetically,” she said. “I feel like on the men’s side, there’s always a specific goal of looking very muscular, which isn’t necessarily the ideal for female athletes. Sometimes I’ve been unsure if I even want to look super strong, and I’m self-conscious about bulking up a lot. It’s not necessarily a trait that is praised like it is for male athletes.”

An athlete’s race or ethnicity also contributes to how they feel about their body while playing a sport. “I play a sport that is predominantly white,” Kumar, who is South Asian, said. “There are a lot of comments about skin color, especially when you’re in the sun a lot. You hear a lot of comments like, ‘Oh, I don’t want to tan too much.’ When I tell them it’ll be okay if they wear sunscreen, they say, ‘No, it’s more of an aesthetic thing.’”

To feel more secure in their own bodies, many athletes aim to avoid social pressure, focus on performance over appearance and keep their sport in perspective.

Sutherland works to steer clear of harmful content both online and in person. “The biggest step I’ve taken to feel more confident in myself is ignoring people’s comments,” she said. “If I’m scrolling through social media and see a video about body image, tips to be thinner or how to lose weight quickly, I just scroll past it to block out anything that might make me feel insecure.”

Selvaretnam prefers to hone in on the physical advantages his body provides rather than how well it fits into a standard body type. “I’m a bit on the taller and skinnier side,” he said. “I’m not very short or stocky like the usual wrestling body type is. In the beginning, it was tougher for me to address, but once I realized that I can use my height to my advantage, it wasn’t as big of an issue for me anymore.”

Schwab reminds herself that her sport is only one part of her life. “It’s important to focus on track some of the time, but remember that I’m doing this for fun,” she said. “I’ve gotten better over the years at going with the flow and not worrying about the effects of my diet on my training because at some point, you just have to live your life. The sport isn’t everything. Separating athletics from the rest of your life allows you to keep enjoying things like eating without the sport taking over your mentality.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of Henry M. Gunn High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

On staff since January 2021, junior Carly Liao is a Forum editor for The Oracle. Outside of the newspaper, she enjoys running, doing crossword puzzles...