The weight of gym culture: Student gym-goers experience ugly side of exercise

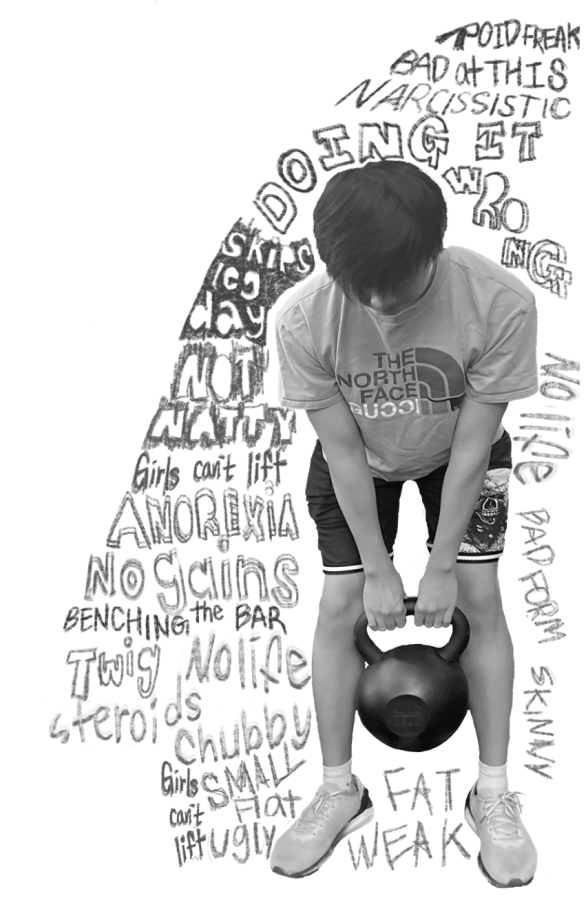

The rise of fitness-centered social media, the sheer number of local gyms and the popularity of school athletics have all contributed to the growth of fitness culture among Palo Alto teens. Some students workout together after school, turning their fitness ventures into social gatherings, while others create social media accounts to detail their progress and interact with online communities. On the surface, these habits seem purely beneficial: According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, working out can help prevent injuries, reduce stress and improve cardiovascular strength. The culture in the gym, however, is often much more toxic.

As gym-going becomes increasingly popular, it sets certain aesthetic standards. Those who don’t meet these expectations are classified as skinny and weak, or lazy and overweight. Furthermore, heading to the gym, especially with friends, can lead to unhealthy competition, harassment and bullying. These types of environments and experiences may lead to issues including insecurity, depression, steroid use, and, in extreme cases, various eating disorders, such as “reverse anorexia” — a belief that one’s body is too small or insufficiently muscular. Junior Samantha Snyder notes that this dysmorphia is often exacerbated by social media. “For other people, I’ve definitely seen (dysmorphia) as a huge source of insecurity and self-comparison, which is especially fueled by the influencers they see, who are super muscular and not actually natural,” she said.

Nutrition is often seen as the key to muscle growth and fitness. An intense focus on it, however, contributes to an unhealthy gym culture. As part of their personal fitness regimes, many students are highly cognizant of what they eat, contributing to obsessive behaviors around nutrition and more time and money spent on purchasing specific foods. Snyder, who started a personal fitness regimen several months ago, finds that unrealistic diets on social media only compound this issue. “It’s super hard to find that fine line between what you should be consuming for your own well-being and what others are recommending,” she said. “You have influencers telling you to go on carnivorous diets, you have trainers on YouTube telling you to go vegan to cut down your waist. It’s by far the most toxic aspect of gym culture.”

Toxic gym culture often prompts the overconsumption of protein to build muscle, which is shown to have damaging effects on the gastrointestinal system. This practice has been continually reinforced by the muscle-building myth that one should consume 2 grams of protein daily for each kilogram of one’s body weight. Medical centers such as the Mayo Clinic, however, suggest that individuals consume no more than 1.7 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight. Junior Aiden Chowdhury has seen the impacts these false recommendations can have on students. “Some people get super fixated on what they eat,” he said. “There’s always people perpetuating false myths. I’ve even heard stories about people trying to gain weight who literally fed themselves to the point of crying.”

Student gym culture also contributes to the use of steroids and supplements. Although steroids aren’t as commonly used among gym-going youth today, natural supplements of dubious safety — such as creatine, a biochemical compound that boosts muscle production, and ashwagandha, a root known to reduce stress — have gained popularity. Fitness content creators’ unrealistic appearances contribute to this trend. “(Social media) definitely adds to insecurity and self-comparison, especially since a lot of the big fitness influencers do not have ‘natural’ physiques because they are using chemicals,” Snyder said.

This dynamic provides false comfort regarding steroid or supplement use for teens, even if their parents or doctors dispel these myths. “I have seen certain people where it is safe to assume they are using steroids,” Snyder said. “It doesn’t affect me, but it does build a weird stigma around physique, because people will become super insecure comparing themselves to bodybuilders like Arnold Schwarzenegger, who are clearly athletically enhanced. It’s weird to know that people are willing to go that far and do that to their bodies, especially if they don’t know the effects or are ignoring them.”

Snyder added that the teenage tendency to seek false consensus contributes to questionable nutrition and supplement choices. “Teens will often look for information that agrees with them rather than information that is actually valid,” she said. “This includes information about side effects, which can be incredibly serious in some cases.”

The social aspect of frequenting the gym can, counterintuitively, harm students, who may begin to compare themselves to others when working out. Interactions with others at the gym may cause an individual to perceive themself as less fit or muscular compared to others, leading to self-esteem issues. This mindset can cause eating disorders and severe body dysmorphia.

Although various triggers exist within the local teen gym culture, they do not have to define a student’s gym-going experience. According to Snyder, focusing solely on one’s own health needs can help create a Palo Alto gym culture that gym-goers can thrive in. “As long as you can ignore all the toxic aspects and not take them into account, (going to the gym) is one of the healthiest things you can do for yourself,” she said.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Henry M. Gunn High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Senior Dan Honigstein is a section editor for In-Depth, The Oracle's newest section. Outside of the newsroom, he enjoys playing geography quizzes, discovering...